Democratic Republic of Congo: migration and nationality

Citizenship questions are at the heart of the DRC’s conflict

Conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), particularly in the eastern Kivu provinces, can be traced to its convoluted history of migration, citizenship and property rights.

Four countries share borders with the Kivu provinces: Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi and Tanzania. The conflict in North and South Kivu is often described simplistically as a struggle between rebels (often supported by neighbouring countries), the national military and armed local “self-defence” forces. According to this narrative, the conflict began in the aftermath of the Rwandan genocide in 1994, and the three groups are now vying for control of the area’s natural resources: gold, tin, tungsten and coltan (used in mobile phone chips).

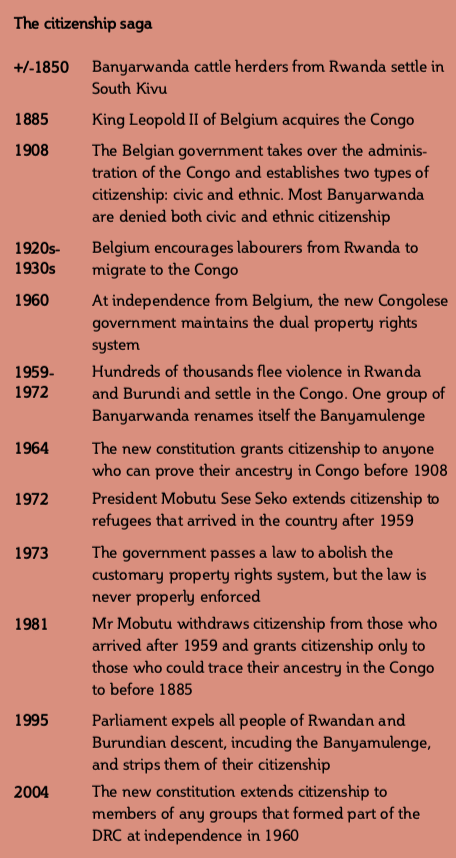

The origins of this conflict, however, are much deeper, and date back much further. Trouble in the Kivus began in the 19th century when Banyarwanda cattle herders from present-day Rwanda moved to the South Kivu hills. An exact date for this movement is not known, but historians estimate that they may have arrived around 1850. The conflict’s roots became even more entangled when the Belgian government took over administration of Congo in 1908 from King Leopold II, who had run the territory as his personal fiefdom since 1885.

Shortly after this takeover, Belgium established two types of citizenship: civic and ethnic. It granted civic nationality to the Belgian settlers and to a few Congolese the Belgians considered “evolved”. The great majority, however, were given ethnic citizenship, as Mahmood Mamdani, a professor of government at Columbia University, outlines in his book “When Victims Become Killers”.

Belgium also created a “modern” property system which guaranteed that its settlers could purchase land from the colonial government. In addition the Belgians created a system of “Native Authorities”, new administrations that granted formal control of “indigenous” land to each ethnic group that could trace its ancestry to 1885, when the Berlin Conference awarded Congo to King Leopold II.

For reasons that remain murky, the Belgians did not grant most of the Banyar- wanda groups indigenous status or native authorities, thus barring their access to land. This may be because their numbers were small. The Banyarwanda are barely mentioned in the ethnocartography of the Belgian Congo, according to the Chris Hug- gins, author of a 2010 report for International Alert, a London-based charity. This lack of recognition was the beginning of a narrative of “indigeneity”, which continues to have negative repercussions for the entire region’s politics.

Belgium also implemented migration policies designed to encourage—and at times force—labourers from Rwanda to move to the Belgian Congo in the 1920s and 1930s. This response to the labour shortage, created by King Leopold II’s brutality, set the stage for further friction and confusion about the Banyarwanda’s nationality.

For example, while the Belgians denied indigenous status to one wave of Banyarwanda labour migrants, according to Mr Mamdani, they extended this coveted status to another wave of Banyarwanda in 1936, who were considered permanent residents of the Gishari district in North Kivu, only to withdraw it again in 1957.

After independence in 1960, the 1964 constitution abolished the colonial citizenship structure. It granted nationality to those who could prove their ancestry in Congo predated 1908 (when the Belgian government took the reins from Leopold II), thus denying citizenship to the labour migrants who had arrived in Congo during the 1920s to 1930s and stayed.

The new government, however, retained the dichotomous colonial property rights system. The Banyarwanda thus became political citizens of the newly independent state but were still denied the right to control communal land. They remained compelled to live under the jurisdiction of other groups. If they lived on or passed through other people’s land, they were required to pay tribute.

During the 13 years between the 1959 Hutu revolution in Rwanda and the 1972 Burundian civil war, hundreds of thousands fled those countries into the Congo. At this time, some Banyarwanda in South Kivu, whose ancestry in Congo preceded 1885, became determined to differentiate themselves from these newcomers and to reassert their identity as Congolese. They began to refer to themselves as Banyamulenge after a mountain called Mulenge in South Kivu, near the village that they claimed their ancestors had founded in the 19th century.

Mobutu Sese Seko, who had seized power in 1965, also encouraged the emigration of pastoralists from Rwanda.

In 1972, according to Mr Mamdani, politicians from the Congolese Kinyarwanda-speaking community successfully lobbied the central government to adopt adecree that gave citizenship to those who had arrived as refugees, mostly Tutsi, during the 1959 Rwandan Hutu revolution. But for reasons that remain unclear, Mr Mobutu changed his mind in 1981 and revoked the 1972 citizenship decree. He replaced it with the former colonial standard of granting citizenship only to those who could trace their ancestry within Congo back to 1885.

