Fewer than 16% of Ethiopians are connected to the national electricity grid. Many cook on firewood, charcoal and dung and die of indoor pollution. As this East African economy grows by leaps and bounds, the demand for energy is on the rise, too. The Ethiopian government plans to meet this need by harnessing the Omo River and building a hydropower dam. Lord Aikins Adusei finds the drawbacks in the project.

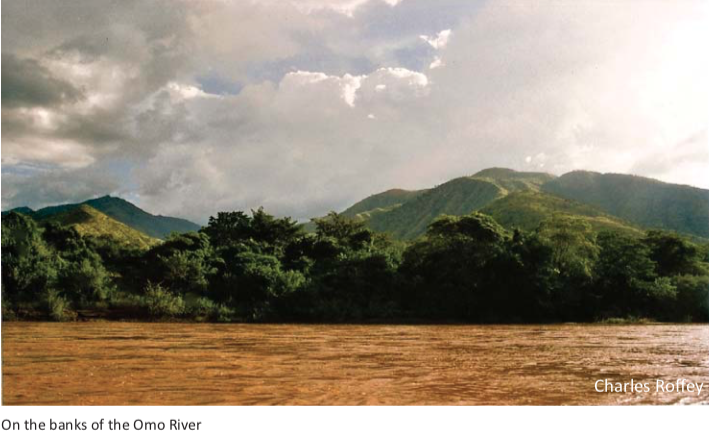

The Omo River Valley in south-western Ethiopia is home to more than a dozen tribes that have lived there for centuries and depend on its annual floods for their livelihood. Its waters flow south into Kenya’s Lake Turkana, considered the cradle of humankind because of the wealth of hominid fossils that have been discovered there. But now the river is the dividing line between a government that is driving development and environmental and human rights activists who want to protect the valley and its peoples.

At the centre of the conflict is the Gibe III hydropower dam, 470km southwest of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia’s capital.

The government wants to use the river’s waters to increase the region’s agricultural productivity and to fill its coffers by leasing the newly irrigated land to the highest bidder. It also wants to sell some of the dam’s excess electricity to neighbouring countries.

In addition to human rights and environmental concerns, opponents complain that the government awarded the construction contract without transparency. Fatal clashes in the area have already taken place as people have been displaced and compete with others for land.

In 2000, the state-run Ethiopian Electric Power Corporation (EEPCo) prepared a 25-year master plan to boost energy generation capacity to about 37,000 megawatts (MW) by 2037. Ethiopia’s current energy generation capacity is at around 1,080MW, according to the United States (US) Energy Information Administration (EIA).

The plan started almost immediately with the Gibe I and II power projects. Gibe I, completed in 2004, is a dam and Gibe II, still under construction, is a power plant associated with Gibe I. About 155km downstream from these two projects is the Gibe III hydropower dam, under construction since 2006. Upon completion, EEPCo says it will be Africa’s tallest dam at 243 metres.

Gibe III, expected to cost about $2 billion, is a public–private partnership between EEPCo and an Italian civil engineering company, Salini Costruttori.

EEPCo is providing $572 million with others funding the remainder, according to International Rivers, a US-based environmental group.

Investors have questioned the contract with Salini. The government awarded Salini the contract to Gibe I and II after an open tendering and competitive bidding process but it awarded the Gibe III contract through direct negotiations with Salini behind closed doors.

International Rivers states that this led the European Investment Bank to refuse to finance the project citing lack of transparency and poor procurement practices. The African Development Bank (AfDB) also pulled out after it found that the hydrological cycle in the area will change, shrinking the Omo River’s flow to Lake Turkana by 85%.

This left only the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, which has— according to International Rivers—pledged $500m and is now the project’s key financial backer.

On July 12th 2012, however, the World Bank agreed to provide $684 million to finance the transmission line from the Gibe III dam to Kenya, a move that has opposition groups rallying against the institution. The Bank is distancing itself from Gibe III by stating that the electricity transported on the line will come from “a large number of existing and future power plants in Ethiopia”, and not from Gibe III alone.

The hydroelectric project should be up and running by July 2013 and is projected to add 1,870MW of grid electricity to the current 1,080MW.

