Youth in Botswana, under the age of 35, make up over 60% of the population. However, despite this, young people eligible to vote, especially between the ages of 18 and 25, had one of the lowest voter turnout rates in the country’s 2019 general election. While this statistic highlights a growing trend of youth voter apathy across the African continent, it has created the perception that youth are apolitical and “disinterested” in politics.

Political participation, however, goes beyond voting; and low voter turnout amongst youth does not, on its own, make one wholly apolitical. This raises an interesting question about whether young people are wholly apolitical or if they are simply not voting.

Democracy requires citizens to participate, not only to influence public policy but also to ensure that there is transparency and accountability for political leaders and parties. This participation can take the form of more formal types of political engagement such as voting in elections, joining political parties or running for local council, as well as informal forms of political participation such as collective action and advocacy.

Due to the wide range of activities encompassing political participation, it can be quite difficult to define. However, almost all political scientists agree that participation is a key component of any healthy democracy, as it is closely associated with several democratic principles such as freedom of expression and freedom of assembly.

In recent years, youth political participation has become a key focus, emphasising the need and importance for young people to engage and be included in civic activities. One of the key reasons this has been under the spotlight in recent years is because there has been a social shift in how youth are perceived. In many societies, young people have been excluded from participating in civic activities because the assumption is that young people do not know enough.

However, this perception is misplaced, as young people have generally been relatively active in collective political movements. Thus, with the greater attention brought to these movements through media and social media, societies are beginning to acknowledge youth as a political group, emphasising the need for youth political participation beyond protests and collective action.

Encouraging political participation among youth is also important for instilling a culture of civic duty. The assumption around political participation in the past has been that it comes naturally to people, and the youth are just not that interested in politics. However, studies have shown that promoting a culture of political participation helps ensure that democracy is not undermined and those in power are held to account.

Botswana is one of the longest-uninterrupted democracies in Africa; it became a democracy in 1966 following its independence from British colonial rule. Botswana is a parliamentary republic with a multiparty electoral system. Since 1966, they have had 12 general elections, with the most recent one held in 2019. Voter turnout in Botswana has been relatively high since the 1980s. The latest national election in 2019 saw just over 83% of registered voters turn out to vote. This voter turnout is one of the highest in the southern African region, beating countries such as South Africa and Namibia. Similarly, when looking at voter turnout as a percentage of the voting-age population, Botswana ranks second in the region with 53%`, beaten only by Namibia at 55%.

However, breaking down the different age categories, there was lower voter turnout amongst eligible youth, particularly within the 18-25 age group, who make up a large percentage of the population in Botswana. While these statistics unsurprising as they follow general patterns of low voter turnout among youth worldwide, they are still concerning given that Botswana has such a high population of young people.

To explore political participation outside of elections, I used Afrobarometer Round 9 survey data. Afrobarometer is an organisation that conducts surveys every few years on issues around democracy, governance and other relevant issues that affect people on the continent. For this article, I used responses to questions from participants in Botswana on political participation. Specifically, I used three core questions: Have you attended a community meeting in the past year; have you gotten together with others to raise an issue in the past year, and have you attended a protest or demonstration in the past year?

For each of these questions, the respondent had a choice of answering: “No, would never do this”, “No, would do if I had the chance”, “Yes, once or twice”, “Yes, several times”, or “Yes, often”. While this does not fully capture political participation as a whole, it does give an idea of how active people are in the civic space.

I also used the age variable to understand the age range of responses. I divided the ages into two groups: youth, which ranged from 18-35 and adults, from age 36 onwards. I defined my youth range as 18-35, because Afrobarometer does not interview anyone under the age of 18.

