Zambia: public order

The government uses a colonial-era law to control and confine opposition parties

With the death in late October of Michael Sata, Zambia’s president, opposition parties in Africa’s largest copper-producing country may find their political space a bit wider.

Mr Sata, 77, died in London on October 28th where he was receiving treatment for an undisclosed illness. There had been much speculation during the year about Mr Sata’s health. He had been out of public view for three months during mid-2014, resurfaced in September to open Parliament, but then missed Zambia’s celebrations on October 24th to mark 50 years of independence from Britain.

Now a succession battle looms ahead of the presidential by-election which must be held within 90 days, according to the constitution. An obvious heir to Mr Sata’s Patriotic Front (PF) party has not emerged despite much jostling during the late president’s prolonged absences. In the interim, the vice-president, Guy Scott, has taken over, making him sub-Saharan Africa’s first white head of state since FW de Klerk in 1994.

In the interim, the vice-president, Guy Scott, has taken over. Under the current constitution, Mr Scott cannot stand as the PF’s presidential candidate in the upcoming election because his parents are not Zambian or of Zambian descent. The constitution would need to be amended if he were to stand. Such a change would have to be passed through the National Assembly, which, although unlikely, is not impossible in the next three months. Mr Scott is popular with the public even though he is white. He is often described as being “more Zambian” than most Zambians.

As this magazine was going to press, Mr Scott fired Mr Lungu as the PF’s secre- tary-general and then reinstated him the next day after Mr Lungu’s dismissal triggered riots in Lusaka, the capital. Mr Lungu remains the defence and justice minister. Some political observers speculated that his removal reflected political manoeuvring among party factions before the upcoming election.

Whatever happens, observers will follow closely the interim government’s ac- tions. Prior to Mr Sata’s death, the opposition had accused the ruling party of intimida- tion and harassment, as well as denying free assembly and other constitutional rights.

In particular, opposition leaders had pointed to what they described as repeated abuse of the Public Order Act (POA). Critics, who include not just the opposition but civil society and human rights groups, claimed the government was using the law to stop campaigning by opposition parties.

Police often used the act to deny permission to meet on the grounds of inadequate staff, “after which police responded in force at rallies to arrest opposition leaders and their supporters”, according to the US State Department’s “Zambia 2013 Human Rights Report”. In contrast, PF supporters, who were sometimes armed, often held rallies without submitting prior notification, with little police interference, the report said.

The POA is a legacy of Britain, which ruled Zambia when it was called Northern Rhodesia until independence in 1964. Written in the 1950s, the law stipulates that individuals must notify the police at least seven days in advance if they wish to hold a public meeting.

A later clause allows for the arrest and imprisonment of those taking part in a public meeting that does not have a permit—which is confusing since there is no earlier mention of the need for a permit.

This and other inconsistencies make the POA “an outcast in a democratic society”, said McDonald Chipenzi, executive director of the Foundation for Democratic Process, an NGO based in Lusaka. “The POA has been used to…deny political parties the right to canvass for support ahead of any electoral contest,” he added.

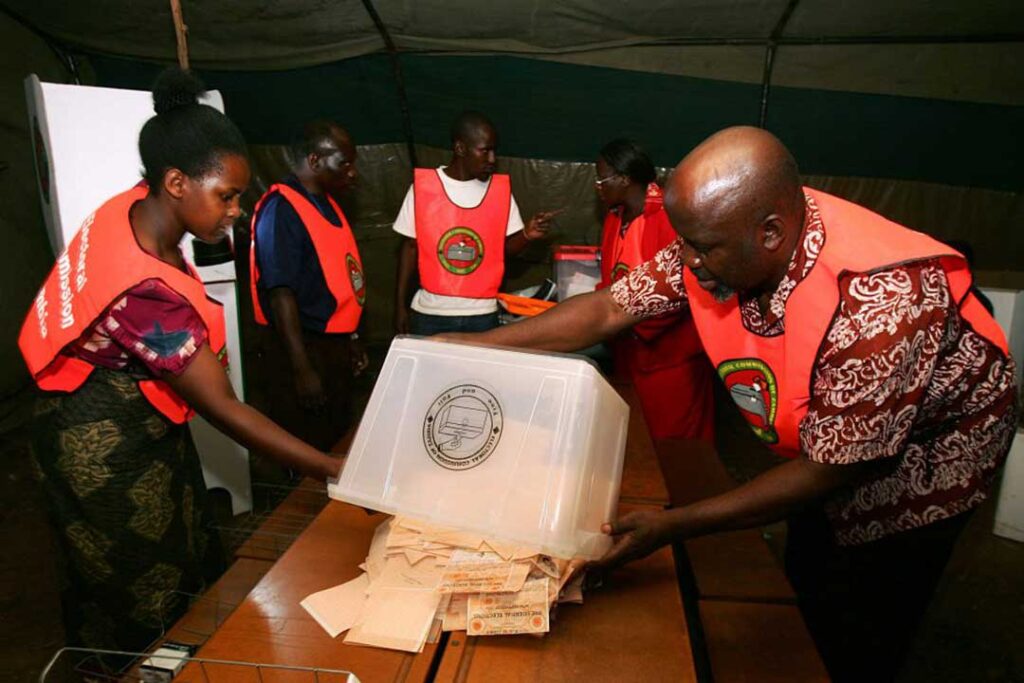

Use of the law to prevent campaigning by opposition parties has become a particularly sensitive issue in light of the unusually high number of by-elections held since the PF came into power in 2011. In the last three years, 22 parliamentary by-elections and over 100 local government elections have been held at an average cost of 3.5m kwacha ($550,000) for each, according to Zambia’s electoral commission.

