Nigeria: Boko Haram

Vigilantes and the army have chased the Islamist militant group from the city into remote hills

by Adam Higazi

In September 2013 a 19-year-old woman escaped from the clutches of Boko Haram. They had held her captive for three months in Borno state’s Gwoza Hills, an extension of the Mandara Mountains bordering north-east Nigeria and Cameroon’s far north. Boko Haram, in control of some villages there, abducted the woman because she is a Christian. They spared her life only after she went through a forced conversion to Islam.

Boko Haram claim to be fighting for a religious cause: to create an Islamic state and society free of secular, non-Muslim influences. The late Muhammad Yusuf founded the movement in 2003 in the city of Maiduguri, the Borno state capital, but it only began its armed struggle against the Nigerian state in 2009. Since then, their insurgency and the counter-insurgency of the Nigerian security forces have claimed many thousands of lives across northern Nigeria, with most fatalities in Borno and Yobe States.

Boko Haram is a nickname – probably first coined by Maiduguri residents, but popularised in the Nigerian and Western press. Their sobriquet was inspired by their opposition to secular influences on society, including Western education (karatun boko in Hausa), which they have declared is haram (forbidden by Islam). They have also banned working for the Nigerian government or civil service and they are violently opposed to Christianity and religious pluralism.

The Islamic religious establishment in northern Nigeria has roundly dismissed the Boko Haram doctrine as lacking an Islamic foundation. Much larger Islamic movements than Boko Haram are active in northern Nigeria, and, for the most part, strive to accommodate the pursuit of Islamic and Western knowledge, as well as secular and Islamic systems of government. The insurgency in north-east Nigeria has now become so violent and indiscriminate that many Muslims deny Boko Haram are really an Islamic movement. Perhaps they should not be called “Islamists”, but rather an armed group that draws selectively from Islam and has deviated from accepted religious practices and ideas.

Before founding the movement, Mr Yusuf led an Islamic youth group at the Indimi mosque in Maiduguri from 1998-2003. It was there that he started preaching against secular government and Western education. The Islamic authorities at the mosque, one of the largest in Maiduguri, opposed his preaching and ordered him to stop. He refused and broke away with some of his wealthy followers, establishing his own mosque, also in Maiduguri, in 2003. This became the group’s base and from there the Boko Haram movement spread to several states in northern Nigeria, gaining most traction in Borno and Yobe.

The Borno State government and security agencies were slow to react to Boko Haram, despite Muslim leaders alerting them to the threat. The sect was left to recruit and radicalise followers, mostly youth from across the social spectrum. In 2004 a faction broke away from Yusuf’s main group in Maiduguri and set up a base near the village of Kanamma, in northern Yobe State. They were known as the muhajirun(emigrants) and included some of Boko Haram’s original core, who had influenced Mr Yusuf’s preaching. It was reported that they split from Mr Yusuf because he had become “too liberal” with the ideology. Among them were several former University of Maiduguri students who had rejected their education and torn up their certificates. After they moved to Yobe they launched a string of attacks on police stations, fought the army, and were given the nickname “the Nigerian Taliban”.

Mr Yusuf’s insurrection began in July 2009, triggered by alleged government harassment and a police shooting that injured several Boko Haram members. The violence started in the city of Bauchi and spread across north-eastern Nigeria. Riding motorcycles, Boko Haram members launched co-ordinated attacks on police stations, raiding the armouries for guns and ammunition. The late President Umaru Yar’Adua called out the military troops, which cracked down on the sect. The main battleground was Maiduguri, where more than 1,000 followers of Boko Haram were killed in the ensuing violence, along with many innocent civilians. Soldiers captured Mr Yusuf, handed him over to the police, who after a short interrogation shot him dead.

Within a year Boko Haram had regrouped under a ruthless new leader, Abubakar Shekau, swearing to avenge the deaths of those killed in 2009. In the following years, Boko Haram acquired much more sophisticated weapons, purchased through the regional arms trade and by attacking military barracks. They began their comeback by attacking prisons where their members were detained. They also targeted policemen and carried out assassinations of Muslim clerics who opposed them, Christians and individuals who had collaborated with the security forces during the 2009 crackdown. In 2011 Boko Haram began a campaign of suicide bombing, the first in Nigeria’s history.

