West Africa: science paves the way

by Christopher Pala

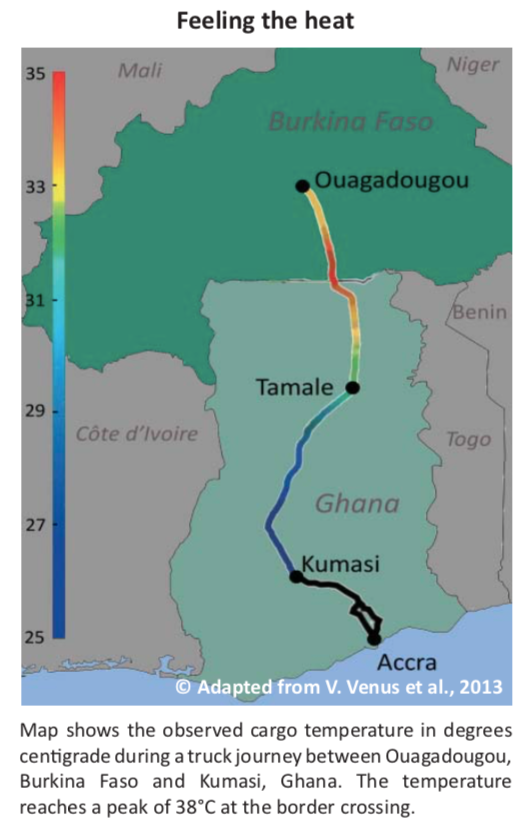

Each day scores of lorries laden with tomatoes, onions and other fresh vegetables start the 1,000 km trip from landlocked Burkina Faso to Accra, Ghana’s capital on the Atlantic coast. This journey — along smooth and tarred roads in the north and bumpy and unpaved roads in the south — should take between seven and 12 hours. The typical open 18-tonne truck crosses only one border, but stops up to 20 times as officials check documents and collect bribes. On the last 40 km stretch, the lorry sways precariously from side to side as it avoids crater-sized potholes. By the time it gets to port, often two days later, most of its produce is perished.

Every year an estimated 1.3 billion tonnes of food, about one-third of the food produced for human consumption worldwide, is lost or wasted, according to a 2011 Food and Agriculture Organisation report. In industrialised countries, significant waste takes place at the consumption stage: food is discarded even if fit to be eaten. In poor countries, predominantly in Africa, an estimated 40% of food is lost at post-harvest and processing stages. Poor infrastructure, corruption, transport, storage, processing and packaging are largely to blame.

This crucial issue of food spoilage was a topic of discussion four years ago between Valentijn Venus, a Dutch agro-meteorologist, and his colleagues at the University of Twente, in Enschede, the Netherlands. Venus noted that too much research focused on hunger, which is the result mostly of lack of starch, and not enough on malnutrition, which stems from a diet lacking fruits and vegetables. One scientist noted that a major African problem was the high quantity of vegetables that spoiled on the road between farms and markets.

This triggered an idea in Venus’s mind and he started researching how remote-sensing satellites could alleviate the problem. In autumn of 2009 Daniel Asare- Kyei, 35, left his native Ghana and arrived at Twente to complete a master’s in geo-information science. He was intrigued by Venus’s idea. He had first-hand knowledge that many of the tomatoes that come from Burkina Faso — considered tastier than the Ghanaian ones — are crushed or rot during the two-day trip. For his thesis, he suggested a project looking at post-harvest losses linked to the transport of tomatoes between these two countries.

After four years of research, the scientist and the graduate student wrote a computer programme that creates the best daily itinerary for tomato trucks plying this north-south corridor, significantly reducing the spoilage of the red, fleshy fruit. Their model was published in March 2013 in the journal Computers and Electronics in Agriculture.

Tomatoes, originally from Mexico, are one of the main vegetable crops in the developing world, according to Peter Hanson, a tomato breeder at the World Vegetable Centre in Taiwan. In Africa, where malnutrition is common, the fruit, which is used as a vegetable, is one of the main sources of Vitamin A and C, in which millions of people are deficient, he said. In the developed world, tomatoes are picked unripe and transported in air-conditioned trucks. But lorries travelling this West African route are often open flatbed vehicles, sometimes covered with tarpaulins.

