South Africa: boys’ lives are cut short

Traditional rituals at initiation schools clash with modern medicine

by Greg Nicolson

Last winter Sizwe (not his real name), 20 years old, went to an initiation school, a place where boys are circumcised as part of a traditional rite of passage to becoming responsible adults. “I wanted to go because in my culture a man is a man by going there,” he said of the school in South Africa’s Eastern Cape province.

Over 80,000 boys went to initiation schools in 2012, up from 30,000 in 2008, said Lechesa Tsenoli, traditional affairs minister, in Parliament this year. This rite of passage, also known as “going to the mountain”, usually takes place in rural areas far from any community. It is a secret ritual and initiates such as Sizwe and their families asked not to be named. During the initiation the boys will camp, sometimes for several weeks, under structures of branches and grass, but often under plastic sheeting. Their faces are smeared with red and white clay and their naked bodies are covered with only a blanket. The ritual starts with sacrificing an animal, often a sheep. Then their hair is shaved.

During the circumcision, a traditional surgeon pulls the foreskin over his thumb and severs it with a traditional knife, razor blade or pocketknife. Often no anaesthetic is used. The surgeon’s hands are often unwashed and ungloved. After the cut, the initiate’s foreskin is usually buried or tied to his blanket. Herbs and leaves are applied to the wound, which is then bandaged, sometimes so tightly that oxygen is cut off and an infection develops. A traditional attendant dresses the wounds, sometimes reusing the bandages on other boys.

A period of seclusion follows, lasting up to two months. For a week, the initiates cannot leave the camp or eat meat. Their fluid intake is limited and often they only survive on maize meal. The first week after circumcision may be marked by hunger, dehydration and seclusion. If an initiate falls ill, traditional doctors and nurses will treat him before he is taken to hospital.

“I wanted to be a real man,” said Sizwe, a student. But Sizwe may have lost his manhood in the process: “My penis got rotten because of the string that they used to tie it. They were bandaging it with the string so tightly until my penis got rotten.”

Little is known about male initiation schools in South Africa before the 17th century, but they have been popular throughout the colonial, apartheid and democratic eras, particularly in the Eastern Cape, Limpopo and Mpumalanga. The schools teach social responsibility, discipline, culture and self-respect.

About 30% of the world’s men are circumcised, according to a 2007 World Health Organisation report. Research shows that circumcision can reduce the risk of HIV infection by 48% to 60%, according to the report. This is crucial in South Africa where, according to the latest Statistics South Africa figures, 10% of the country’s population is HIV positive.

Religious cultures such as Judaism and sects of Islam circumcise boys with few complications, largely because trained practitioners perform the procedure at infancy rather than adolescence, which helps with healing. But in South Africa this tradition has recently been marred by deaths, mutilations and amputations.

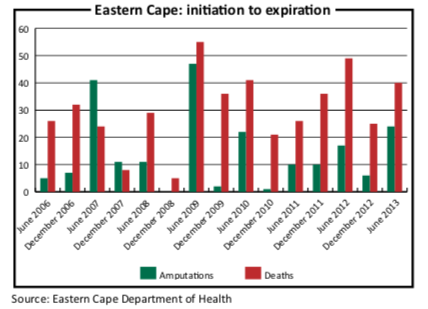

The availability of statistics varies. Mr Tsenoli, the traditional affairs minister said in August this year that 313 boys died in South Africa and 1,865 were injured between 2008 and 2012. According to police statistics and a report from doctors at Holy Cross Hospital in Flagstaff in the Eastern Cape, 754 initiates have died in this province since 1995. Thirty boys died in Mpumalanga this May, police said. In Limpopo, six boys died, taking the province’s tally to 40 fatalities since 2005, according to the provincial government. One initiate died at a school in the North West province this year. His body was found buried and burnt, police said.

“I feel like I’m less of a man,” said Sizwe, who lost part of his penis. “I feel like I’m useless and when I think of the future I won’t have—I won’t be able to make children in the natural way—I become very, very hurt and frustrated at the same time.” His father is worried he will commit suicide. “I regret ever going there,” Sizwe said quietly.

Holy Cross Hospital’s Dr Dingeman Rijken said that he has treated around 200 patients who have undergone this rite over three initiation seasons, two winters in June and one summer in December. He works with the Mpondo, one of the Nguni groups who live in the Eastern Cape’s Transkei area.

King Faku abolished the practice in the 1820s while the Mpondo were warring with the Zulu. Some say he stopped the rites because he thought circumcision weakened his troops. Other experts say he stopped the practice for many other reasons including the influence of Christianity. In any case, the tradition re-emerged during apartheid in the 1980s when local authorities pushed new forms of masculinity, according to Leslie Bank, a professor at South Africa’s University of Fort Hare.

As a result, many of the traditional surgeons and nurses who are now practising circumcision and treating patients are inexperienced and uneducated, with an inadequate knowledge of modern medicine and traditional practice. Regulating the schools is also difficult as local, provincial and national agencies fail to coordinate with traditional leaders to ensure that the schools meet regulations; the initiates are healthy, the traditional surgeons are experienced; and injured boys are taken to hospital before it is too late.

In the days after a circumcision, the wound needs to be dressed frequently. But some traditional nurses do not wash their hands as they go from boy to boy applying dressings, Dr Rijken said. Others reuse cotton bandages for wounds on boy after boy, rather than fresh bandages Often, the bandages are applied too tightly, sometimes to punish a boy or test his strength.

“That leads to basically all the problems that we see,” Dr Rijken said. “Because tissue that’s being deprived of oxygen is more vulnerable, you get infections much easier.” Infection and dead tissue lead to rotting. If the infection spreads, it creates sepsis, which can lead to organ failure and death.

