New tech tools for hacks, whistleblowers and activists

by Adam Clayton Powell III

Armed with a mobile phone, anyone can share news stories, video footage and radio broadcasts with the world. Often called citizen journalists, these mostly untrained volunteer newscasters, activists and whistleblowers can take advantage of powerful new technologies, many created in Africa, to collect and distribute their reports. Many of these new digital tools are inexpensive or even free. Often, they do not require internet access.

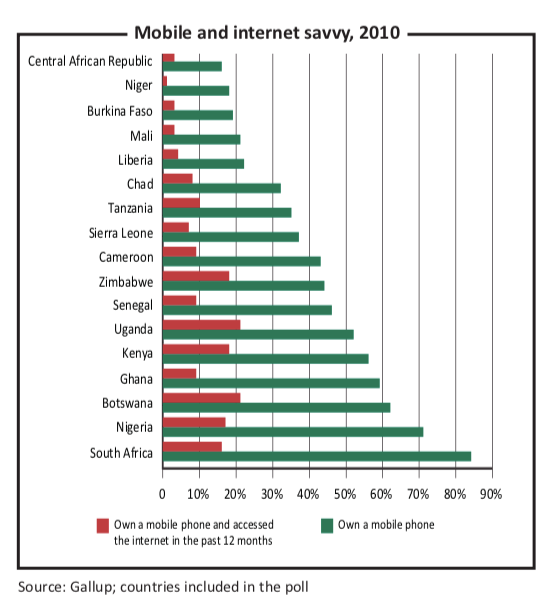

The ubiquitous mobile telephone makes this all possible. According to a multi-country 2012 Gallup survey, half of all Africans surveyed living on less than $1 a day had access to a mobile phone, that is they either owned one or were able to borrow one from a relative, friend or neighbour.

Absolute majorities of Africans living on less than one dollar a day owned their own cellphones in countries including Botswana, Kenya, Nigeria and Zambia. Together with those who reported they had access to a relative’s or friend’s mobile, cellphone penetration exceeded 80% of poor Africans in countries including Botswana, Kenya and Zambia. There was only one country — Mali — where a majority of those living on less than one dollar a day did not have access to a portable handset.

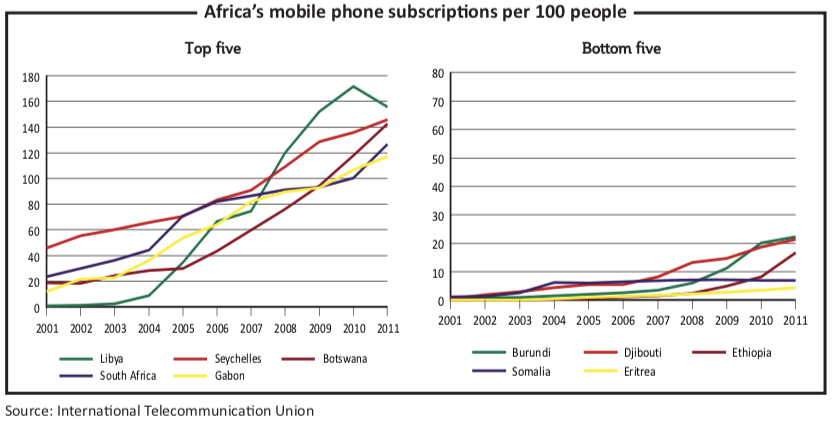

More and more Africans are expected to use mobile phones. Alcatel Lucent is projecting a 60% increase in the number of mobiles on the continent, from 500 million in 2012 to 800 million in 2015, according to an Inter Press Service report. Of these, 80% will be internet-enabled. By comparison, just 12 years ago there were only five million mobile telephones in all of Africa. This means activists and citizen journalists can distribute reports without the need for radio, newspapers or television.

Meanwhile, the power of inexpensive, low-end cellphones has increased, making possible access to tools that only a decade or two ago would have been considered science fiction.

Consider e-mail: now anyone with a mobile has access to e-mail messaging, even if their telephones do not have internet access. For example, Gmail SMS from Google is a free e-mail service that runs on “dumb” mobile phones with no internet access. Users can send and receive e-mail in the form of SMS messages on low-end phones that are not equipped with wifi or third-generation (3G) internet capability.

SMS is another powerful technology. In Kenya, anyone with a cellphone can use Hatari, a tool that lets members of the public report bribes and corruption by e-mail, text or tweet. Another is M-Maji, which provides real-time information about clean water — prices, suppliers and availability — to urban slum dwellers on cellphones.

Mimiboard, a virtual noticeboard, is another rapidly spreading innovation. It won the most votes at last year’s Open Innovation Africa Summit. Using the web or SMS, users can post events and information about social and political issues, sports and entertainment in their communities.

Mimiboards have already attracted citizen journalists and activists who may not be able to operate openly. For example, The Zimbabwean, a digital news provider published by dissidents in exile, has already launched Mimiboards for several local regions, according to its website.

Freedom Fone, another platform created in Zimbabwe, allows citizen reporters to use phones to file audio reports on events as they happen. During a breaking news story such as an election, or a crisis such as a flood, anyone can dial a number, follow voice menu prompts and provide updates, leave voice messages to receive field reports or use polls for focused feedback.

Many non-governmental organisations (NGOs) are already using these tools. “We use mobiles for new media campaigns for public awareness,” Sam du Pont, former programme officer for internet freedom at Freedom House, a US NGO with regional offices in Africa, told me in an interview. “The tools we use are predominantly mobile-based. The groups we work with use the web, e-mail, and social media to certain degrees. But for any communication for mass scale, we use SMS.”

NGOs and international media organisations also provide training to citizen journalists in the use of these tech tools. Voice of America (VOA) has trained about 100 correspondents in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) to use low-end inexpensive mobile phones to send stories, photos and even videos directly to Facebook and Twitter. The head of the network’s French to Africa Service said the contributions of the citizen reporters supplement the work of professional broadcasters.

For the more ambitious (and technically-skilled) citizen journalist who has a higher-end smartphone, there is the personal radio station, which can now be started for little or no money. Journalism.co.uk, an online publishing company, recently posted a guide that explains how to create a radio station using Airtime, a free or paid-for radio management application. The radio station runs from a web browser and includes the option of streaming live reports from a smartphone.

An ambitious citizen journalist can combine these tech tools with SMS and audio to create news stories aimed at anyone with a cellphone. Unlike most of the world that is accustomed to the 15-second sound bite, Africans have embraced mobile- delivered audio in ways that are quite different from the rest of the world.

“Africans are listening to their phones for 20-minute programmes,” Steven Ferri, VOA’s Africa web managing editor, told me in an interview. “No one in America would do this.”

That is the good news. The bad news is that autocratic governments have learned how to use new technologies to locate citizen journalists and subject them to harassment and worse.

“Mobile is a scary platform,” Freedom House’s du Pont said. Cellphones “are one of the least secure technologies we have for secure communications. Any SMS that bounces off the [cellphone] tower can be read by the mobile operator — but also by anybody sitting beneath the tower with a thousand dollar piece of equipment.”

The broader danger was described concisely in the 2011 annual report of Amnesty International: “Technology will serve the purposes of those who control it — whether their goal is the promotion of rights or the undermining of rights. We must be mindful that in a world of asymmetric power, the ability of governments and other institutional actors to abuse and exploit technology will always be superior to the grassroots activists, the beleaguered human rights advocate, the intrepid whistleblower and the individual whose sense of justice demands that they be able to seek information or describe and document an injustice through these technologies.”