North Africa: complementary tones

The region’s cash-heavy countries could harmonise with its productive economies

The countries of north Africa trade less with each other, and invest less in each other’s economies than any other region in the world, according to a 2012 African Development Bank report.

From Morocco to Egypt, the region’s economies are still battling high unemployment and stagnant growth, factors that led to the Arab spring rebellions beginning in 2010. Their non-cooperation is ruinous because they could help each other to prosper. The region is conveniently split between the cash-heavy, non-productive economies of Algeria and Libya and industrious, but cash-poor Tunisia, Morocco and Egypt. The former have too much liquidity; the latter are desperate for investment.

A 2011 study carried out by Harvard and MIT ranked 128 of the world’s economies in terms of the diversity of goods exported, an indication of a country’s productivity. Egypt, Morocco and Tunisia ranked 62nd, 83rd and 47th respectively, with leading exports of machinery, textiles, chemicals, vegetables and petroleum products. These three countries are among the most diverse in the region.

Egypt, Morocco and Tunisia have promising financial infrastructure—such as stock markets and banks—but sometimes lack cash to invest through these channels. Nearly 11% of bank loans in Egypt are not generating returns, compared with the average of 3% for middle-income countries, according to 2012 World Bank figures. Additionally, the total value of the Egyptian stock market amounts to only 22% of GDP, compared with an average of 50% for middle-income countries. This suggests that the banks and the stock market need additional capital.

Algeria and Libya, on the other hand, have less productive economies but money to invest—explained by their oil and natural gas exports. Algeria and Libya ranked lowly, 115th and 119th, on the Harvard/MIT economic diversity ranking. Yet Algeria’s GDP per capita, at $5,400, is $2,000 higher than that of Egypt. Total savings in Algeria is 48% of GDP, which exceeds the average 31% for middle-income countries and dwarfs Egypt’s 13%. While these countries lack the financial infrastructure of Egypt or Tunisia, they have money to invest elsewhere.

This non-cooperation and division is pricey, costing up to 3% of regional GDP every year, according to a 2012 estimate by the Moroccan ministry of finance.

Potential for collaboration is evident across sectors. These north African countries do not share their energy. For example, Egypt, Morocco and Tunisia import oil and gas mostly from Central Asia while Algeria and Libya have significant reserves. Energy experts such as Anthony Patt, of the Austria-based International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, have touted the potential for solar power in the Sahara, linking north African solar farms to markets in Europe and beyond. One planned network of solar plants in north Africa, DESERTEC, hopes to generate more than 125 gigawatts of power, or 15% of Europe’s annual consumption, and to send it through high-voltage cables under the Mediterranean Sea.

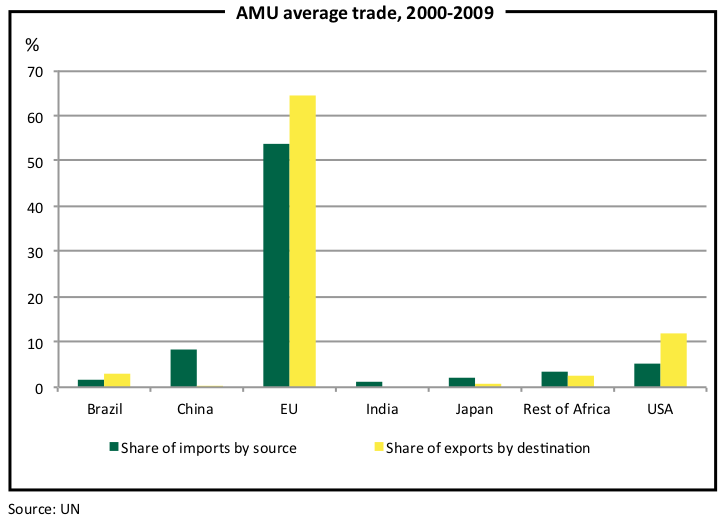

Likewise, the region lacks a common market for information technology (IT) or transportation infrastructure, despite increasing demand and human capital. IT and transportation capacity vary widely throughout the region’s countries. Egypt’s oranges and fertilisers have a difficult time making it to markets in the Maghreb be- cause of its poor roads. North Africa lacks an area-wide telecom company, which can upgrade cellular phone and data networks. Regional integration has clear the- oretical benefits. Economic unions are able to bargain collectively with other associa- tions: the most important in this case would be the European Union (EU), the region’s largest trading partner. Integrated markets also have a higher tolerance for financial shocks than individual economies. Most im- portantly, markets expand when economic policies work together and states lower barriers to trade and investment.

Yet regional integration also has potential downsides. First, more expensive products from partner countries may replace lower-cost products once purchased from non-members. Additionally, state revenues are decreased when tariffs are reduced. The flight of capital—financial or human—could disproportionately hurt poorer states. But these downsides are manageable, and acceptable when compared with the benefits.

