Democratic Republic of Congo

Unsubstantiated claims distract from the real issues facing DRC agriculture

Perhaps it is the size of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) or its strife-torn history that fires the imagination, but people seem to believe any statistical claim made about the central African country.

Take for example the assertion, in former US vice-president Al Gore’s latest bestseller, “The Future”, that 48% of the DRC’s cultivable land has been sold to foreign investors. The claim was repeated as recently as July in the pages of Le Potentiel, a DRC newspaper.

Yet there is no evidence to support the claim. The US-based Rights and Resources Initiative (RRI)—the organisation Mr Gore cited—said it “cannot speak to the scale” of land acquisitions in DRC. Another advocacy group, the Catholic Committee against Hunger and for Development, said it is “not seeing a land rush in DRC”, where foreign investments are “timid and hard to identify”.

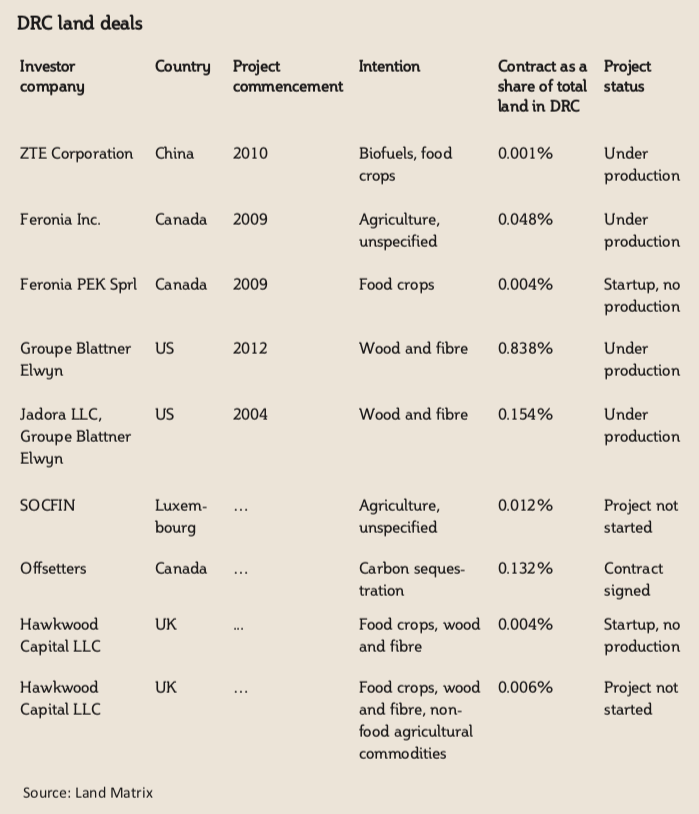

While the DRC’s forestry concessions to foreigners are considerable, the same is not true of agricultural land, according to the International Land Coalition (ILC), a Rome-based alliance of 152 civil society and inter-governmental organisations. To date the coalition has documented only 258,565 hectares of land concessions to foreign agri-business investors out of 120m arable hectares in the country.

A wave of acquisitions is under way, but buyers are usually domestic investors, said Etienne Bisimwa of Congo’s National Confederation of Agricultural Producers. Many have been speculative investments anticipating demand for biofuels and most, about 2,000, “are not being farmed,” he said.

Investors interested in DRC real estate face an array of obstacles: lack of infrastructure and access, in addition to political and security risks, as mining companies have found out. Executives from 742 mining firms ranked DRC third last—after Indonesia and Vietnam—out of 96 jurisdictions for “exploration investment favourability”, according to a 2013 survey by the Fraser Institute, a Canadian think-tank.

Agricultural investors face particular constraints arising from the country’s land tenure regimes: notably a clause in the 2011 agricultural law that limits foreigners to a 49% stake in new agricultural investments, as well as a lack of legal clarity around customary or community land rights.

The government acknowledges problems with its land tenure regime and is considering easing the 49% restriction, said Simplex Malembe, chair of a government sub-committee on land tenure. Smallholder organisations insist that if foreigners are allowed to own a 50% stake or higher in new agricultural investments, the government should also give more legal recognition to customary land rights, he said.

A 1973 law permits traditional chiefs to continue allocating land. It specifies that these rights will be further defined by a presidential ordinance that has never been issued. But delineating customary land rights will be difficult, as customs vary widely across the DRC, said Albert Paka, deputy cabinet director at the land affairs ministry. “In some parts of the country land belongs to the chiefs, whereas in other parts it belongs to the community and the chiefs are merely arbiters of land rights,” he explained.

Lack of agreement on community land rights poses special risks for large-scale agribusiness investors, whose area of operation would be much greater than for most mining companies, thereby increasing the risk of disputes with potentially resentful neighbours.

African countries where community land rights are formalised in law—such as Ghana, Liberia and Tanzania—have attracted more agribusiness investment relative to their size than countries with weaker community land rights, according to a 2013 RRI report and the ILC’s online database.