Boko Haram’s active supporters may range from a few thousand to 10,000, but there are no firm statistics. This estimate is based on the group’s recorded activities in different areas of northern Nigeria and their current absence in much of the region. The insurgency is now concentrated in Borno and Yobe with smaller pockets in other northern states. But they are mobile and may still have the ability to attack targets outside of the far north-east. To date there have been no Boko Haram attacks in southern Nigeria

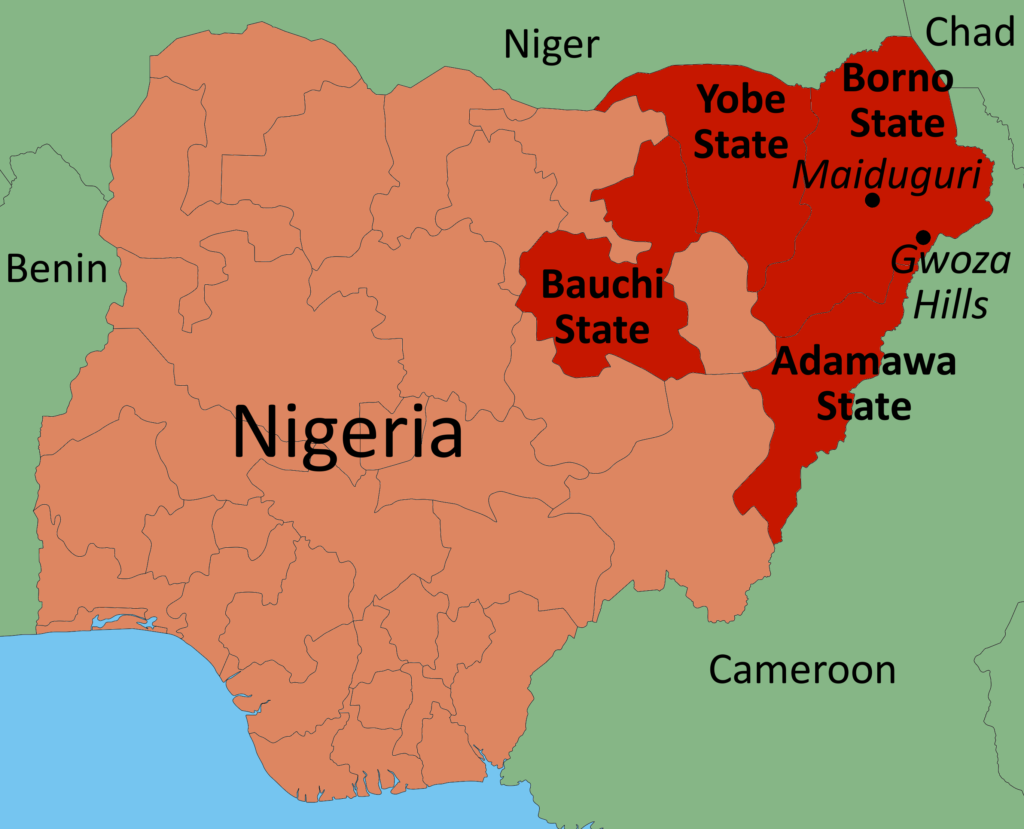

On May 14th 2013, the federal government declared a state of emergency in three north-eastern states: Borno, Yobe and Adamawa. It boosted troop numbers in these states. This subsequently led to the creation of a new Nigerian army unit, the 7thDivision, now based in Maiduguri.

Maiduguri, Boko Haram’s home base, has experienced an uneasy peace since July 2013, mostly because civilian vigilantes, with military help, have driven the group out. Maiduguri is a tight-knit city, and the civilian JTF (CJTF), as the vigilante movement is known, identifies the Boko Haram members, hands them over to the military, and in some cases kills them.

Attacks by Boko Haram have dropped off sharply in all areas of northern Nigeria except Borno and Yobe states, where in some areas violence has increased. The current absence of insurgent attacks outside of those two states is due to a combination of security measures taken by the federal and state governments and local resistance to the ideology of Boko Haram, which has not gained enough local support to sustain itself. In Borno, the movement’s stronghold, insurgents have largely moved out of the principal towns because of the vigilantes and the increased strength of the military forces.

