Namibia’s fisheries: heading for a rough patch

by John Grobler

The Namibian fishing industry, widely considered one of Africa’s best-managed, is heading for stormy waters. A combination of a depressed Spanish market, rising operating costs and a proliferation of new quota holders is leaving the sector awash in red ink.

Namibia is Africa’s biggest white fish producer overall, and the biggest exporter of white fish to European markets, according to Marcos Garcia Rey, a researcher at the University of Barcelona’s social studies department. The country’s fishing industry is recognised as a poster child for successful management of a dwindling asset on a continent not often noted for careful marshalling of resources.

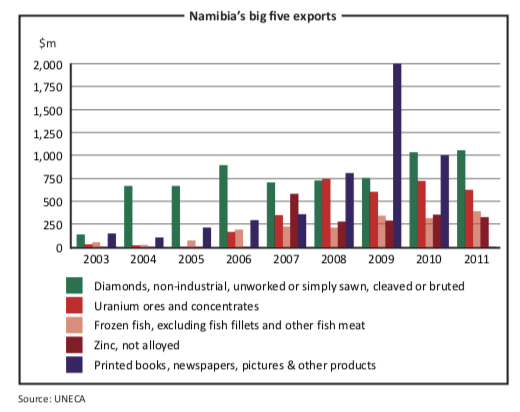

Fishing is the third-largest contributor to Namibia’s export earnings for 2011, according to the UN Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA). It employs some 24,000 people including 12,825 fishermen in 2009–2010, according to the Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources. The government is deeply concerned about the industry’s steady decline, mostly because it might cost it votes in elections scheduled for 2014.

Namibia benefits from the Benguela current’s rich waters, one of only four major oceanic upwelling systems, which teem with plankton. Its seemingly endless bounty has for centuries attracted whalers, guano and seal harvesters, and the world’s fishing fleets.

But by the early 1900s, the whales had disappeared and by the late 1960s, the main feedstock — the pilchard that every other large species feeds on — collapsed precipitously after heavy overfishing, especially by South African fleets.

When Namibia became independent in 1990, South Africa retained control initially of the former enclave of Walvis Bay and its attached fishing industry. In 1993, Namibia incorporated this harbour town, the country’s main port apart from Lüderitz. At the time, foreign hands controlled most of what was left of the industry and the pelagic resource, like everywhere else in the world, had all but collapsed.

The new government pursued a two-pronged approach to its fisheries: preserving and building up what was left of the resource, and increasing local ownership to reflect the aspirations of an independent Namibia after a decades-long campaign against apartheid South Africa. To preserve what little was left, the Namibian government in 1991 declared a 200 km exclusive economic zone and promptly arrested a brace of Spanish trawlers for fishing illegally in Namibian waters.

In many ways, it was too little, too late. From exporting 17,000 tonnes of lobster tail and 300,000 tonnes of pilchard (most of it as fishmeal fertiliser) in the late 1960s and early 1970s, mostly by South African-owned companies, Namibia today exports a few hundred tonnes of canned pilchard and hardly any lobster at all, according to economist Charles Courtney-Clarke, an expert on Namibia’s fishing industry.

From being the biggest employer in Lüderitz in the 1970s and 1980s, the Seaflower Lobster Corporation steadily collapsed to the point where it turned from a private lobster fishing and packing outfit into a state-owned hake fishing company in the mid 1990s, largely to save about 2,000 jobs. Lüderitz had a diamond rush in the 1900s that ran out 15 years later. It then boomed again in the 1970s on lobster. It risks becoming a ghost town again.

The supreme irony, however, is that the most valuable fisheries — mid- and deep-water hake — are by and large still in Spanish hands 20 years later. Shortly after independence, Spanish companies made joint venture agreements with local quota holders and took over the former South African-owned companies. Hake, a white fish, is Spain’s favourite fish. The exchange rate has made it more profitable to export hake to Spain (and to the rest of Europe via Spain). The global fishing industry, driven by its desire to make a quick buck on lucrative fishing quotas, has often worked against national interests, including the preservation of the resource itself.

