A voluntary programme to promote greater transparency in oil, gas and mining may have entrenched devious ways of concealing bribes and other forms of corruption. Mark Thomas looks at this initiative and shows how corrupt governments and private companies circumvent it.

Africa is teeming with oil, diamonds, gas, platinum, gold and other minerals. Despite this wealth, it remains the world’s poorest continent. Nearly half of sub-Saharan Africa’s population live in countries that are rich in these natural resources, according to the World Bank. These countries account for some 70% of Africa’s gross domestic product (GDP) and receive the overwhelming bulk of foreign direct investment (FDI) into the continent. Commodity prices have risen about 75% in real terms since 2000.

Despite these surging revenues, only a tiny elite of Africa’s citizens and many foreign firms are reaping the benefits. Too many of these resource-wealthy countries remain poorly governed and wracked by corruption and conflict.

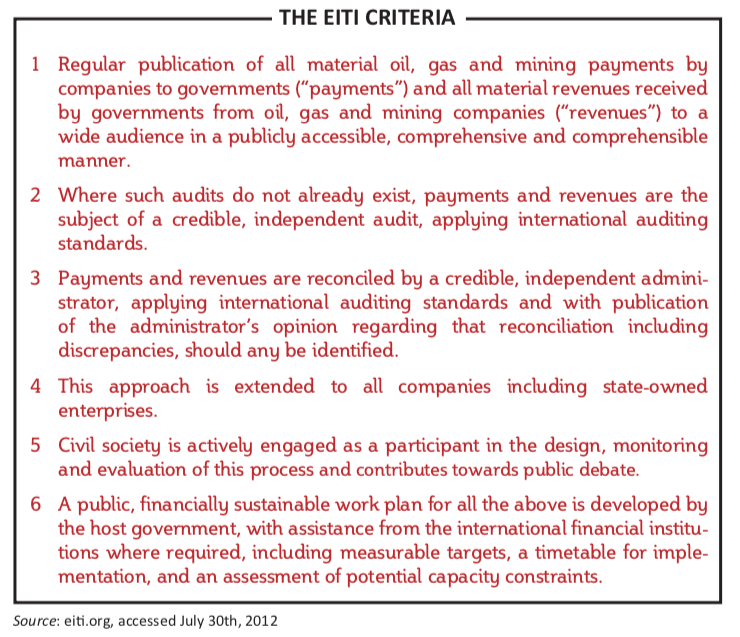

The goal of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) is to promote better use of mineral revenues for economic growth and poverty alleviation through increased transparency and accountability. It encourages governments and companies to publish their revenues and payments and then submit them to independent auditing.

But ten years after its launch in Johannesburg at the World Summit for Sustainable Development, it is now apparent that the initiative lacks teeth. Demanding transparency from governments and corporations in the extractive industry is not enough to ensure good governance, economic growth and more equitable distribution of wealth. Governments and private companies still resort to timeworn and ingenious ways of hiding their buyoffs and kickbacks.

“A mere demand for transparency is not necessarily a check for acts of bribery that happen in the industries,” said Oladayo Olaide, a policy analyst with the Open Society Initiative for West Africa. “Corporations and political players involved in the underhand deals have perfected the means of hiding the proceeds of such acts beyond the unqualified eyes of the public… How do we assess the ‘cost build-ups’ and ‘in- kind’ payments? Most governments lack the capacity to query figures and fees that the involved corporations present.”

The EITI is a voluntary programme. Countries that sign up commit to allowing regular audits and reconciliations to be conducted by a local group that includes representatives from government, private companies and civil society. Of the 36 countries which have signed up, 21 are from Africa.

Its grading system awards two marks: pass and fail. There are no punitive or other measures to ensure that identified discrepancies are rectified conclusively. The most the EITI international secretariat, based in Oslo, Norway, can do is plead with the offending governments. So far, 14 countries have attained compliance status, including seven in Africa.

Nigeria signed up for the EITI in 1999, following demands for economic reforms by its international trading partners—Britain, the United States and several members of the Paris and London Clubs, two informal groups of private creditors from some of the world’s biggest economies.

Despite achieving full-compliance status, Nigeria has not addressed the discrepancies revealed by the latest reconciliation conducted by Hart Nurse Limited and SS Afemikhe & Co., the independent auditors hired by a local group of government, company and civil society representatives.

