Ghana’s gold star democracy is still shining.

by Afua Hirsch

There is a saying among political scientists that the more entertaining a country’s political process is, the less real policy is involved. This is a charge often levied at Ghana, which has now managed three peaceful transitions of power since 1992.

The run-up to Ghana’s December 7th 2012 elections gives a good sense of the state of Ghanaian society. Ghana has carved a niche for itself as a haven of order in West Africa, a region still plagued by political instability. This has not been lost on foreign investors, who channelled $7 billion into the country last year. Despite oil production falling short of expectations, Ghana’s continuing export and exploitation of new oil prospects means that the winner in December’s polls will have the means to hold onto power for a generation.

The spoils of power in newly oil-rich Ghana have done little to enrich its political culture, according to insiders. “Ideology is irrelevant in Ghana,” said the organiser of one major opposition party campaign, asking to be kept anonymous. “I think it comes from the universities—they teach people that the objective of politics is to win power, that it is a game you play by making your opponent sound stupid, rather than by engaging in rational debate. People make individual election promises, without any context, in a bid to win power, which rarely amount to policy and have no ideology behind them.”

The ruling National Democratic Congress (NDC), represented in the upcoming elections by incumbent John Dramani Mahama, is traditionally regarded as a centre-left social democratic party, associated with the working class. The National Patriotic Party (NPP), led by Nana Akufo-Addo, has a reputation as a centre-right liberal conservative party linked to the elite. However these labels have very limited value in Ghana: both parties advocate development and there is little to distinguish their ideological stance on individual policies. The NPP—supposedly on the right—is the party advocating free senior high school education

The NPP’s promise to introduce free senior high school education caught the public’s imagination and has become central to the campaigns of all eight presidential candidates. Half of them attract enough recognition to have a chance of winning significant votes, but the ruling NDC and opposition NPP are regarded as the real contenders for power.

“Education has certainly become a point of reference for politicians in this election,” said Bright Simons of Ghanaian policy think-tank Imani. “We have seen policy discussion in elections before—for example, during the 2000 election inflation in Ghana was running at 40% and this was a very significant election issue—but this is the first time that one policy [free high school] has been shared by all political parties as the main issue.”

The cost of secondary school education in Ghana has become prohibitive and the NPP’s promise to make it free sparked widespread debate. Many argue that until teacher training is improved and new schools are built, free education will benefit only a few.

Ghana’s education system was one of many issues that dominated a debate among four presidential candidates last October. The four-hour debate, held in the northern capital Tamale, also covered job creation, agriculture and taxation.

Some analysts say the new level of political accessibility created by the rapidly growing role of social networking sites has propelled policy into a more prominent position.

“People are showing an interest in policy in this election that I haven’t seen before, and I think it’s because of the way social media is adding to the conversation,” said Mac-Jordan Degadjor, a Ghanaian blogger and social media consultant. “Now messages are being spread by mobile phone—which almost everyone in Ghana has— making it easier for people to share their ideas.

“There is so much interest in the parties’ policies that when there was a power cut during the presidential debate, people went and found the nearest TV being powered by generators and car batteries so that they could still follow it and hear exactly what the presidential candidates were saying,” Mr Degadjor added. “Many of them are saying this year they are voting on issues—elections here are changing.”

While policy is becoming more relevant to Ghanaian voters, experts say personality still plays a huge role. Some predict increased support for the ruling NDC, stirred by sympathy for the late president and NDC flag bearer John Atta Mills, who died unexpectedly in July.

Former president Jerry John Rawlings still looms large over party politics. Mr Rawlings—who first seized power in a 1979 military coup and presided over Ghana’s democratic transition in 1992—stepped down from leading the NDC in 2001, after serving two terms as a democratically-elected president. In 1998 the NDC elevated the former flight lieutenant to the formidable position of “party founder”, a decision that seemed to entrench the cult of personality around him.

It was the decision of Mr Rawlings’s wife, former first lady Nana Konadu Rawlings, to found her own political party earlier this year, that has stirred the campaign’s greatest controversy. Mrs Rawlings’s National Democratic Party (NDP) positioned itself as a breakaway from the ruling NDC amidst reports that she was disgruntled at the NDC’s refusal to nominate her as its next presidential candidate. The NDP attempted to use the NDC’s popular umbrella logo, arguing that it belonged to Mrs Rawlings. This prompted vitriolic commentary among political enthusiasts in Ghana. Some see the former first lady as a Lady Macbeth-type figure, responsible for her husband’s political demise and splitting allegiances in the party he founded.

The election commission declared that Mrs Rawlings had missed the registration deadline and has prevented her from contesting the upcoming elections.

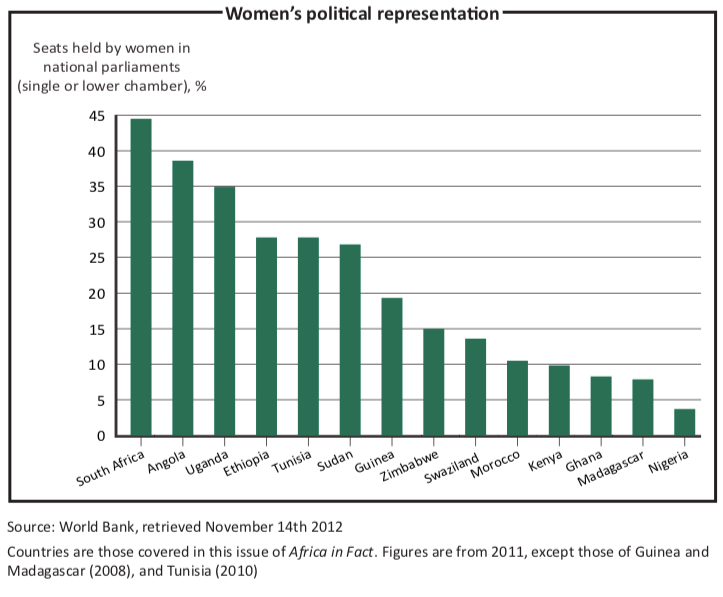

The prevailing attitudes against Mrs Rawlings may be evidence of a deep- seated prejudice that remains in the Ghanaian political system. None of the presidential candidates is female, although three parties have female vice-presidential contenders, leaving the high profile debates an all-male affair.

With a parliament that is only 8.3% women, Ghana is one of the worst- performing African countries in terms of female representation in politics. The December elections, however, will see a 30% increase in female participation, with 133 women competing with 1,332 men.

“I think what’s really bad is that none of the two major parties has chosen a woman presidential candidate or implemented affirmative action policies within their parties that will ensure that there is gender parity,” said Nana Sekyiamah, a feminist who works with the Ghana-based African Women’s Development Fund. “Personally I’m looking to the two main parties to provide this kind of leadership because the reality in Ghana’s politics is that power is likely to rotate between these two parties for a while. A woman presidential candidate from a party that is unlikely to win even a significant portion of votes is not going to shift the debate where women’s political participation is concerned.”

The male-dominated personality politics evident in Ghanaian politics are still regarded as second to the other issue that prevents policy from being truly prominent in this country’s elections: ethnic allegiances.

“Voting patterns are still based on ethnic loyalties,” Mr Simons said. “But it’s not always clear whether people are voting with historical factors that just happen to align with ethnic lines. But the main driving force of Ghanaian politics is still the raw pursuit of power,” Mr Simons added. “People want to win, and they want to win at all costs.”