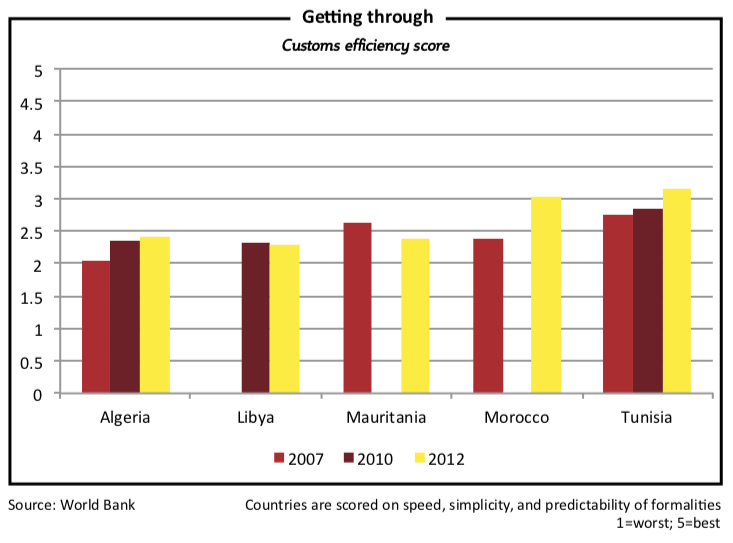

Deeper economic cooperation requires significant work and government political will. Many of these countries have inward-facing economies and incompatible trade, investment and financial regulations.

The problem of currency conversion is a good example. Tunisian law prevents trading the dinar on international markets and prohibits the import or export of the cur- rency. The government adopted the non-convertibility policy to control inflation, but it hurts entrepreneurs and limits Tunisia’s role as a potential financial hub for the region.

These exchange limitations frustrate Tunisian business, according to Bassem Bouguerra, a Tunis-based entrepreneur and founder of the advocacy group Tunisian Institutional Reform. Tunisians have limited access to buy and sell in foreign markets because bank transfers and the use of credit cards are restricted, he says. Businesses cannot buy ads on Facebook or Google and cannot sell apps on iTunes; consumers cannot use Amazon or eBay, or buy plane tickets online.

In turn, Tunisian businesses cannot offer these services to foreign customers. “Tunisian software developers and entrepreneurs say that they cannot build products here since monetisation of IT products is virtually impossible,” Mr Bouguerra says. “They say that they will try to leave the country to launch their products elsewhere.”

Regional integration has been tried before, but failed. The Arab Maghreb Union (AMU), a trade union founded in 1989, includes Algeria, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco and Tunisia. Rivalries between member states, mainly between Morocco and Algeria over the disputed Western Sahara, have rendered the AMU largely ineffectual.

Poor implementation of the Greater Arab Free Trade Agreement (GAFTA), a project of the 22-member Arab League, means it has little effect in the region. Regulatory restrictions on the movement of goods and investments have counteracted GAFTA’s most important contribution: reducing the region’s tariffs. Violent instability in Libya and Algeria has also scared off investors and trading partners. The closure of the Morocco–Algerian border in 1994 has hindered the movement of people and goods.

The foundations for cooperation exist, but need to be expanded and applied more effectively. Gains from trade liberalisation in north Africa, through organisations such as GAFTA, could approach $350m in 2015, according to a 2012 UN Economic Commission for Africa report.

Some progress is underway. Libya’s direct investment in Morocco, mainly in real estate, has spiked since 2011, according to officials who did not provide numbers during a joint economic summit in Casablanca last March. Bilateral trade has also increased and in 2013 exceeded $110m, according to the Moroccan trade minister. Libya could benefit from Morocco’s expertise in infrastructure, agribusiness and industry. The Moroccan trade minister touted regional integration as a “strategic” way to “create suitable economic conditions to foster shared wealth”.

Economic policymaking should reflect the advantages of free movement of people between north African countries. For example, governments could launch university-exchange programmes with foreign students to boost the comparative advantages of the region’s universities and schools, such as Tunisia’s excellent vocational institutes. Trade delegations could also make investors more aware of opportunities in neighbouring countries.

Some north African countries prefer partnering with other regional unions, without realising the added benefits that a united front could present. Egypt, Morocco and Tunisia have signed bilateral agreements with the EU to improve financial and regulatory standards with the promise of trade privileges. They might have negotiated better terms as an economic union than an individual country.

Current prospects for integration are unclear, given the region’s political instability. The revolutions that swept north Africa in 2011 might make governments more cautious and inward-looking in the interest of stability. But the nationalist themes of the Arab spring could also inspire policymakers to address economic grievances through creative solutions, such as a unified region.

A consolidated north Africa could also serve as a crucial link between Europe and emerging sectors in sub-Saharan Africa, such as energy, transportation, IT and resource extraction. European firms are increasingly looking for new opportunities on the continent. North Africa could be the gateway.