Tireless cultural activism has seen women artists from Africa rival their male counterparts on the world stage

In 1911, South African writer Olive Schreiner published Women and Labour, a landmark feminist book. Schreiner not only criticised the “wilful and unqualified” wrong of paying women less for doing equal work, but also noted how in the visual arts the gender bias saw “a mighty army of men, a million strong, employed in producing plastic art alone, both high and low” – everything from the decorative arts and illustrations through to paintings and sculptures. Much has changed in the ensuing century, and even more so in the past two decades. Tireless cultural activism has seen women artists from Africa rival their male counterparts on the world stage.

In the last year alone, whether it is at new museum openings in Cape Town or Marrakech, or at art biennales in Dakar or Lubumbashi, women artists from the continent have made a strong showing. Earlier this year in Germany, South African curator Gabi Ngcobo headed up the first all-black curatorial team for the Berlin Biennale, where her selection strongly favoured black women artists.

Painters like Ghanaian-British Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Nigerian-American Njideka Akunyili Crosby, Ethiopian-American Julie Mehretu and SA-Dutch Marlene Dumas are the most renowned African artists working internationally. That they choose to live and work in the global north is partly a reflection on the relative paucity of art patronage on the continent, South Africa aside. Things are changing, though, notably in Accra, Addis Ababa, Lagos and Marrakech, where burgeoning art scenes are enabling local talent to prosper.

This list reflects a new wave of female talent based in Africa. The list reveals some regional biases, which are unavoidable given South Africa’s outsize prominence. But, it also reveals the endurance of traditional techniques amidst a flourishing of new approaches.

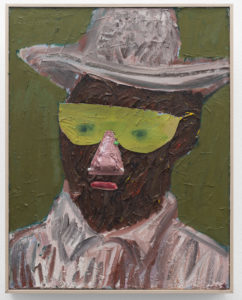

Georgina Gratrix

Durban-raised Gratrix (b. 1982, Mexico City) is best known for her vivid floral still lifes and portraits featuring richly textured surfaces. Blessed with a satirist’s sharp wit, her work is breezily mocking. Her portraits of chiefly white subjects are typically distorted, their facial features either exaggerated or misaligned in ways that flippantly misquote the earnest experiments of the Cubists. Rather than valorise her white subjects, and indeed the cultural traditions they represent, Gratrix wilfully troubles their puffed-up sense of self. Her gaudily coloured floral still lifes, a selection of which won her the 2018 Discovery Prize at Art Brussels in Belgium, mine a similar vein.

Dineo Seshee Bopape

Last year was a watershed moment for Dineo Bopape (b. 1981, Polokwane), a genre-bending artist whose practice encompasses drawing, painting, photography, filmmaking and the production of enigmatic sculptural installations. She won the $100,000 Future Generation Art Prize. Also in 2017, she staged live performances by the 20-member Polokwane Choral Society as part of her Standard Bank Young Artist Award. Despite their cryptic nature, the tumbledown aesthetics of her large-scale installations bear a ghostly resemblance to the informal structures created on the fringes and in the interstices of formal cities globally.

Elisabeth Efua Sutherland

In February, speaking at the 1–54 art fair in Marrakech, Elisabeth Efua Sutherland (b. 1991, Accra) spoke of how her interest in the performative arts was primed by her grandmother, Efua Theodora Sutherland, one of Ghana’s best-known playwrights and children’s authors. After returning to Ghana with a master’s degree in contemporary performance from Brunel University in London, in 2013, she debuted a production exploring an Ananse folktale at the annual Chale Wote Street Art Festival in Accra. Sutherland credits this spirited community event for introducing her to the city’s burgeoning alternative art scene. Although proficient with digital media, her first love is performance: “You can’t touch it. It’s an experience you have in a moment, and then it’s gone and you hold it in your memory.”

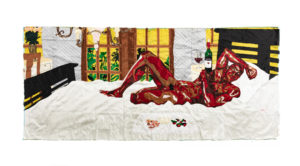

Billie Zangewa

Over the past two decades Billie Zangewa (b. 1973, Blantyre) has been making lustrous silk collages on irregularly shaped fabric grounds portraying narratives of urbanity, intimacy and selfhood. Inner-city Johannesburg was a prominent early subject. Raised in Botswana, Zangewa’s vision of her adopted hometown now exceeds the steel, glass and concrete infrastructure that first greets visitors; rather, what interests the artist is the city’s private social rituals and middle-class abundance. Her habit of orchestrating personal anecdote into pictorial form has, over time, seen Zangewa assemble a remarkable body of work that is unambiguously grounded in a “confessional feminism”, a term coined by critic Ginia Bellafante.

Photo: BLANK, Cape Town

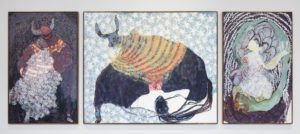

Portia Zvavahera

Zimbabwean Portia Zvavahera (b. 1985, Juru) is regarded as a leading exponent of Harare’s expressionist brand of figure painting. Zvavahera uses oil-based printing inks and oil bar to create limpid portraits of club-footed giants and spectral female figures decked in regal finery. She came to prominence in 2013 when she showed her work in the Zimbabwe Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. Zvavahera was shortly picked up by South African gallery Stevenson; in quick succession she won the 2013 Tollman Award for the Visual Arts and 2014 FNB Art Prize, both in South Africa. A devout Christian, Zvavahera says her paintings often reflect her life experiences. “I paint mostly painful moments,” she said. “It’s like a healing process.”