Transforming raw materials into manufactured goods

African countries can turn their natural resources from a bane into a boon

Africa, blessed with many minerals and other natural resources, has often fallen prey to the resource curse. This disease comes in two forms: revenues from natural resources push up a country’s currency exchange rate and depress other sectors, particularly manufacturing; and/or governing politicians become “rent-seekers”, seizing control of these assets and using the income to stifle opposition to their rule.

Despite Africa’s wealth in oil, gold, chromium, platinum and other minerals, very little manufacturing takes place on the continent. Rent-seeking and corruption have created powerful elites that block diversification and inclusive growth. Too many leaders and their cronies use resource income for personal enrichment at the expense of development. For example, about 80% of Nigeria’s oil wealth accrues to 1% of the population while the percentage of people living on less than a dollar a day has increased from just over 27% in 1970 to about 75%, wrote Greg Mills in his 2010 book called “Why Africa is Poor”.

Resource rents, however, can be harnessed to drive industrialisation in Africa, in four steps.

First, create a mutually advantageous environment for governments and private firms for mineral discovery, investments and extraction. Too often governments lack the expertise to extract the resources and the political will to share the income equitably with their citizens. On the other hand, mining companies, like most businesses, are interested in maximising profits.

These divergent interests can be tamed to meet the needs of both in the interest of the country. Transparency in public tendering and competitive bidding would go a long way in providing governments with better financial and other returns. In auctioning off contracts, governments can choose firms that offer the best terms, particularly in creating jobs or programmes that benefit communities. Policymakers can also adopt and enforce strict regulations that discourage opportunistic speculators from buying and selling exploration licences. Governments must give mineral rights only to firms that will invest and develop the mineral plots.

Second, tailor a tax regime to make adjustments for costs and profits. Paul Collier and Tony Venables, Oxford University economists and authors of “Plundered Nations”, compared the cost of copper mining in Zambia and Chile. According to their analysis, Zambia, as the higher-cost producer, is best served by a flexible tax regime that can be adjusted against copper price fluctuations. This would protect Zambian copper from becoming too expensive and thus safeguard its global exports.

The ideal tax regime encourages long-term exploration beyond an initial contract. Botswana, for instance, has succeeded in increasing private-sector investment through its 19.5% income tax on profit, which is significantly lower than the average sub-Saharan rate of 68%, according to the 2012 African Economic Outlook, a report produced by the UN, the African Development Bank and the OECD, an intergovernmental think-tank based in Paris.

Benefits to the state must also be maximised during an asset’s limited life span, particularly at its early stages when it is still highly profitable. In the past, companies paid taxes only after they had recouped their investment, usually when extraction and profits were low. The 1980s structural adjustment programmes gave private investors very lenient terms that saw “the burden of tax [structured] in such a way that little tax was paid until the invested capital was recovered”, according to a 2011 report by the UN Economic Commission for Africa.

This meant that the state collected significantly lower taxes because the profits were lower. Governments could have collected more had the agreements been structured to collect taxes when the mines were most profitable, usually when extraction was at its highest in the early stages. Ghana, for instance, has succeeded in receiving early revenue from its oil and gas royalty taxes.

A tax regime can also ring-fence projects and limit the extent to which private firms can receive tax deductions from one activity against another, according to a report written by Nana Adjoa Hackman, an oil and gas expert, for the Danquah Institute, a Ghanaian research centre.

Third, adopt strategic savings and investment plans in infrastructure and technology, both crucial for industrialisation and growth.

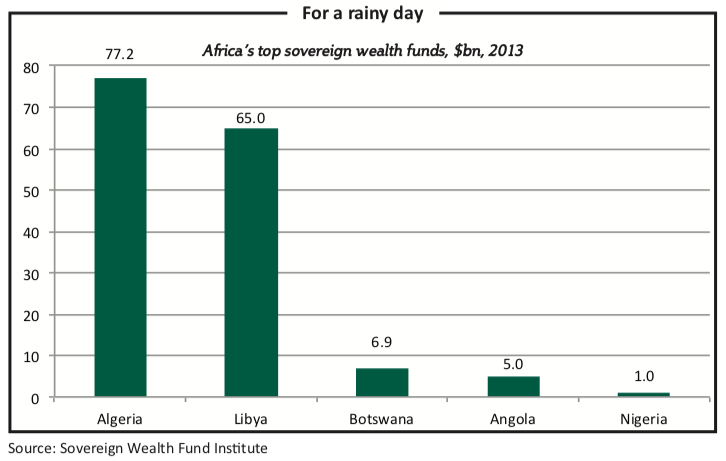

Resource-rich countries often pool their profits from oil, gas or minerals into sovereign wealth funds (SWFs), government or state-run accounts. Africa has nine SWFs, according to the Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute, a US-based think-tank. Of the largest five, four are based on oil and gas, while Botswana’s is based on diamonds and other resources.