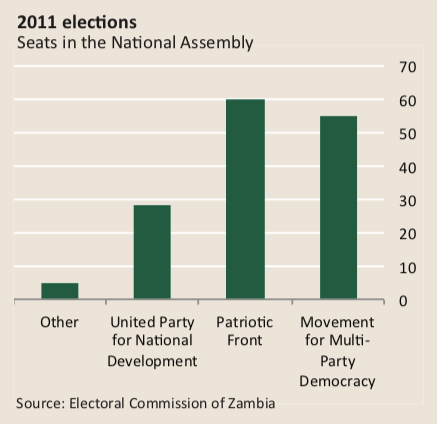

Observers blame the PF’s failure to secure a majority in the National Assembly after the 2011 election for this glut. Mr Sata and his PF only narrowly defeated the former ruling party, the Movement for Multi-Party Democracy (MMD), winning 60 seats to the MMD’s 55. The United Party for National Development (UPND) won 28 seats, independent candidates three. The Forum for Democracy and Development and the Alliance for Democracy and Development won a seat each.

Hakainde Hichilema, UPND leader, has blamed the government’s abuse of the POA for creating an uneven playing field. “How can we enthuse voters if we are not allowed to campaign?” he asked.

Mr Hichilema’s UPND, which envisages a strong economy and vibrant private sector as a foundation for tackling poverty and unemployment, came third in the 2011 poll. Since then, perception has been growing that the UPND is gaining ground. The party has won several new seats in Parliament through by-elections, while the MMD, the largest opposition party, has lost seats.Amid growing public disillusionment with the PF’s apparent failure to meet certain election promises, such as a new constitution, observers see Mr Hichilema as a contender in the next election.

This may partly explain why Mr Hichilema says the ruling party has persistently targeted him. The opposition leader says the police has detained him on numerous occasions—for offences ranging from defaming the president to instigating violence—and disrupted UPND rallies and meetings. “This is the first regime in which we have seen a clear manifestation of a desire by the ruling party to wipe out the opposition,” he says.

The UPND is not alone. MMD leader Nevers Mumba can also readily recount several incidents in which he has been detained under the POA. Mr Mumba, a former vice-president, was elected MMD leader shortly after its defeat under Rupiah Banda in 2011.

In one episode in December 2012 police arrested Mr Mumba and a delegation of 15 MMD members while they were paying a courtesy call to Chief Nkana on the Copperbelt, a competitive electoral patch in central northern Zambia. When the group left the meeting , Mr Mumba says, armed police accused them of holding a meeting without a permit, arrested them and detained them overnight.

Mr Mumba says this is just one of many occasions where the police has disrupted public or, in this case, private MMD meetings.

Government denies that the police has arrested opposition MPs for failing to produce a permit at meetings. It argues that only those holding a public meeting without prior notification have been detained, or those who have defied the police by holding rallies even after they were denied permits because of insufficient police personnel.

Stephen Kampyongo, deputy minister of home affairs, says the POA is the only legislation available that allows government to “manage tensions between freedom and order”. He claims that opposition parties have had “equal opportunities to participate in political campaigning”. He points to their several by-election victories since 2011 as evidence.

The media is another space in which opposition parties are struggling to find a voice.

The government owns two of the four main dailies, The Daily Mailand Times of Zambia. ZNBC, the radio station with the widest national coverage, is also state-run.

Meanwhile, many consider the privately-owned Postnewspaper as pro-government because of its strong support for the PF in the 2011 campaign. The paper’s support was apparently rewarded when several members of its editorial team were elevated to government positions shortly after the election.

“The public media is highly skewed towards government,” says Edith Nawakwi, leader of opposition party the Forum for Democracy and Development and a former finance minister when the MMD was in power. “Even if someone in the ruling party sneezes in an extreme way they will report on that.” In contrast, opposition parties often find it difficult to get column inches unless it suits the media’s editorial agenda, she says.

Opposition parties, however, have access to alternative media outlets. Zambian news websites and blogs have proliferated in recent years. Although the accuracy of their content is sometimes questionable, they offer opposition parties a platform. Facebook and community radio stations offer other outlets.

Now that a presidential election is imminent, the parties will have to address the country’s problems. Although GDP growth has averaged around 7% over the last five years, some 60% of Zambians still live below the poverty line, according to World Bank figures. Poverty is particularly acute in rural areas.

Unemployment also remains high, especially in the formal sector where around 900,000 people have jobs, according to the central statistics office. With nearly half of Zambia’s 15m-strong population under 18, pressure on the country’s limited job market will grow massively in coming years.

Both of these issues are likely to be at the forefront of campaign efforts by all parties in the run up to the presidential by-election which promises to be another close-fought tussle. Whether the PF will open itself up to a fair fight remains to be seen.