Politics and culture clash when it comes to the initiation schools. The constitution protects these cultural practices and the national health ministry has the power to regulate their conditions, particularly regarding traditional circumcision. Much of the responsibility, however, falls on provincial authorities and traditional leaders. The Eastern Cape, Free State and Limpopo provinces have all passed laws to regulate the schools, while Mpumalanga is still debating its legislation.

The guidelines differ by province, but essentially the schools must first be registered. In Limpopo only a traditional leader may apply to the province’s traditional affairs department to hold a school. In Limpopo and the Eastern Cape, medical professionals must inspect the site and evaluate the traditional surgeon’s experience. Some provinces emphasise the need for community forums, composed of parents and concerned citizens, to approve the schools.

All provinces with legislation require a professional health worker to examine the initiate before he enrols to see if he is healthy and fit for circumcision. The aim of the screening is not to bar boys from attending but to alert the school officials to anything that may require special attention or treatment such as HIV, asthma or epilepsy. Parents must give their consent and schools must allow random government inspections.

This ideal is rarely the reality, however. Located in rural areas and with few government officials checking for compliance, many schools simply do not register. Sometimes traditional leaders have approved the schools, but have done so without consulting the provincial departments of traditional affairs or health. Penalties for performing a circumcision without meeting provincial guidelines include a fine of 10,000 rand (about $1,000) in the Eastern Cape and ten years imprisonment. There are also news reports of schools kidnapping boys, but often it is later found that the young men decided to attend without telling their parents.

Parents and their sons feel strong societal pressure to uphold this initiation ritual, which has become a lucrative business. Often they overlook whether a school is registered and many illegal or unregistered schools bypass official procedures. “The mushrooming of initiation schools is seen every single day in [the] Eastern Cape,” said Aaron Motsoaledi, South Africa’s health minister in June. “Hooligans, tsotsis [gangsters] take advantage and prey on this custom.”

Some initiates, desperate to be a man, lie about their age or skip the medical examination because they are scared of missing out on the ritual and not becoming a man. A national age restriction does not exist, but in the Eastern Cape boys must be at least 16 years old, 12 in Limpopo and 18 in both the Free State and Western Cape.

Confusion about who governs and regulates these schools make them much more difficult to supervise. Schools are often located in difficult-to-reach areas, making inspections a challenge, said Nkululeko Nxesi, part of a joint private and government monitoring team in the Eastern Cape. During the 2013 winter initiation season, Mr Nxesi said that he witnessed traditional surgeons who were drunk and violent and initiates who were dehydrated and hungry. When he notified police about an abusive school, the culprits were arrested but released the next day. “They get away with murder, literally,” he said.

Jaxa (not her real name), 38, unemployed, got a phone call in June this year that informed her that her son was in hospital. The last time she had seen him he had been on his way to an initiation school outside Flagstaff. She went to the hospital and saw her son’s rotting penis. The blood and pus had dried and her son’s penis was stuck to his pants. “I wanted him to go [to the initiation school] as everyone goes and it is part of our culture. His friends and neighbours went, so he also enrolled,” Jaxa said, sobbing.

Although her 17-year-old son lived, his penis is now mutilated. “He still faces abuse even today from the boys, men, who went to the mountain,” Jaxa said. “They once beat him so hard he had to be admitted to hospital. He is called names because he is not a man; he never made it in the mountain,” she cried, explaining that her son did not finish the school and cannot be called a man. “We are left with [a medical] debt. He was just following the pressures of being a man.”

Over the years there have been only a handful of arrests and fewer prosecutions for the deaths, mutilations and amputations. Asked for comment, police spokespeople could not explain the lack of justice. Mr Nxesi’s organisation, the Community Development Foundation for South Africa, an NGO that mentors rural development organisations, wants to compel traditional leaders to act responsibly. In October it plans to lodge a class-action lawsuit on behalf of victims of slipshod circumcisions. If those responsible are not sent to jail, forcing them to provide compensation may make others wary of holding illegal schools and botching circumcisions, he reasons.

A coordinated effort from local, provincial, national government and trad- itional leaders is crucial to prevent these failed and fatal circumcisions. After the deaths in the recent season government and traditional leaders met and agreed to establish national guidelines to regulate the schools and their management, the age of initiates, nutrition, guardian consent, fees, medical emergency plans, and the role of traditional surgeons and caregivers.

The national health department said it would launch a new plan in October, ahead of the December initiation season. The new plan (still not revealed before going to press) will likely promote the practice of medical circumcision, which would place professional doctors and nurses at the initiation sites.

Healthcare professionals say their presence would almost completely eliminate fatalities and morbidity. But initiation is a rite shrouded in secrecy and many traditional leaders are opposed to outsiders. Others are concerned that their traditional practice will be eroded if combined with modern medicine.

In Pondoland in the Eastern Cape where Dr Rijken has been treating the circumcised wounded, traditional authorities want to centralise the schools. Instead of the current 69 sites, they want to li- mit the number to seven, one per chief. “That’s much easier to monitor,” Dr Rijken said. “Now, it’s just impossible to monitor all the schools and they only call us by the time that the boys actually are already dead.”

These responses will be tested in the December initiation season. Mr Nxesi and others are confident there will be fewer deaths and amputations this year because Mr Motsoaledi promised more funding in June.

Dr Rijken, however, is a bit more sceptical. He has not seen any improvement. “In our experience it’s absolutely not getting better. As far as I’m concerned it’s only getting worse,” he said. In any case, it is too late for Sizwe, Jaxa and her son.