When Walvis Bay was reincorporated, the Namibian government was faced with a quandary: it wanted to create more jobs but it was hobbled by a near-total lack of capital or equipment to take advantage of the resource. Under the late Dr Abraham Iyambo, who died suddenly earlier this year, the fisheries and marine resources ministry attempted to balance the many competing interests by pursuing a pragmatic approach and encouraging on-shore processing. But this required large investment in factories and processing equipment that only the Spanish could offer under generous, EU-subsidised incentives.

The success of “Namibianisation” was to some extent illusory. Faced with quota holders who simply sold their rights to the Spanish factories, the government ordered that such rights could be moved only by processing the hake on behalf of the Namibian rights-holders in local factories. But the Spanish companies owned the factories in Spain and Namibia. Nothing changed.

By 2010 the Namibian fishing industry was growing steadily, generating jobs and foreign income, and creating wealth for the local partners of the Spanish players. Independent fishing industry consultant David Russell estimates that 40% of all Namibian hake was exported to Spain in 2010–2011.

Under Bernard Esau, the new fisheries minister who took over from Iyambo in 2010, the government at last bowed to political pressure and more than doubled the number of quota holders to 145, while also increasing the hake quota from 140,000 to 170,000 tonnes, against the advice of its own scientists.

The result has been a study of unintended consequences. Factories that once were allocated a 20,000 tonne quota were reduced to 10,000 tonnes with the balance given to new quota holders who sometimes had no boats or factories. The profits at packing and processing plants started disappearing as quickly as the pilchards. To maintain their economies of scale, the companies made deals to catch the smaller quota holders’ allocations on their behalf and to share the profits. Months after the new quotas were announced, the first truly locally-owned fishing company, Etale, declared bankruptcy.

Moreover, as the economic recession started biting deeply in Spain, the demand for white fish has also plummeted, forcing notable players such as Pescanova (the biggest of the Spanish players in Namibia) into bankruptcy. Fuel costs, the single biggest expense in operating a fishing fleet, have steadily risen to where operational costs are now threatening to swamp the bilges.

Catches have declined, as many of the new entrants could not fulfil their quotas last year because of many factors including increased fuel costs, excessive prices demanded by smaller quota holders, adverse weather, declining stocks and new entrants who rely on the Spanish and do not look for new markets. As a result, a large number of quota holders (including previous quota holders who still owe levies dating back two years or more) have not paid their quota fees, Esau recently admitted in parliament, thereby hampering his ministry’s effectiveness.

Elsewhere, the news has also been bad: once robust tuna fishing has also declined to the extent that hardly any quota holder was still in business as the albacore tuna suddenly disappeared. The fishermen blame this on seismic surveys by companies searching for offshore oil and gas.

And, as if the Walvis Bay harbour’s waters were not choppy enough, there’s another perfect storm brewing: negotiations between Namibia and the European Union on the (EPA), which give Namibian fish tariff-free entry to the European market, have been very sticky.

Six years of negotiations have not brought the parties any closer, as Namibia fears being swamped by heavily-subsidised European agricultural products. A final deadline has now been set for 2016. Should no agreement be reached, Namibia could lose preferential access to its largest market for white fish in Spain — and those Spanish investors could be forced to up stakes in Namibia.

Perhaps more significantly, horse mackerel — a low-value species typically exported whole to other African countries — has recently overtaken hake as the industry’s most valuable export product. But very little processing is done on horse mackerel; it is an export product that creates few jobs. Moreover, the government now plans to levy a stiff tax on such exports.

The root cause, experts say, is that the fisheries ministry does not appear to coordinate its policies with the trade and industry ministry. Appeals for assistance never seem to reach the offices of either minister. As long as the right hand does not know what the left hand is doing, those manning the tiller will remain blind.