Tunisia: how to kick-start a divided economy

The north African country should link its coast and interior by creating quality jobs for its well-educated youth

Tunisia’s economic history is a tale of two territories: its coastal cities export mostly to Europe across the Mediterranean Sea; its farms on the dry central plains grow food for the local market.

This split narrative led to the birth of the Arab spring in December 2010. A street vendor, 26-year-old Mohammed Bouazizi, set himself on fire in Tunisia’s central Sidi Bouzid governorate. His act was meant to draw attention to the interior’s high unemployment, especially among youth and college graduates who have few connections to the coastal cities. It also sparked a wave of protests that swept across North Africa.

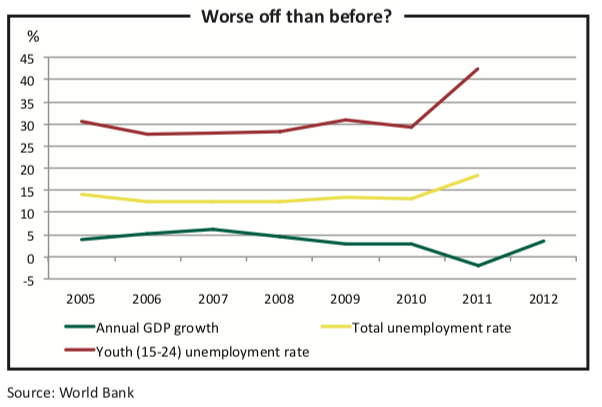

Tunisia’s economy today, however, provides fewer jobs than it did before the revolution. Although GDP growth has recovered slightly from its shock in 2011, unemployment is markedly higher, rising to 18.3%

in 2011, according to the latest World Bank figures. But not all is bleak: former President Zine al-Abidine

Ben Ali’s era of corruption and cronyism is over.

Tunisia’s well-educated and youthful population brightens the prospects for building a strong and inclusive economy.

For decades before the revolution, the Tunisian government practised central economic planning as part of its state-sponsored industrialisation policy. It dictated private-sector growth, largely to strengthen political control and corruption. The regime favoured the lucrative export-oriented, Europe- facing firms based in Tunisia’s coastal cities, especially manufacturing firms such as the Tunisian Compagnie des Phosphates de Gafsa and the Austrian oil and gas giant OMV.

Simultaneously, the government kept a lid on social unrest by subsidising staple products such as food and fuel. These subsidies, however, made business extremely difficult for domestic producers, particularly of olives, grains, tomatoes and canned goods, based mostly in the interior. Despite their significantly lower costs, local growers could barely compete with heavily-subsidised imported bread, tuna fish, produce and other foodstuffs. The regime’s industrial and social policies boosted the exporting coastal cities at the expense of the domestic-producing interior.

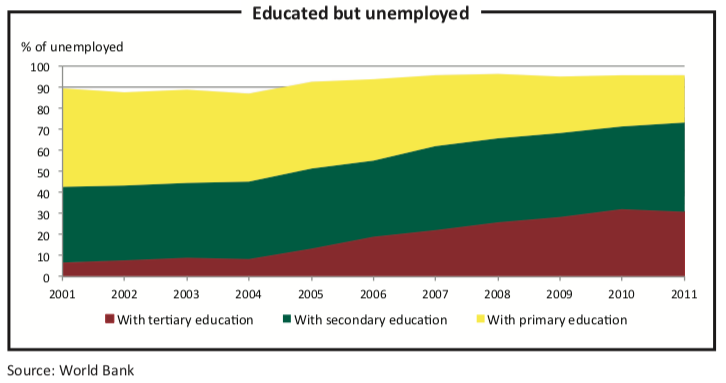

Despite its many shortcomings, the former government invested more equitably in higher education. Since the early 1990s schooling has skyrocketed, especially in the interior. The proportion of Tunisians without any formal education is over 50% among people over 60, but less than 18% for those under 40, according to a 2010 employment survey by the Tunisian Institute of Statistics (INS).

Tunisia is at the peak of its demographic window of opportunity. In 2012 its dependency ratio (under-14s and over-65s as a percentage of working-age 15-64s) was 43%, according to the World Bank. A majority of Tunisia’s roughly 10m people are under 35.

Tunisia’s young population, however, is struggling with high unemployment, which has been hovering above 30% for the last decade, according to the INS. Among certain tertiary-educated groups, especially in the interior, unemployment is a staggering 60%.

Tunisia needs a growth strategy that incorporates both halves of the country and leverages its economic assets, particularly its good infrastructure and well-educated population. It should link the interior’s natural resources and demographic opportunity with the coast’s export markets and create more skilled manufacturing jobs for its well- trained workforce. But what would such a strategy look like at the policy level?

In March 2011 the International Labour Organisation (ILO) published a report to promote inclusive growth in Tunisia. It called for creating more jobs for women, young college graduates and less-educated workers in Tunisia’s interior. The ILO study also recommended diversifying and expanding manufacturing, but did not shed much light on which industries to finance.

