Madagascar: gearing up to vote

by Annelie Rozeboom

Madagascar is priming itself for the island’s most important elections in a decade. Since the political crisis in 2009 when Andry Rajoelina and the army removed the elected president, Marc Ravalomanana, the country has floundered without a democratically-elected government or parliament.

In September 2012 Rajoelina and the opposition parties signed an elections roadmap agreement after three years of protracted negotiations led by the Southern African Development Community (SADC). After overcoming much mistrust and disbelief from observers and voters alike, the country is now gearing up for the presidential poll set for 24 July.

Justine Sija, a seafood vendor from the south-western fishing village of St Augustin, is one of millions looking forward to the event. She has voted in all eight of Madagascar’s presidential elections held since 1965. “In the beginning we voted for President Tsiranana because we had to, but he was the best president in any case. In his time, things were cheap. Since then, presidents have changed, but prices just keep going up. I would like a president who could solve this problem and who will give us aid. But I’m not sure how reliable the tally is, as I know that even here in the village officials used to steal votes.”

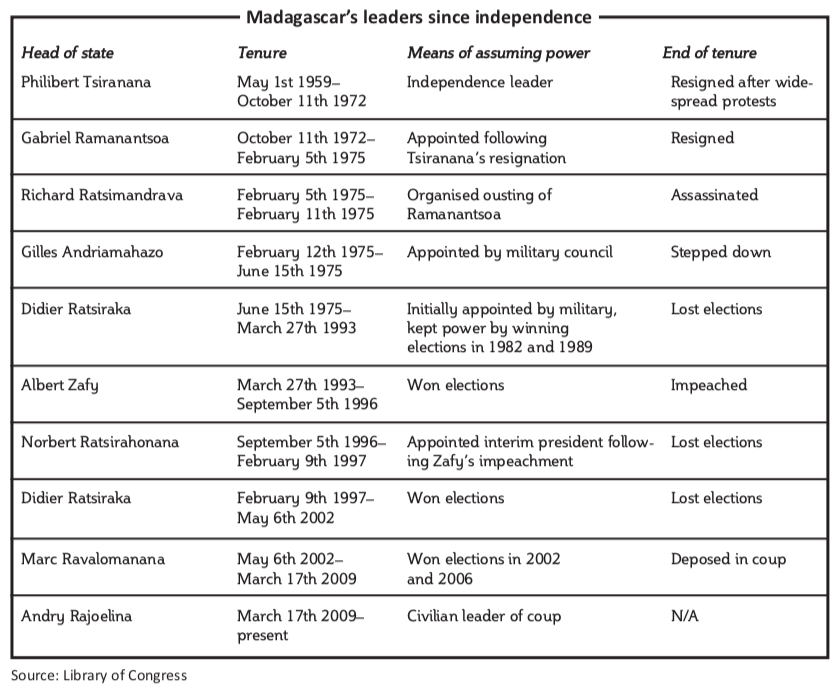

Election troubles have plagued this Indian Ocean nation ever since its independence from France in 1960. Philibert Tsiranana, who became Madagascar’s first president in 1959, was the only candidate in the island nation’s first two elections, in 1965 and 1972. Though he won 99.7% of the vote in 1972, a popular uprising forced him out of office later that year and he handed over power to an army chief. Didier Ratsiraka took power in a 1975 military reshuffle and then won re-election in 1982, 1989 and 1996. More candidates ran in these elections. Like Sija, few citizens trusted the results because the interior ministry ran the polls.

When Ravalomanana first ran for the presidency in 2002, the yoghurt tycoon dispatched his own helicopters to the polling stations to conduct his own tally. When his results differed from those of the ministry, a six-month long political crisis broke out, ending only after Ratsiraka, the incumbent president, sought exile in France. This ended his rule, which had lasted on and off for nearly 30 years.

The Independent National Electoral Commission of the Transition (CENIT), an independent election body helped by United Nations (UN) funds and advice, is in charge of the polls now. Its president, Beatrice Atallah, has served on earlier electoral commissions and she is currently a judge at the Appellate Court in Antananarivo, Madagascar’s capital. It is time citizens and not judges elect a president, which has been the practice after many previous disputed elections, she says.

Managing elections in Madagascar, the world’s fourth-largest island with a coastline of 4,827 km, is a staggering challenge. CENIT is equipping, manning and protecting 20,000 polling stations, up from 17,000 in past elections. The international community has donated $25m to the $60m electoral budget.

The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) has stepped in to help manage the funds and to advise CENIT. “Some places are so remote, you can only reach them by motorbike,” says Fatma Samoura, the UNDP’s resident representative in Madagascar. “We’ve asked South Africa to give us some helicopters for this. We know how to do this according to international norms and standards, from printing the ballots to deciding whose name appears first on the ballot. If they want the seal of the international community, they need to get it right.”

Voter registration is turning into the commission’s largest organisational headache. CENIT estimates that there are 10.2 million Malagasy over the age of 18 who are eligible to vote out of a population of 21 million. This is a rough estimate, however, as nearly one million Malagasy, mostly women in remote areas, do not have birth certificates, another rough estimate.