The extractive industry is notorious for corruption, which remains entrenched despite the EITI. Oil, gas and mining companies are linked infamously to human rights violations such as in the Chiadzwa fields in Zimbabwe, kidnappings in the Niger Delta, conflict in the Congo, murder and environmental abuse elsewhere.

Uncovering fraud, bribery, money laundering, tax cheating and other corrupt practices is tricky. The EITI validates compliance on a country-by-country basis. This allows multinationals to hide under- the-table payments in other countries that may serve as tax havens.

“By splitting the analysis between countries—thus missing the transnational element and failing to scrutinise rich countries’ role—one too easily reaches the conclusion that they (in Africa) are corrupt, while we (in the West) are clean,” said Richard Murphy, director of Tax Research LLP, a United Kingdom accounting consultancy, and Nicholas Shaxson, an associate fellow at Chatham House, a London-based think tank, in an editorial published in 2007 in the Financial Times.

Shady deals may come to light only when a losing contender reveals an earlier demand for a kickback or when an employee with knowledge of the fraudulent transactions decides to spill the beans. Often illicit payments can be found in the balance books, hidden under such rubrics as “cost build-up” and “in-kind payments.” Government watchdog groups lack the technical expertise and auditors for private companies cannot be relied on to query such payments.

Until the September 11th 2001 attacks in New York City, corporations could vie for lucrative concessions and shroud their payoffs into the offshore secret accounts of politicians and other key players. But more open banking practices instituted worldwide in the fight against terrorism have made secret bank accounts difficult to hide.

Companies and governments are now resorting to “in-kind payments” to disguise these backhanders. For instance, leasing office space from an individual with the right political connections at a rate higher than the prevailing market price is a common way of making an in-kind payment.

Another practice is to recruit relatives or friends of an influential and politically- connected individual and retain them on payrolls as “facilitators” or “consultants” without clearly-defined responsibilities. Inflating costs for replacing equipment and parts is another fraudulent practice.

Companies use their subsidiaries as another vehicle for hiding bribes under the heading of “cost build-up”. Invoices to subsidiaries are also disguised as consultancy services.

Since taxes are often based on profits, companies may under-declare to save on these levies. By billing a subsidiary, sometimes with highly inflated invoices, the multinationals reduce their tax obligations to the host country.

Most multinationals have perfected the art of exaggerating their real overheads to tax authorities, Mr Olaide says. “An oil company would document the need for a particular ‘proprietary item’, which can only be supplied by one of its numerous subsidiaries at a self-determined price. It’s not like a water or wine glass where one can go to the market and establish the average going price.”

Tax authorities and other govern- ment agencies frequently lack the technical knowledge needed to verify the true value of invoiced items. “Even the EITI, as narrow as its objectives are, has not been able to address the issue of bloated costing. It only looks at the final products—the information that has been provided by the executives of the extracting corporations. It does not go out to verify the validity of those cost items,” Mr Olaide adds.

In other instances, gold and diamonds are polished or cut in a third country which has a lower corporate tax. The company declares a lower value for the raw product and therefore pays a lower tax.

Many African countries lack the capacity to assess and qualify the costs involved in the industries and surrender the responsibility to experts provided by the World Bank, the United Nations, the International Monetary Fund as well as various international oil companies.

Unfortunately, these external experts rarely prioritise the interests of the local communities, particularly during contract negotiations. Once the contracts are signed, these countries lack the expertise to evaluate the exact quantities of the resources extracted and have to accept whatever value the corporations declare.

Nigeria is Africa’s largest oil producer and has decades of experience. But it still relies on oil companies to determine the volume of oil produced and shipped out of its territory.

So if the EITI provides only a superficial clean bill of health, should it be maintained?

Some information is better than nothing, Mr Olaide says. “For decades, extractive industries were seen as an exclusive preserve of governments who entered into secret contracts with mining, oil and gas exploration companies without any involvement of communities or civil societies,” he says. “Now, at least with the limited publication of information, the civil societies as well as the citizens are slightly armed to an extent that they are able to interrogate details of contracts entered into by their governments.”

Financial impropriety in Africa, often documented as the “cost of doing business in Africa”, affects consuming countries with higher prices and producing countries with lower tax revenues. To remedy these problems, several countries are in the process of strengthening their anti-corruption laws, such as the United States’ Dodd-Frank act and the United Kingdom’s Bribery Act. Mr Olaide reckons that civil society organisations could use the information provided from the EITI audits to seek legal redress using these new laws.