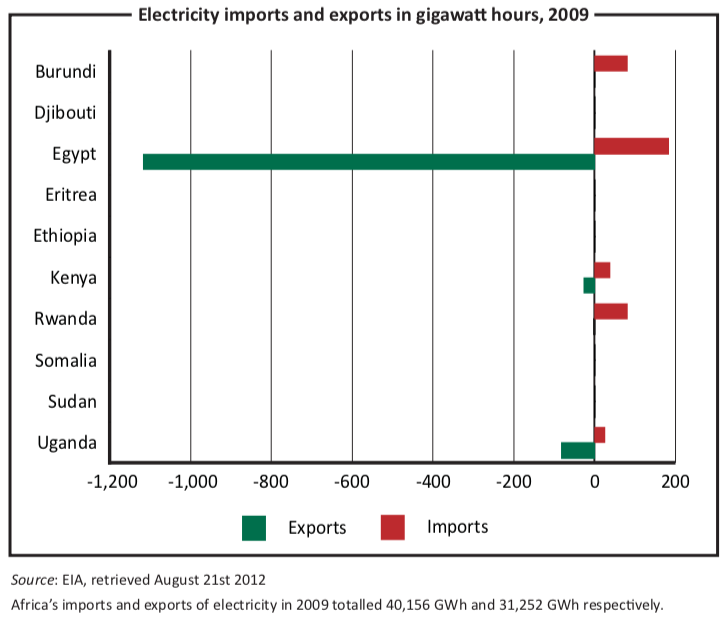

The expected energy generation will exceed Ethiopia’s needs but the government has a solution. It plans to export the excess to neighbouring countries: 500MW to Kenya, 50MW to Yemen and 200MW to Djibouti and Sudan. Ethiopia already sells 35MW of power to Djibouti for $1.5m a month, according to the Sudan Tribune.

With 84.7m people, according to the World Bank’s 2011 estimates, Ethiopia is Africa’s second most populous nation and the world’s 14th. It is also Africa’s fastest- growing non-oil economy, with an annual average growth rate of just under 10% between 2006 and 2011. Despite this growth, Ethiopia is extremely poor with a GDP per capita of $374, according to the World Bank’s 2011 estimates.

It is also extremely energy poor and one of the countries in the world with the lowest energy consumption. Less than 16% of the entire population has access to grid electricity with a wide gap between rural (about 2%) and urban populations (86%), according to Anton Eberhard and colleagues at the University of Cape Town.

But demand for electricity is rising by more than 17% annually, spurred by population pressure, urbanisation and high economic growth, according to Getachew Bekele and Getnet Tadesse, at the Addis Ababa Institute of Technology.

Blackouts often cripple the country, causing huge financial damage to the economy. The severe drought in 2003 led to power rationing which lasted six months and cost the Ethiopian economy more than $200m daily, according to CEE Bankwatch Network, the Central and Eastern European network for monitoring the activities of international financial institutions.

As a result, more than 95% of Ethiopians rely on charcoal, firewood and dung as primary sources of energy for cooking and heating, according to the World Health Organisation. Indoor pollution is a leading cause of death among Ethiopians, with more than 72,400 people dying from it in 2009.

Besides saving people’s lives, the Gibe III dam will create a lake that will irrigate large-scale sugar and biofuel plantations, the government claims.

But will these giant farms provide jobs for locals? Will the food produced feed Ethiopians or will it be exported abroad? How will it affect the tribal communities who rely on the river for their pastoralist activities? How many people will be relocated to make way for the dam?

More than 15 indigenous tribes live along the banks of the Omo River and near Lake Turkana, says International Rivers. The project will affect more than 1.5m people through displacement or food insecurity, according to various human rights groups. Many have registered their opposition to the project in a declaration to the African Development Bank: “We oppose any current push towards development that is driven predominantly by commercial interest and which undermines our indigenous economies and denies us the little control we have over our already undermined survival.”

Others are concerned about the loss of property rights and the conflict over resources that may result as people are relocated. “There is no shortcut to development,” said Ben Rawlence, senior Africa researcher at Human Rights Watch, a US-based non- governmental organisation. “The people who have long relied on that land for their livelihood need to have their property rights respected.”

Three years after construction began, the BBC reported on February 5th 2009 that fighting broke out between the Gheri and Borana people living in the project area. An estimated 300 people died and 100,000 were displaced. More recently, on July 28th 2012, the BBC again reported that 18 people had died after similar clashes over land ownership in the area. Approximately 20,000 people crossed to Kenya to escape the fighting.

Additionally, International Rivers contends that Ethiopian laws were broken when construction began without an environmental impact assessment or an environmental permit.

The UN’s World Heritage Committee has also expressed its “utmost concern”. Archaeologists have discovered many hominid fossils in the Omo River Valley, which was designated a world heritage site because of its contribution to the study of human evolution. The UN committee has pressed the Ethiopian government to cease construction.

Opposition groups have joined forces to stop Gibe III, but construction is going ahead.

Azeb Aznake, EEPCo’s Gibe III project manager, took a more conciliatory line but one that does not break the impasse between the two groups. “Water is our major resource,” she told French wire agency Agence France Presse. “We have to make use of it and develop; we have to eat three times a day like any human being, so there has to be compromise.”