While land law reform proceeds slowly in most African countries, the DRC’s goals to increase agricultural investment and domestic food production may hasten decision-making around land tenure.

The prime minister’s office has a plan to create some 20 “agro-industrial parks”, ranging from 40,000 hectares to more than 100,000 hectares, which will be leased to investors and used to produce food for the domestic market.

In July DRC President Joseph Kabila opened the first, at Bukanga Lonzo, about 200km east of Kinshasa, the capital. The government has allocated $83m for spending on roads, electricity and other infrastructure to service the 70,000-hectare park, according to reports from Radio Okapi, a UN-backed radio station. Local farmers are not allowed inside the park, Mr Malembe said.

Mr Malembe’s sub-committee is currently consulting community representatives, chiefs, indigenous people and others who may be affected by these parks. Their views could inform a “transitional” land rights decree to be issued by the prime minister.

The agro-industrial parks are an unprecedented commitment to agriculture by a DRC government, Mr Malembe said, but warned that the consent of local communities would be necessary to prevent disputes. One of the most pressing questions is how communities will be compensated for land taken by a park. “There is not a clear link between compensation for the chief and for the community,” he said. Mr Malembe is also concerned that smallholders could face an uncertain future it they were not included in opportunities to produce for the market.

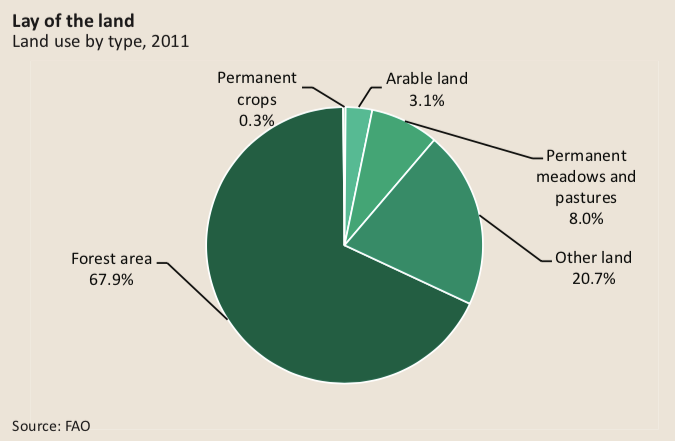

Only 10 % of DRC’s arable land is used for agriculture, John Ulimwengu wrote last year in an article published on the website of Engagement Global, a German consultancy. This abundance of underutilised land in the DRC means demands for jobs or economic opportunities from communities neighbouring the agro-industrial parks may be underwhelming. But in the densely populated Kivu provinces in the east, where land shortages have long been a cause of conflict, those demands could pose a more serious problem.

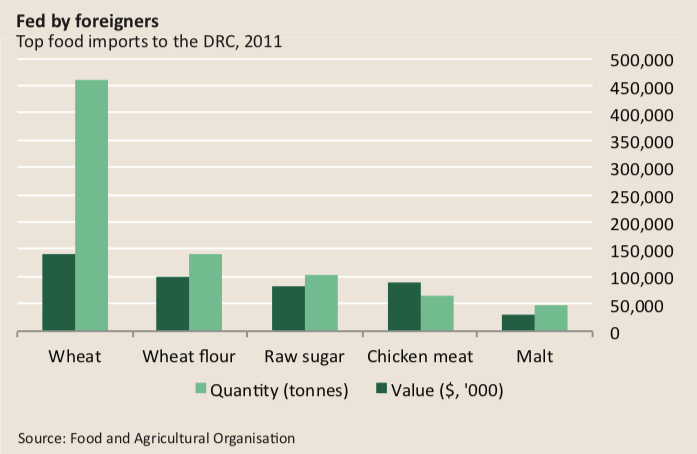

Few other African countries have opted for national agricultural plans that so clearly favour large-scale commercial farming for the domestic market. Mr Ulimwengu, the prime minister’s agricultural adviser and a former research fellow with the International Food Policy Research Institute, a think-tank, says large-scale agriculture should significantly reduce the country’s bill for imported food.

The parks could also enhance economic opportunities for small-scale farmers. If these commercial operations adopt labour-intensive market gardening, for instance, locals could work as employees or contract farmers. Another boon may be improved roads that bring in agronomists, vets, trucks, tractors, silos, fertilisers and improved seeds, said one agricultural consultant who wished to remain anonymous. “The little guy gets pushed out of marketing grains, but would now have a means of getting fruit and vegetables and specialty items to a larger market,” he suggested.

To help the DRC’s smallholders, land rights advocates should focus on land-use planning instead of unsubstantiated claims about foreign land grabs. This requires researching the effects of land-use changes on local markets. Michael Richards, economist and author of the 2013 RRI report, said too few studies of this kind have been undertaken in west and central Africa and the need for them is “urgent”.