Venus and Asare-Kyei began by studying data generated by weather satellites hovering over Africa. The satellites precisely map the sun’s intensity and the temperature of tar and dirt roads throughout the day. They thought that comparing the influence of these external conditions with the microclimate inside the lorry might reveal how tomatoes decompose.

So in 2009, Asare-Kyei made the first of three trips to Burkina Faso, traveling to Accra with trucks stacked with tomatoes. In each wooden crate he placed a sensor that recorded temperature, humidity, light intensity and bumpiness. Every time the driver stopped, almost every 15 minutes — sometimes to refuel, other times to pay a bribe — Asare-Kyei climbed into the truck and poked a few tomatoes with a penetrometer, a hand-held device that records the pressure it takes to break the fruit’s skin, providing a precise measurement of firmness and health.

With this information, the graduate student was soon able to match the proportion of broken or bruised tomatoes with the road and trip conditions. He found that at the end of a typical two-day journey, a startling 40% of the tomatoes were too rotten to sell. But this proportion varied widely, from 15% to 100%, depending on the trip’s circumstances and the driver’s itinerary.

Another team made several similar trips in 2010, collecting more information. Then the researchers created a climate chamber in Accra, which mimicked the temperature and humidity conditions inside a truck, and filled it with tomatoes. This allowed them to monitor how the fruit reacted to these conditions with a precision impossible on a moving vehicle, Venus explained.

Tomatoes, the data showed, decompose fastest when they travel on bumpy roads over long periods in environments that are hot, dry, sun-drenched or stuffy. Under these conditions, the spoilage rate varies between 50% and 100%. But when they move over smooth roads through tall forests that provide shade and coolness, as well as humid air with plenty of circulation, only 25% spoil. And if the trip takes one day instead of two, the losses drop to 15%.

Wholesalers based in Ghana and nicknamed “market queens” control the vegetable business in West Africa. They travel to the small farms in Burkina Faso, which cover an average of one or two acres. In the dry season, tomatoes are the main cash crop. The traders negotiate the quantity and price of the tomatoes. They hire the drivers and trucks to deliver the fruit to specific markets, where it is sold to retailers.

“I was able to speak to 10 of these market queens and some farmers,” Asare-Kyei said. “I was surprised they had very little idea of how much variability in the spoilage there is, let alone how to reduce it. And they didn’t fully understand that the biggest single cause of spoilage was the length of the trip.”

The “market queens”, aware that much of the crop may arrive decayed and unsellable, offer the farmers low prices, Asare-Kyei explained. Since the wholesalers come at irregular intervals, the farmer does not have the luxury of setting aside the not-quite-ripe, harder and more shock-resistant.

If spoilage is less than anticipated when the trucks arrive, the wholesalers keep the windfall profits. But if improved itineraries that reduce spoilage were available, Asare-Kyei and Venus surmised, competition would force the traders to pay the farmers more and sell the tomatoes for less. In addition, tomato consumption would rise and public health might improve, too.

So Venus and Asare-Kyei designed a computer programme that combines satellite weather data and road conditions along different routes. Mixed into this are traffic information, ideal departure times and the number of (often illegal) stops. It is a recipe that prioritises speed, coolness and shade as well as smooth and level roads while also avoiding traffic jams, long border queues and checkpoints.

We have created “a computer programme that can be used by governments, businesses and NGOs to make daily recommendations for the people who decide where the tomatoes go — in this case, the market queens,” Venus said. African radios already transmit traffic reports, he added. “They could just add the best itinerary of the day at the end of the news.”

It could sound something like this, Asare-Kyei chimed in: “For tomato sellers travelling between Ouagadougou and Accra, leave at five am. At Tamale, take the eastern corridor road through northern Volta, down to Hohoe in mid-Volta and continue south to Accra.”