Graft in Mali

New government fails to reverse entrenched corruption in the public and private spheres

Blue-clad traffic police officers have their hands full dealing with offending cars and motorbikes on the choked streets of Bamako, Mali’s capital. Their back pockets are full too, because they use the highway code as a price list for bribes: 500 CFA francs ($1) for a broken indicator light, 3,000 CFA francs ($6) for a fake or missing driving licence. Moneyed officialdom is elsewhere, too: during the November 2013 parliamentary elections, party agents openly distributed 5,000 CFA franc ($10) notes to voters at polling stations. Local journalists who turned up for the press conferences of the National Independent Election Commission each received 15,000 CFA francs ($30) in “expenses”.

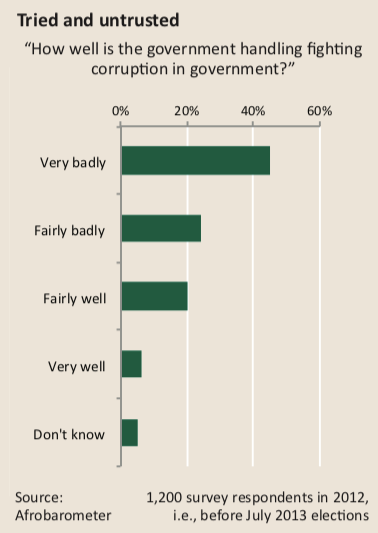

This is known as getting by à la malienne (Malian style), a practice that taints almost every sphere of life in this impoverished west African nation. The country’s new president, Ibrahim Boubacar Keita, elected in August 2013 with a strong mandate, has done very little to tackle the corruption that precipitated the March 2012 coup.

Mali remains institutionally crippled. Despite opening a round of talks with northern rebels in Algiers in July, the government looks incapable of building on the opportunity for peacethat was provided when France in January 2013 sent up to 4,500 troops who were joined by 10,000 United Nations peacekeepers. The various actors who had made Mali ungovernable in the run-up to the coup and its aftermath—local and national government officials, traffickers, religious extremists, separatists and branches of the military at war with each other—have clawed back their fiefdoms of power and influence. The north—with the exception of Timbuktu and Gao where the UN and French troops have firm bases—has once again been abandoned by Mali’s army to become a battlefield for desert mercenaries with allegiances that shift like dunes in a sandstorm.

“The Europeans let this happen,” said a veteran west African diplomat in Bamako. “They were fooled by the seeming ease with which the French ousted the Islamists in January last year. They rushed to sign a big cheque so elections would be held. But the staging of democratic elections alone was never going to be enough to undo a stratified society with endemic corruption, weak institutions, little in the way of a civil society and no living memory of responsible governance.”

So ingrained is criminality in the public sphere that the parastatal power provider, Eléctricité du Mali (EDM), runs its generator in the northern town of Kidal with stolen Algerian fuel bought from smugglers. “If you want to know why we do it à la malienne in Kidal, just look at the map,” said EDM spokesman Thiona Mathieu Koné. “The north is completely under-developed. It takes more than a week to drive a truck from Bamako to Kidal. It is much cheaper to buy Algerian diesel informally than to transport the fuel all the way from the capital. After all, we are under pressure to run a tight ship!”

One of the world’s poorest countries, Mali sorely needs foreign investment. But apart from French oil company Total and two mining concerns—South African-based AngloGold Ashanti and UK-based Randgold Resources—the established names in African investment are not interested in Mali. There is easier, cleaner money to be made elsewhere.

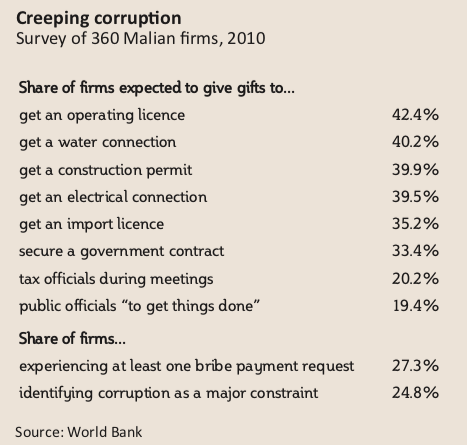

“Doing business in Mali demands a particular approach,’’ said Facinet Coulibaly, general manager of Macrowaste, a new garbage collection company in Bamako. “If you want a permit or licence to operate, you do not just wait in line. You do the same thing as when you go to the hospital: you buy a place at the front of the queue. When our internet goes down, I do not simply wait for our provider to send a technician. That takes days. I have to privately pay the provider’s technician to put me at the top of his call-out docket.”

