South Africa: beyond the doom and gloom

by Gavin Davis

In the early 1950s, South Africa’s minister of native affairs, Hendrik Verwoerd, said: “What is the use of teaching the Bantu [black] child mathematics when it cannot use it in practice?”

Such deep-seated prejudice drove the apartheid policy that denied black children the same standard of education as white pupils. Today the legacy of Bantu education continues to haunt policymakers tasked with providing a decent education to children whose parents were denied it in the past.

Despite spending a fifth of its national budget on education (and dispropor- tionately more on “previously-disadvantaged” schools), the hard reality is that South Africa is not producing enough matriculants who can read, write and calculate at the levels required to compete in the global economy. This is clear from South Africa’s underperformance in international benchmark tests such as the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study and the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study.

High rates of teacher and pupil absenteeism, strike action, administrative bungling, unqualified teachers, crumbling infrastructure and a shortage of textbooks are often cited to paint a picture of an education system in irreversible decline. But beyond the doom and gloom, there are places where a different story is emerging.

Khayelitsha, on the outskirts of Cape Town, is one of the largest and fastest- growing townships in South Africa. Established in the early 1980s, it is now home to around half a million people. Many migrated here from other provinces in search of jobs and a better life. Despite free basic services such as water, electricity and sanitation, unemployment, poverty, overcrowding and violent crime persist.

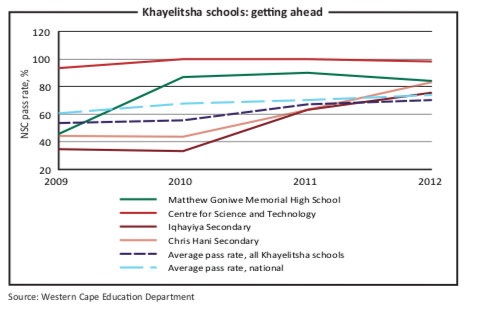

When it comes to education, however, the narrative is slowly changing. The Centre for Science and Technology (COSAT)—a specialist maths and science secondary school in Khayelitsha—became the first township school to be placed in the top ten schools in the Western Cape for the National Senior Certificate (NSC) examinations in 2011.

A rigorous selection process based on each child’s potential to do well in maths, science and information technology is partly responsible for COSAT’s success. Money plays a role too. Though parents pay a small fee, the state and, crucially, private sector donors pay most of the additional funding which ensures that the school has up-to-date equipment, learning materials and—most importantly—qualified teachers who care deeply about helping children to succeed.

The COSAT story has been well documented in South Africa and abroad. What far fewer people have noticed is the steady but undeniable improvement in the other 20 (non-specialist) secondary schools in Khayelitsha over the last few years.

In 2009 the average pass rate for the NSC examinations in Khayelitsha schools was 53.6%. By 2012 it had risen to 70.2%, not far off the national pass rate of 73.9%.

Even more encouraging is the concomitant decline in the number of “underperforming” (an NSC pass rate of 60% or less) Khayelitsha schools from 15 in 2009 to just four in 2012. Behind these numbers are individual schools that have shown phenomenal improvement in a very short time. Take Matthew Goniwe Memorial High School, for example. In 2009 this school was struggling with a matric pass rate of just 45.5%. Last year, 84.2% of the pupils who wrote the NSC passed—a full ten percentage points above the national pass rate. Iqhayiya Secondary and Chris Hani Secondary showed similar improvements. Iqhayiya’s pass rate was 75.6% last year, up from 34.6% in 2009. Chris Hani went from 44.2% in 2009 to 83.3% in 2012.

Some South African education experts argue that the pass rate is a crude measure of school performance, open to manipulation by schools that hold back weaker pupils from writing the NSC examinations, thus artificially inflating the rate. Other performance measures need to be taken into account, such as the total number of students who wrote and passed the NSC examinations, and how many did well enough to gain admission to university.

In 2012, 54 fewer Khayelitsha pupils wrote the NSC examinations than in 2009. But over the same period, exactly 500 more Khayelitsha pupils passed the NSC examinations: 2,038 in 2012 compared with 1,538 in 2009. Of those who passed, 584 qualified for university entrance, compared with just 305 in 2009.

What is behind the improvement in Khayelitsha schooling in the last three years? “It’s nothing sexy or dramatic,” said Clive Roos, special adviser to the Western Cape’s education minister. “The department simply got its house in order.”

In 2009 the incoming minister inherited an “ad hoc amalgam of peculiar things”, without a clear departmental plan, Mr Roos said. “The mere fact of having a plan changed everything completely.”

One of the first components of the new plan was a focus on appointing good principals in underperforming schools because, as Mr Roos put it, “If the principal is not right, the chances of turning a school around are significantly reduced.” So, for the first time, the Western Cape Education Department began exercising its prerogative to improve the choices of school governing bodies, with roughly a quarter of principal appointments queried on the basis of competence in the first year.

Another early intervention was setting a pass rate target for each school and publicising it. “Three years ago, when the minister visited a school, the principal often didn’t know their own school’s pass rate. Now it is the first thing that gets discussed,” Mr Roos said. Once the target is set, each principal is expected to draw up a tailored School Improvement Plan or SIP with the school governing body. The SIP is the department’s online management tool that monitors key performance indicators such as: the number of students on the nutrition and transport programmes; the average number of absent days per pupil and teacher; and the number of meetings held with parents to discuss their child’s academic performance.

Khayelitsha has also benefited from a strategy launched in 2010 to provide extra support to all the province’s underperforming schools, according to Bronagh Casey, spokeswoman for the Western Cape’s education ministry. The plan includes providing textbooks to all grade 12 students in their six core subjects, extra tutoring over weekends and school holidays and broadcasting extra lessons to schools via satellite.

Bantu education’s legacy will continue to be felt in South Africa for some time. The Khayelitsha story shows that a well thought out plan that emphasises accountability, departmental support and appointing the right people in the right places can improve performance in a short space of time.