“Sexploitation” in Ghana

by Afua Hirsch

Yvonne Ntiamoah, a resident in the Ghanaian capital Accra, was driving her two daughters home when she heard something on a local radio station that she could simply not endure.

“The presenters were having a discussion about a seven-year-old girl who had been raped or, as they called it ‘defiled’,” said Ms Ntiamoah, a lecturer at Radford University in Ghana. “It was just so graphic; they were describing how the man had lured the little girl into his room; how he was on top of her, and then they began imitating the sound effects, imagining what it would have been like.”

“The tone was light-hearted,” Ms Ntiamoah continued. “It was just horrible.”

The academic was so incensed that she drove to the studio of the radio station, which broadcasts in local Ghanaian language Twi, and made a formal complaint. “They said they would look into it,” Ms Ntiamoah said. “But I think it would take continuous protests and complaints to get any change.”

In Ghana and other West African countries, radio, television, newspapers and other media often treat rape, even child rape, as light-hearted, even salacious stories.

For instance, the Ghanaian press recently featured a story about Joshua Drah, a medical student who raped at least 52 female patients under the pretext of carrying out abortions. It included a passage that read:

“Interestingly, the doctor slept with all the women without using a condom and he bonked them standing, while they lay haplessly on the operation bench.”

The story was accompanied by a cartoon-like image of a stethoscope wrapped around the words “Doctor! Doctor!”, displayed in a humorous font, with one of the letters depicted as an open mouth with a tongue hanging out.

“The reporting of the [sic] Joshua Drah particularly stood out to me as an example of how blatant this problem is in Ghana,” said Nana Sekyiamah, a feminist writer and programme officer at the African Women’s Development Fund, an NGO. “Journalists are seeing these incidents as sex—something salacious and scandalous that is going to bring a lot of attention to their website or newspaper. They are not seeing this as rape—a crime and an act of violation.

“To me this stems from a hypocrisy within Ghanaian society where we have this conservative attitude towards sex, but we don’t even recognize when a sexual crime is being committed.”

Sexual assault and child rape are a serious problem in many West African countries. Poor policing practices, a lack of awareness among family members about how to deal with the trauma of sexual crimes, and poverty—which results in many children living and working on the streets of densely populated urban areas—have contributed to dramatic levels of under-reporting.

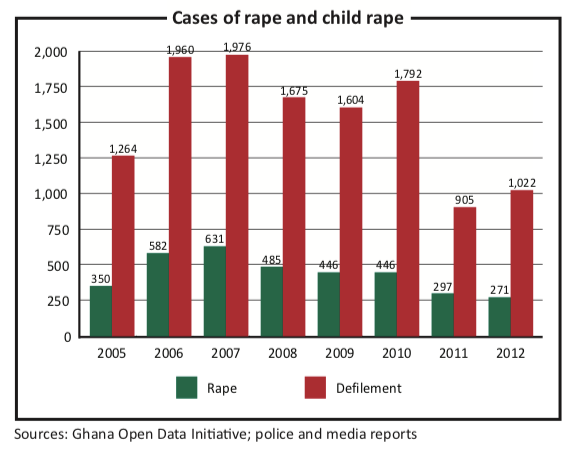

In Ghana more than 1,000 children are raped each year, three times as many as adults, according to the government. Whilst there has been a slight decrease in reported adult rape cases—with 271 cases reported in 2012 compared to 297 in 2011—there has been an increase in child rape cases, still referred to in the country as “defilement”, from 905 cases in 2011 to 1,022 in 2012, official figures show.

Child rights groups say that the real figure for both rape and child rape is as much as 90% higher and that the majority of cases are not reported.

“Sexual violence is a real problem here in Ghana. It’s very difficult to get specific data,” said Angela Dwamena-Aboagye, founder of the Ark Foundation, which works to protect women and children in Ghana.

“From the newspaper reports, from the cases we receive, and from the cases that reach the police, we know that that is an under-reported crime. And as a problem it is not being addressed properly, both in terms of prevention and prosecution,” Ms Dwamena-Aboagye added.

The press also do not know how to report on crimes of sexual violence. A senior print journalist, who did not want to be named, blamed the media’s difficulty with reporting rape and other crimes on two related issues: journalists’ training in Ghana and other West African countries; and the lack of awareness among editors.

“The reality is that journalists and editors are focused on selling papers, and sex sells,” said the journalist, who has called for more training on gender and reporting of criminal offences. “Newsrooms in Ghana are still very male-dominated and until there are a critical mass of women, or men who have been trained to approach these crimes with greater empathy, then this is a very difficult culture to change.

“Other countries like Liberia and Sierra Leone that have been through wars where rape was recognised as a problem have had to do a lot of work on this issue, but I feel there is a complacency in Ghana where we have not had such a brutal past but where this everyday ignorance still prevails,” the journalist added.

Ghanaian law has been relatively slow to adapt to modern views about rape and domestic violence. Marital rape in Ghana was criminalised only in 2007, under a new law that removed the presumption that married women had “perpetually” consented to sex while married.

Recent data on general levels of gender-based violence against women is scarce.

A 1998 report found that “violence is a reality for a substantial number of women” in Ghana, and that 72% of the respondents in a survey reported that wife beating was common. Of the male respondents in this study, 5% admitted to forcing their wives or girlfriends to have sex with them. “This happens when women request money from them and deny them sex in return,” the report found. “[Forced sex] is meant to settle the quarrel between them.”

The latest data from 2008 showed that 20% of women had experienced physical and/or sexual violence from their partners in the last 12 months, according to a report by UN Women.

Judicial and other staff in the courts and criminal justice system hold discriminatory attitudes towards women, gender rights advocates say. This discourages female and child victims of violence from coming forward.

“The kind of attitude that many people, including reporters, have is that these crimes are ‘just’ a rape, and that it just means somebody [is] sleeping with another person,” said the Ark Foundation’s Ms Dwamena-Aboagye. “They don’t understand the impact for many women and children that [this] is like a living death.”

One of the consequences of the flippancy with which sexual crimes are reported in Ghana and other countries in the region is the exposure of victims, experts say. News websites in countries including Ghana, Senegal and Nigeria frequently post pictures of the accused and, in some cases, video footage of the attack.

The Nigerian website talkofnaija.com posted the following headline last May: “Girl Now Pregnant Was Gang Raped at 11years [sic] By 20 Men [PICTURES]”. This is a typical headline on this site, which features similar stories from West Africa and around the world.

Senior figures in the criminal justice system are beginning to make high-profile calls for a change in the way reporters deal with sexual violence. Supreme Court of Appeal Justice Yaw Appau earlier this year cautioned journalists that their reporting of rape cases is exposing victims and compromising criminal proceedings.

The Ghanaian government has made some moves to increase awareness of sexual and gender-based violence. In 1998 it established the Domestic Violence and Victims Support Unit. In 2007, despite a lukewarm reception from many MPs, Ghana’s parliament finally passed the Domestic Violence law following intense lobbying by gender activists.

But little has been done to tackle the treatment of rape and sexual violence in the national media. And in a region where many countries are becoming economic success stories, donors are becoming less interested in funding programmes that seek to reform attitudes towards women and sexual violence.

“Civil society organisations who do this work are very few and far between,” Ms Dwamena-Aboagye said. “Donors are not interested in funding this kind of work any longer—they are interested in governance, oil and gas, consolidation of democracy, which is all fine, but they forget the social fallout, issues of the very poor, issues of children, of girls. So it makes it difficult to sustain work in this area.”