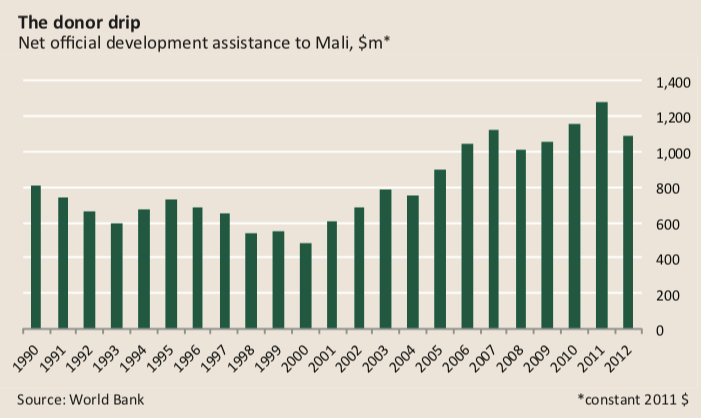

Given that Mali, with its high poverty rates, is on a permanent donor drip, corruption is also ingrained in the aid sector. A 45-year-old Malian employee of an international aid agency recalls how a mayor in the Goundam region of northern Mali defrauded five donors at a stroke: “He told each of them he needed a borehole,” said the aid worker, who requested anonymity. “He then helped rig each of the five tender processes and chose one company to drill a single well. He had five plaques made, each featuring a different donor’s name. I worked out what he had done after I was invited to attend an unveiling ceremony for a borehole and, a few weeks later, I was invited again, only to find myself at the same well with a different plaque on it.

“This kind of corruption goes on all the time. The largely illiterate population has no idea of the extent of it. There is a lot of fake invoicing. The practices become possible because the staff of the international agencies change all the time. In some cases the foreign agencies do not even care what happens to their money, so long as it is seen to have been spent.”

Damien Helly, deputy programme manager of the European Centre for Development Policy Management, a think-tank based in The Hague, confirmed the complicity of international donors in aiding and abetting corruption: “Often for very bureaucratic or political reasons, many aid agencies are under pressure from their headquarters to disburse available funds. The host country representatives know that very well,” he said.

Occasionally, someone blows a whistle. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) went public in May with its concerns over the purchase by Mali of a second presidential jet for around $40m and a government guarantee of $200m for defence equipment. Neither item had been submitted to parliament or to a tender process, prompting the IMF to delay paying a $5.3m tranche of budgetary support.

Despite Mali’s blatant levels of corruption, the international community continues to nurse the pipe dream that Mr Keita’s government will broker an equitable peace deal with the Tuareg secessionists, have the credibility to bring trafficking to heel, de- centralise government and develop the north. He will not and possibly cannot because the parallel economy reaches deep into every sphere and is controlled by people who would lose out financially under any other arrangement.

The outlook is bleak but it is not as desperate as it was in 2012. It is unlikely that the UN, with its considerable peacekeeping commitment, or France, which still has 1,700 troops in the country, will allow Mali to slip back into the governance void that saw al-Qaeda and the Tuareg secessionists march to within a day’s drive of Bamako in January 2013.

The graft is somewhat reduced compared to 2009, when military and government officials, apparently in the pay of South American drug lords, allowed a Boeing 727 laden with an estimated 10 tonnes of cocaine to land in the desert near Gao.

In June Jacqueline Togola, Mali’s education minister, pulled the plug on a network of fraudsters who reportedly sold sets of exam questions for 300,000 CFA francs ($600) to parents at private and state schools. The case has not yet come to court but police have arrested at least 16 people, several of them employees of the education ministry, according to media reports.

The minister’s clampdown— which saw officials spend 48 hours without sleep as they changed all the 2014 baccalauréat questions— was aimed at restoring long-lost credibility to the country’s most senior school exam. This was a bold and rare signal to the international community that Mr Keita’s government is tackling corruption.

The government needs to keep the aid taps open. After the March 2012 coup, the EU and the Obama administration suspended development aid to Mali. The EU suspended the $794m in development aid it had allocated for the 2008-2013 period, according to EU press releases, while the Obama administration terminated ahead of schedule its $460m compact with the country, according to the US State Department. Aid began flowing back last year: the EU resumed development funding in February 2013, the US in September.

Whatever Mr Keita’s intentions, his efforts have not been enough to convince the international community that his government is committed to transparency. When the IMF postponed its review of Mali in July—citing concerns over management of public funds—all other donors paying direct budgetary support delayed their disbursements.

With development agency funds comprising 25% of the treasury’s total income, the frozen $280m of payments—from the EU, the World Bank, the African Development Bank, Denmark and France—represented a sharp warning. Whether this suspension will cramp the “Malian style” of the country’s leaders remains to be seen.