West Africa’s airports: about to take off

Billions of dollars are being spent on new terminals and renovations as investment and tourism rise

by Afua Hirsch

Africa’s airports need an upgrade. Though three of the world’s best airports— ranking higher than any airports in the US—are in South Africa, others on the continent are terminally ill.

Skytrax, a research company which surveys millions of passengers, listed South Africa’s Cape Town International Airport at 22nd best, Durban’s King Shaka International at 26, and Johannesburg’s O.R. Tambo International at 28 on its 2013 list of the world’s 100 best airports.

No other airports in Africa appeared on this list, supporting claims that the continent has neglected aviation spending. But soaring economies in countries such as Ghana, Ethiopia, Nigeria and the Democratic Republic of Congo have led African airlines to post annual growth of 11.2% in international passengers, according to a June 2013 report from the International Air Transport

Association, an industry club.

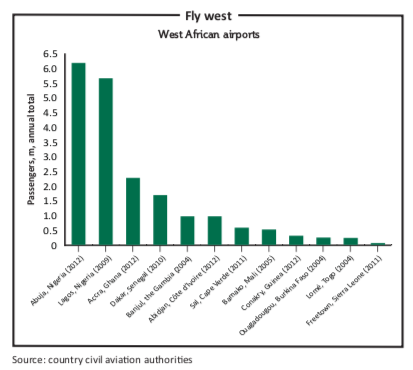

West Africa, particularly notorious for its poor transport links and decaying airport facilities, is frantically trying to catch up. None of its ranked airports are on Skytrax’s top ten list of African air- ports. Across the Gulf of Guinea and the Sahel, billions of dollars are being spent on new sites and terminals and the renovation of existing ones as the region attempts to accommodate rising investment and tourism, and cash in on potential passenger growth.

There is a lot of new construction in West African airports, and it is badly needed,” said Chloe Grant, an aviation consultant who specialises on West African aviation. “These airports have fallen way behind the times in all respects—from runways to safety and perimeter fences. Everyone sees that the economy in these countries is growing, and there are more people coming in, and suddenly the lack of investment in airports over the years is catching up with them.”

Burkina Faso is one of several West African countries trying to keep pace. Its current airport in the capital city of Ouagadougou has outgrown its infrastructure. Between 2005 and 2009, air passenger traffic at Ouagadougou grew at an average annual rate of 7.2%, reaching about 349,000 in 2009, according to a 2011 World Bank report. Based on conservative estimates, passenger traffic is projected to reach about 850,000 by 2025. The existing airport is expected to run out of terminal capacity by 2016–2017. The construction of a new airport is “essential to make Burkina Faso a sub-regional aviation hub and to develop its largely untapped tourism potential”, the report said.

“Airports must respond to economic needs, and this is something that requires vision,” said Moumouni Dieguimde, former director general of Burkina Faso Civil Aviation and now the country’s representative on the UN’s International Civil Aviation Organisation Council. “At the moment, these needs are growing. We have an expansion in traffic, our current airport is located right at the centre of the capital, and our country is located in the middle of the region. That gives us a comparative advantage when it comes to traffic between other African capitals and in transport to tourist sites.”

Travelling in Africa can be gruelling and time- consuming, often requiring several stopovers. “At the moment, to get from one African country to another, it’s often easier to travel through Europe rather than to connect to a neighbouring country,” Mr Dieguimde added. “That creates an opportunity, and these are all reasons why it makes sense to have our airport expanded.”

To meet this growing demand, Burkina Faso is building a brand new airport 40km north- east of Ouagadougou, an ambitious project that begins this year and is expected to be completed in 2017. The new Donsin International Airport, named after the tiny village where it is being constructed, is estimated to cost at least $450m, with 20 funders participating, including the Kuwait Fund for Arab Economic Development, the World Bank and a swathe of other African, Arab and European investors.

Like many new airport projects, Donsin is being funded through a public- private partnership (PPP), with private sector investors likely to hold a controlling stake. Despite the benefits of entering into PPPs, some African countries were choosing speed over long-term considerations when it comes to sourcing finance, industry figures said.

“PPPs are a good model for long-term airport projects,” said Carla Rooseboom, senior manager in corporate finance at Deloitte in South Africa. “They work for airports which have good potential in terms of passenger numbers or freight and can find funding quite easily—the World Bank and commercial lenders are keen to fund those sort of airport projects too. But a lot of African countries are still establishing their PPP legislation. And even when the legislation is in place, it is unlikely that you can really procure a PPP in less than 18 months on a fairly complicated project,” Ms Rooseboom added. “If there is a sense of urgency, [African countries] tend to go for foreign direct investment or Chinese funding.”