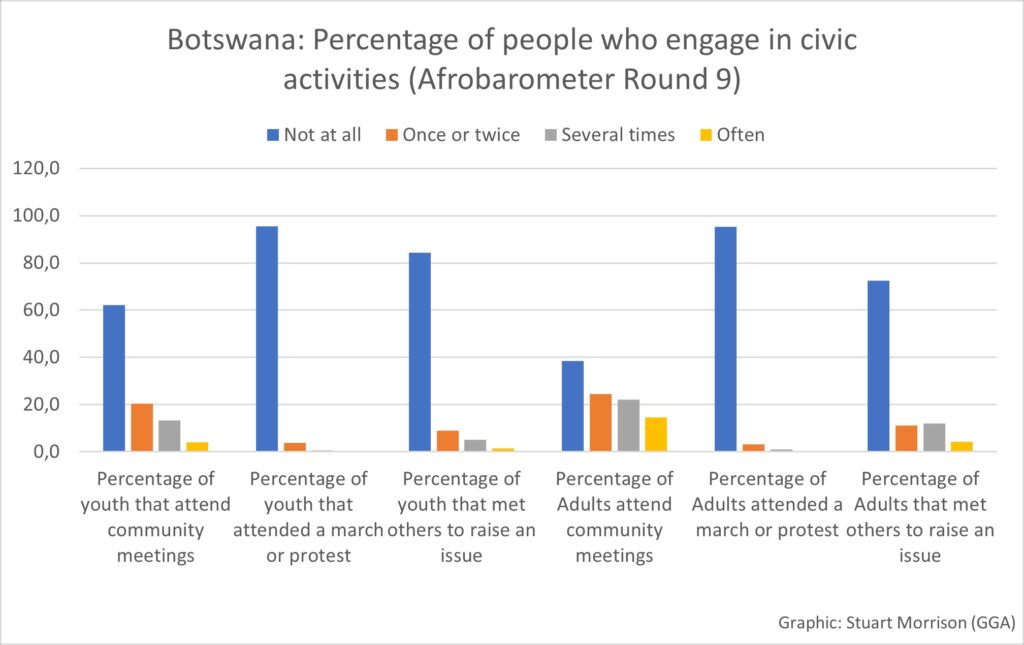

To start with, I wanted to better understand how many youth and adults participated in the civic activities listed. The graph below shows the percentage of people who selected “Not at all”, “Once or twice”, “several times” or “often” to the question of whether they have participated in various civic activities. I combined the “No, would never do this” and “No, would do if I had the chance” responses into one category as I was mostly interested in respondents who were involved in civic activities.

The findings show that political participation across age groups is quite low. This reveals that low political participation in Botswana is not necessarily a youth problem but rather a wider issue of political participation. This supports scholar Adam Mfundisi’s argument that political participation has been an issue since the start of Botswana’s democracy. The fact that there is still quite low political participation as in the 90s, means that there needs to be greater efforts by all sectors of society to promote political participation. However, the question remains: are youth simply apolitical as Graph 1 would seem to suggest?

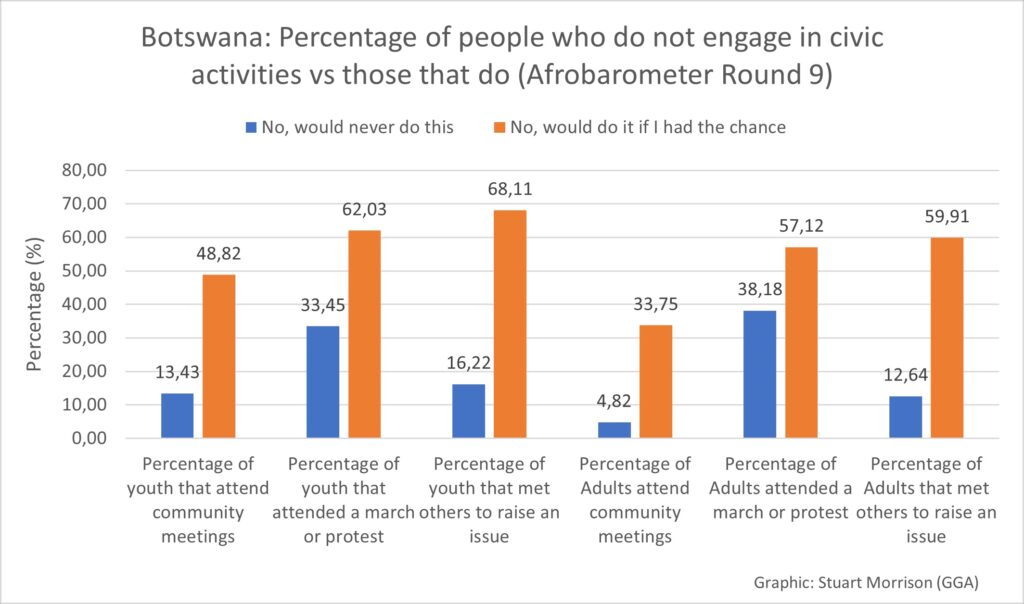

Fortunately, because of how Afrobarometer phrases its questions, it can give a clearer understanding of why people in Botswana are not participating in civic activities. To do this, I looked at the percentage of people who responded “No, would never do this” and, “No, would do if I had the chance”. As shown in the graph below, the majority of people who responded no, followed that up with “would do if I had the chance”, this shows that while there is low political participation rates in Botswana, people would be more active given an opportunity to do so.

Overall, these findings highlight two very important things about political participation in Botswana. Firstly it shows that low political participation in the country is not only a youth issue but something that affects all age groups. This is important as it means that while prioritising political participation among youth is important, policy should ensure that older people are included.

Secondly, it shows that using the term apolitical can be somewhat misleading and reductive as it runs the risk of overlooking the nuances around political participation, as demonstrated with Botswana.

Stuart Morrison is a Data Analyst with the Governance Insights and Analytics team at GGA. His research and expertise mainly focuses on the nexus between local governance, urbanisation and elections. He is currently completing his MA in E-science (Data Science) at the University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, with a background in Political Science, International Relations and Development studies. His multi-disciplinary approach incorporating data science and quantitative methods allows him to provide a nuanced and data-driven approach towards his research and policy work.