Birth certificates are needed to obtain a national identity card, which is needed to register to vote. Polety, 20, from Namakia, a small village in southern Madagascar, recently received her national identity card. Like many rural Malagasy, she does not have a family name. “The fokotany (neighbourhood council) chief comes once a year to register people in the village, but for some reason he never found me,” she says. Polety has now applied for a voter’s ID. “I want to be in this group of people who can vote. I will look closely at the face of the candidates, see what they’re like and listen on the radio to what they’re planning to do for us.”

Benjamin Ramaharosoa is president of the Soavimasoandro neighbourhood council in downtown Antananarivo. He works in a tiny office, two dark rooms with a few bare desks. Boxes filled with CENIT voter registration materials are stacked near the walls.

“During the elections in 2002, things weren’t done properly,” he says. “If you had a residency registration card from the fokotany they would let you vote.” But if you did not have a card or did not live in the neighbourhood, you could still vote: “The chief just needed to know who you were,” he adds. “Now we have proper preparations.”

So far, he has registered 11,200 people, but knows there are 700 who have not signed up. “We sent agents through the neighbourhood to talk to everybody. Some people still refuse to register. Sometimes they are convinced this election is organised by the HAT [the acronym for Rajoelina’s transitional government]. Others are illiterate and too scared to enter an office or even to hold a pen.”

A major feature of this election is a paper ballot, the first in Madagascar’s electoral history. Before, voters would enter a polling station, pick up a series of small photographs, place the picture of their preferred candidate in an envelope and drop it in the ballot box. This system encouraged fraud because interior ministry election officials could hide the photographs of opposition candidates. Sometimes, the smaller parties did not have the financial means to print photographs and place them in rural polling stations. This year, all candidates will be on the same ballot, which features a picture of every candidate, with his or her name and political party written underneath next to a box to be marked by the voter. For the first time, CENIT will print and distribute the ballots.

Samoura is encouraging political parties to monitor the election. “The politicians can send their people to the polling stations. Instead of complaining afterwards, they have the chance to make sure elections are fair from the beginning. A politician can deploy 40,000 supporters, put two in every station, and these people can complain as soon as the office closes,” she says. Party representatives can also fill out a written complaint during the voting process, which will be attached to the official voting operation log.

“We don’t have enough international observers to go everywhere and often you find problems in the small villages, where nobody wants to go,” Samoura added. “Instead of handing out T-shirts, politicians better make sure their people are there.”

These elections should be the cornerstone for establishing a stable democratic government, Samoura adds. “The real problem here is the mistrust between the civil society and its rulers,” she says. “People need to know that if they commit crimes, they will go to jail. Once there are solid institutions — a democratically-elected parliament, an independent judiciary and journalists who write articles based on facts — everybody involved in illegal trafficking, and they know who they are, will be judged. Their hour will come soon. But right now, the ball is in the court of the Malagasy. If they want democracy, they will have to go out and cast their votes. We can support them, but the rest is up to them.”

While the electoral commission has concentrated on the technical and operational aspects of the process, SADC has slogged through a list of political hurdles. First, the two rivals, Rajoelina and Ravalomanana, had to be persuaded not to run. Rajoelina finally agreed in January 2013, a move that has divided his Young Determined Malagasy (TGV) party. Four of his former allies are now running for president, opposing Antananarivo’s mayor, Edgard Razafindravahy, the official TGV candidate.

In a surprise move, however, Rajoelina changed his mind in early May and managed to get his candidacy approved. But he must step down 60 days before the elections and he must run as an independent as the TGV already has a candidate.

Rajoelina explained that he made his turnaround after Ravalomanana managed to circumvent his promise not to run by naming his wife, Lalao, as the candidate for his I love Madagascar (TIM) party. The electoral commission approved her candidacy and polls show that she may win.

The electoral commission approved a record-breaking 41 candidates for a place on the ballot, including Ratsiraka, the former president, now 76 and back from exile.

The elections roadmap also promises amnesty for all former political leaders.

Many fell out of political favour and were later convicted for committing economic crimes. “We have two more months for the courts to grant amnesties for all kinds of politicians, from presidential candidates to delegates,” Atallah says. “I understand how hard this is for the involved judges. These are people who were condemned. Now the judges have to undo those verdicts. It’s very hard on them.”

Atallah has already displayed her independence and determination to make the elections fair. In January Rajoelina tried to change the election schedule, asking for parliamentary elections to take place before the presidential elections, which he hoped would strengthen his political chances if his party won a majority in the legislature.

CENIT did not budge and the elections will go ahead as planned. Parliamentary elections will be held on 25 September, after the July presidential poll, and will be followed by local elections on 23 October.

Even if the elections are not perfect, they will be important for Madagascar, Atallah says. “If we can limit the problems and have elections that are as democratic as possible, we will at least be able to come out of this crisis.”