That is the case in Sierra Leone: The government has announced that the China Railway International Company, a major player in infrastructure construction in West Africa, will build a new $200m international airport, with financing from China’s Export-Import Bank.

The new airport will replace Lungi Airport in Freetown, the country’s capital. Reachable only by boat or by a four-hour drive, Lungi Airport is one of the region’s least practical aviation arrangements. The government hopes the new airport will attract coveted direct flights from US airlines, none of which currently fly to the country.

Some observers are concerned, however, about the long-term quality of Chinese construction projects. “It’s early days to judge the quality of the Chinese-built airports,” Ms Rooseboom said. The benefit of a PPP is that the investor will consider carefully the long-term operation of the airport and make sure it operates as efficiently as possible. A PPP investor “is going to put a lot of thought into the design and making sure it fits with the operational needs”, she added. “If you get a Chinese company to build an airport as quickly as possible, there is going to be a lot less thought that goes into building it.”

Investing in new airports in West Africa is not without risk. Take Senegal’s Blaise Diagne International Airport—named after the former mayor of Dakar and the first black African to be elected to the French parliament in 1914. Its construction began in 2007, was meant to be completed in 2009 and is still not finished. Saudi Arabia’s Binladen Group, owned by the estranged family of Osama bin Laden, is building the $450m project, which has been besieged by delays. It is now expected to be completed in 2014, according to the African Development Bank, which helped arrange the financing.

But the challenges of constructing airports have not dampened interest. Conferences and donor forums on airport and aviation infrastructure are springing up, with increasing levels of interest.

“We have got quite a lot of big companies on board as sponsors for our event and a lot of high quality enquiries,” said Erena Christofides from IQPC South Africa, which is organising the Modern Airports Africa 2013 conference in Nairobi this November. “There is a lot of interest in African airports, airport reviews and airspace at the moment.” Nairobi’s Jomo Kenyatta International Airport—a major aviation hub for East Africa—was brought to a standstill in August as a fire gutted its arrivals terminal. No official cost has yet been given for the repairs but the airport, built in the 1970s, was badly in need of an upgrade. When the fire broke out, a five-year multimillion-dollar expansion had already begun.

Outdated and crumbling airports are not the only factors grounding West African countries from realising their potential in business, tourism and transit travel. African civil aviation ministers from 44 countries met in Yamoussoukro, Côte d’Ivoire, in 1999 and signed an agreement to open up the region’s air spaces after decades of protectionism designed to protect national carriers. But this accord has still not been fully implemented. “One of the problems for aviation in West Africa has been that it hasn’t been liberal,” said Catherine Hoffman, director of economic regulation and business development at the Ghana Civil Aviation Authority.

There have been limits on the number of times airlines can fly into Ghana and the kind of aircraft they can use. “But that has changed, especially with Ghana, if you are a member of the Yamoussoukro agreement and you meet our safety regulations, we will let you operate in Ghana, we will give you the route,” she added. “In my opinion this has helped Ghana to become an aviation hub. People want to transit in Accra rather than in Lagos, even though Lagos has more facilities, because of our liberalisation and also because of safety concerns.”

Ghana is trying to further advance its status as an aviation hub with the construction of a new international airport in Tamale, a large city 600km north of Accra, the country’s capital. The airport, initially built as an operational base for troops during World War II, is being expanded following a $100m commercial agreement with Queiroz Galvão, a Brazilian construction company.

“Interest by domestic carriers to do sub-regional flights is growing and the rapid growth in domestic traffic is expected to expand into the sub-region,” said John Amedior, deputy managing director at Ghana Airports Company Limited. “Patrons of Haj [the pilgrimage to Saudi Arabia] and potential exporters of fresh agricultural produce will definitely solicit the services of airlines. Furthermore, the availability of the airport is expected to serve as a marketing tool to further develop the international routes.”

While everyone agrees that building new airports is necessary, is it enough to boost economic growth in the region? “At the moment I’m afraid to say it’s just a trend that everybody in the region thinks of a new airport,” Mr Dieguimde said. “But in a region that is poor, for effective poverty reduction, you need to sustain that with other final services and goods—like tourism, training centres, free zones. And you need coordination and teamwork with other countries. Just building new airports is not enough.”