In 1973 the government passed a law that sought to abolish the customary property rights system and established state control of all land. Meant to simplify land rights in the DRC, the law was never properly implemented. In the late 1980s only 3% of land had been registered under the new statutory system, according to the International Alert report. The dual property system per sisted, and the Banyamulenge and other groups were still excluded from controlling communal land.

In the 1990s the borders with the countries neighbouring the Kivus remained porous. Some Banyamulenge, suffering from discrimination and worried about their land rights in the DRC, crossed the border into Uganda to join the Rwandan Patriotic Front, made up mostly of Tutsi exiles from the 1959 revolution.

After the Rwandan genocide in 1994, nearly 2m mostly Hutu refugees fled into Zaire, as the DRC was known then, and neighbouring countries. During this time Mr Mobutu’s grip on power was slipping, as domestic opposition gathered strength and Western support diminished. To rally the support of the Kivus’ “indigenous” pop- ulations, he played on anti-Rwandan sentiment. These events likely acted to cement perception of the Banyarwanda and Banyamulenge as foreigners.

In 1995 Zaire’s parliament stripped all people of Rwandan or Burundian descent of their citizenship—including the Banyamulenge—and ordered them to return to their country of origin, wrote René Lemarchand, professor emeritus at the University of Florida, in his book “The Dynamics of Violence in Central Africa”.

Even though the 2004 constitution restored their citizenship as well as that of all groups that fomed part of the DRC at independence in 1960, the Banyamulenge today are still largely without customary land rights. Some Bafuliiru, Babembe, and Bavira—“indigenous” groups in South Kivu—contest the Banyamulenge’s claims that their ancestral village is Mulenge. They claim the Bafuliiru were already living in this area when the pastoralists arrived, according to a 2011 report researched and written by three DRC NGOs and the Life & Peace Institute, a non-profit Sweden-based conflict management group.

In South Kivu’s Fizi and Uvira territories, as in other areas of eastern Congo, conflicts are both highly localised and affected by regional and national politics, according to Séverine Autesserre, a political science professor at Columbia University. For example, disputes related to land management and transhumance (mass movement of people with their animals) in South Kivu often drive the conflicts, she writes in her book “The Trouble with the Congo”. Farmers accuse the pastoralists of allowing their cattle to trample or eat their crops. The pastoralists are angered by the extra-legal taxes that armed local “self-defence” groups demand; and some now carry arms. The first clashes between armed Banyamulenge and Bafuliiru took place in September 2008 in Minembwe in South Kivu, according to the 2011 NGO report.

Politicians prey on these ethnic divisions, according to Koen Vlassenroot in a study published in 2002 by the Review of African Political Economy. Some even have direct links to armed groups, according to the findings of a November 2013 conference held in Kinshasa, the DRC’s capital, co-organised by the Rift Valley Institute, a regional think-tank, and others.

This author conducted 52 interviews in South Kivu from September to December 2013 with Congolese administrators, army personnel, NGO workers, peace activists and researchers. Many cited poverty, a lack of education and fear that another ethnic group might harm them as reasons to join an armed group.

What should be done? How can this very mixed-up history of migration and nationality be addressed to reduce tension? The DRC remains unstable and has not established institutions that provide sufficient security or justice. Another major problem is that the communities are often isolated and their contact with each other is infrequent. Some people have to travel for three or four hours on very rough roads to get to the nearest local market. They simply do not know or trust each other.

A glimmer of hope is emerging, however. Local conflict has been dealt with relatively successfully in some areas of South Kivu’s Fizi and Uvira territories through permanent structures where residents can resolve their differences. Three local NGOs— Action for Endogenous Peace and Development, Arche d’Alliance and the Network of Organisational Innovation—spent three years negotiating with leaders of the Bafuliiru, Babembe, Bavira and Banyamulenge communities.

First, they identified the often contradictory concerns of customary authorities, community leaders, activists and others through a series of intra-community negotiations and developed a unified position. This led to the first Inter-Community Dialogue in Bukavu in 2010. At this five-day workshop in March 2010, the communities agreed to establish permanent structures that became known as Inter-community Dialogue Frameworks (Cadres de Concertation Intercommunautaire or CCIs in French). They also set up mixed committees of pastoralists and farmers.

The CCIs do not perform miracles: they are not always successful in stopping violence; and sometimes ethnic posturing plays out at the expense of constructive dialogue. But these structures have helped to ease tensions.

Some of the most positive CCI developments have been transhumance accords, which set out the terms for the seasonal migration of cattle through farmlands. These agreements specify that the communities will agree on the site of the cattle’s corrals, watering spots and their routes. In Uvira, these paths are now clearly marked with road signs. These accords also lay out the terms for the payment of tribute by pastoralists if they pass through the land of another group, usually a gift of livestock. The Uvira agreement called for a case of beer.

If the DRC government is truly committed to unwinding the ethnic tension and conflict in the Kivus and other provinces, it needs to support more grassroots initiatives like the CCIs. These mediations have succeeded because the communities established, manage and have a stake in them. Supporting local initiatives means giving communities, including local or provincial government authorities, the space to engineer these projects themselves, without direction from a central authority far away in Kinshasa.

At the same time, however, the government needs to strengthen its national and local institutions to guarantee accountability, justice and security. A first step would be to establish a clear and fair citizenship law.