SWF benefits are short- and long-term. In the short term, countries use these state accounts to smooth expenditure when commodity prices are bumpy, which could negatively affect expenditure planning. In the long term, SWFs can safeguard declining revenues as resources run out. SWF proceeds can also be spent on investing in sectors that spur diversification.

SWFs can ring-fence revenues from political interference through adherence to international conventions such as the Santiago Principles, a set of 24 accounting and investment guidelines emphasising transparency that was adopted by 26 SWFs around the world in October 2008.

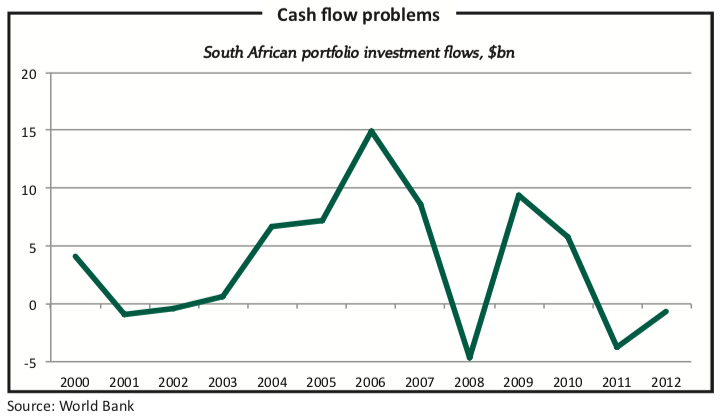

SWFs can also curb risky overreliance on foreign capital. Stops or reversals in capital flows have been frequent in South Africa since the 2008 recession and have crippled the country’s job-creating potential, according to this author’s analysis. Capital flows affect the currency’s stability, which also affects export prices. In the manufacturing sector, when the price of tradable goods is volatile, few jobs will be created as companies are unlikely to take on additional costs in the face of uncertain profits.

South Africa’s 2009 fourth-quarter decline in GDP of 6.4% was a direct result of capital flow reversals experienced by the Johannesburg Stock Exchange six months before, according to a 2012 report by University of the Witwatersrand economists Rex McKenzie and Nicolas Pons-Vignon.

The fourth step towards resource-led development is through diversification. This requires creating strong links between core commodity sectors and the rest of the economy. A country’s industrial base can be strengthened through backward linkages such as manufacturing and purchasing mining equipment to extract the resource; and forward links through mineral beneficiation and value addition, such as creating jewellery, after the commodity has surfaced.

De Beers and Debswana, Botswana’s state-owned diamond company, renegotiated a contract in 2011 that called for moving the Diamond Trading Centre (DTC) from London to Gaborone, Botswana’s capital. The DTC move will see the value of Botswana’s diamond sales increase from roughly $500m to about $5.5 billion, said Varda Shine, De Beers diamond trading global head, in a 2012 article in Mining Weekly.

The DTC has also created about 160 new specialised jobs and is expected to create many more over the next three to five years, according to industry insiders. The DTC is a major step forward in creating a regional diamond-trading hub and diversifying Botswana’s economy. It is an example of a forward linkage that will yield long-term returns as it develops local workers’ skills and technical expertise.

Other African countries need to follow Botswana’s example, and renegotiate or create new agreements with foreign investors to secure terms more favourable to their own economies and people.

Many African countries today are in an excellent position to reduce poverty, inequality and unemployment. With the dramatic decline in diseases associated with malnutrition and recent positive developments in combating HIV/AIDS and malaria, African populations are healthier today than ever. Through broad democratisation, political accountability on the continent is at its highest. In addition, the continent boasts unparalleled economic growth rates. Finally, the global community seems to have an insatiable appetite for Africa’s commodities.

Dynamic policies that define a new industrial landscape could lead Africa into a new era of inclusive growth and prosperity. This requires transforming the commodity boom from a curse into a blessing.