For the most part the vigilantes carry sticks and machetes rather than guns. They have also sustained heavy losses in some areas of Borno after falling into Boko Haram ambushes. The group’s increased violence against Muslim civilians is largely a reaction to the CJTF, which is essentially a youth uprising against them.

Boko Haram now regards anyone from Maiduguri as a traitor. In an attack at a town called Benisheikh on September 17th 2013, they overran the military outpost and then blocked the main road between Maiduguri and Damaturu, Yobe state’s capital. In an all-night killing spree, they murdered at least 160 people, according to press reports citing local authorities.

Boko Haram is now fighting a guerrilla war. From their rural bases, they are now staging attacks in urban centres and roads leading to the cities. They have camps in the vast savannah forest covering much of the southern axis of Borno and Yobe. This area includes the Sambisa forest reserve, where previously, as an itinerant preacher and trader, Mr Yusuf once sold gum Arabic, a thickener and stabiliser used by confectionery and soft drink manufacturers. He allegedly built up a following among villagers there.

Boko Haram is also strong in parts of the Gwoza Hills. This is where they kidnapped the young woman. This area has a linguistically diverse population, which comprises a Muslim majority and a Christian minority, with many religiously mixed families. Since May 2013, Boko Haram has been attacking Christians and burning churches, killing some and chasing others out of their villages. This is a new phenomenon as recorded violence between Muslims and Christians in the Gwoza Hills was non-existent before Boko Haram’s arrival.

I carried out research in Gwoza in September 2012 and have maintained my connections there. I interviewed the young woman who was abducted a week after her escape. For safety reasons, she will remain anonymous. Boko Haram kidnapped the young woman at her grandmother’s home in the Gwoza Hills in June or early July. Some time earlier Boko Haram had forced the grandmother to leave the village. When the two women went back to retrieve some of the grandmother’s belongings from her house, two armed men confronted them, including a relative. After beating the old woman they allowed her to go free, but they kept the young woman. Her captors forced her to trek for many hours across the hillsuntil they reached a Dghweɗe village called Gharaza, where they took her to Ibrahim Tada Nglayike, Boko Haram’s leader in the Gwoza area.

Here Boko Haram minions beat their 19-year-old captive with electric wire and ordered her to convert to Islam. When she refused,Mr Nglayike brought out a knife and was about to kill her. Then, her father’s cousin, who had earlier helped to abduct her, intervened and saved her life. Mr Nglayike then gave her a seven-day ultimatum to convert or be killed. After a week she adopted Islam, but since escaping has returned to Christianity.

During her three-month captivity, the insurgents made her cook and do other tasks including forcing her to carry ammunition during an attack on a police station. Mr Nglayike has a reputation in Gwoza as a feared local Boko Haram leader. But inside the group, his wife is more feared than he is, according to the young woman. Mr Nglayike’s wife is said to be ruthless and to have personally slaughtered a civilian vigilante. Other women associated with Boko Haram do not fight, but they are relied upon for reconnaissance missions.

The captive went to Gwoza town with two such Boko Haram women. She had spent the previous week faking a stomach ailment. Boko Haram had plans to marry her off to one of its members and decided to send her for a medical check-up. While in town, she told her chaperones that she was leaving and that if they attempted to stop her she would alert the soldiers in the town. They left her and she returned to her family.

Boko Haram’s wave of terror is still claiming hundreds of lives a month in Borno and Yobe.A major attack on military and police infrastructure in Damaturu on October 24th-25th 2013, inflicted heavy losses on security forces and civilians, proving that Boko Haram are still a force to be reckoned with.

The emergence of the CJTF, organised grassroots opposition, to Boko Haram is significant. The improved governance style and performance of Governor Kashim Shettima in Borno compared to his predecessor, who misruled the state and sponsored political thugs to maintain his power, is also encouraging.

However, as Boko Haram continues its insurgency from its rural camps, considerable insecurity still troubles areas of Borno and Yobe. The rebels have destroyed hundreds of schools, as well as clinics and local government buildings, facilities already in short supply in these states. Consequently, thousands of school-age children are not studying in classrooms and medical emergencies and illnesses are only treated in the state capitals, if at all.

There is an urgent need both to restore the presence of the state throughout Borno and Yobe and to reform and rebuild the educational system. This requires both the provision of adequate security and concerted and inclusive investment. Without these reforms, terror may continue to reign in north-eastern Nigeria.