“The Atlas of Economic Complexity”, a book and online project of Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), does, however. It attempts to measure economic complexity across two variables: diversity, or the number of products a country makes; and ubiquity, the number of countries that make the same product. Strong economies have high diversity and low ubiquity, meaning that they can compete in the global economy with a wide range of products that not many other countries make.

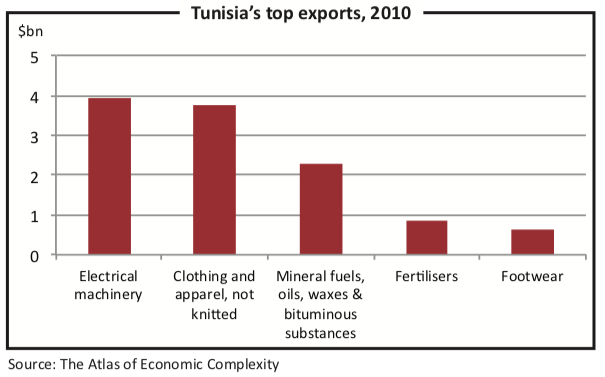

According to this measure, Tunisia’s economy is remarkably strong considering its small size. It is as diverse as Egypt’s despite having one-sixth the population. Tunisia exports manufactured goods such as consumer electronics (especially televisions), pharmaceuticals and car parts. This export basket also has the lowest ubiquity in the Maghreb, which gives Tunisia an advantage against its regional competitors.

Despite these regional advantages, Tunisia’s economic complexity is still below average when compared to countries with a similar GDP per capita. Tunisia’s GDP per capita of $9,795, adjusted for purchasing power parity, is just above China’s, according to the World Bank. But where China is ranked 29th in economic complexity, Tunisia is ranked 47th, according to the latest figures from the Harvard-MIT project.

Paradoxically, though, low complexity can indicate higher-than-average growth potential in the short term. This is because relatively unsophisticated economies can invest in new areas with reasonable expectations of quick gains. For example, a country that exports iron could produce steel with a high potential for a quick return while making its export basket more complex.

Bearing this in mind, the atlas’s authors look at Tunisia’s export landscape and pinpoint the industries that would most reward investment. They measure a new product’s value across two criteria: “distance” between the product and the economy’s capabilities; and “sophistication”, an indicator of that product’s potential benefit to growth. This potential benefit is measured by the average increase in GDP per capita seen in other countries that produce that product.

The garment sector is the area that would be easiest for Tunisia to enter, given its current capacity, according to the atlas. But making garments would yield fewer benefits than venturing into other sectors that might be more difficult. Products with higher potential value for job growth and export revenue include construction materials, petrochemicals, miscellaneous chemicals, home and office products, and machinery.

These are difficult sectors for Tunisia because they require skills the country currently does not have, given what it exports. Even so, policymakers and potential investors should recognise the lucrative opportunities these products represent to strengthen and diversify Tunisia’s economy.

To bolster capacity and competitiveness in these activities, economic policymakers in Tunisia should follow a three-pronged approach.

First, the government should unlock Tunisia’s foreign and domestic investment potential. The new government should continue its fight against official corruption by relaxing legal barriers to foreign investment that previously allowed regime officials to solicit bribes in exchange for a workaround.

Legislators should also strengthen Tunisia’s fractured banking sector and weak stock market. Tunisian banks are saddled with abnormally high levels of non- performing loans, 13% in 2010, among the highest in North Africa, according to World Bank data. The stock market is significantly undercapitalised at only $4.5 billion—one- tenth the value of the Moroccan exchange despite the countries’ comparable export baskets and GDP per capita, according to the World Bank.

The second pillar should be a coherent national policy that strengthens the links between education, innovation and the economy. Ties between universities and local industry are important for entrepreneurial innovation, which is often achieved when universities share research and exchange ideas with local industry as well as respond to regional industrial demands. Faculty could tailor curriculums to meet local business needs, develop on-campus entrepreneurial incubators for students and recent graduates, and provide on-campus job training.

The third pillar should be to reinvigorate the private sector to improve job quality and quantity. The government should empower small and medium enterprises by easing access to finance and lightening regulatory burdens in starting and pursuing business ideas. For example, entrepreneurs looking to create a business on an online or mobile platform are currently limited to the domestic market because Tunisians are restricted from holding foreign currencies.

Public-private partnerships could also encourage new business initiatives and foreign investment. Tunisia has succeeded in the past with similar ventures to extract phosphates and build infrastructure.

The new Tunisia, unshackled from a corrupt regime, has a potent new opportunity to use its educational and demographic strengths to explore inclusive, market-led industrial growth. But before this tale of two regions can be rewritten, there is work to be done. Improving access to capital and lowering the barriers to entrepreneurship are critical reforms that would make Tunisia more attractive to foreign investment, which is the cornerstone of industrial growth.