There is no doubt that technology is playing a growing role in African politics, including in campaigning and voting. By harnessing the power of big data and social media, politicians and their advisors can target their messages at individual voters. This threatens the democratic process by enabling the spread of inaccurate information, voter manipulation and even hate speech, but a growing number of organisations are now trying to counter these dangers with artificial intelligence (AI) applications.

Platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Twitter provide political parties with new communication channels but also allow bigotry and xenophobia to flourish. Some social media influencers are even paid to post false claims about politicians. For instance, a BBC investigation published in January 2023 identified Nigerian influencers who receive cash, expensive gifts, government contracts and even political jobs in return for false posts.

Social media companies claim that they invest heavily in moderators to check posts, but there is rarely sufficient capacity to cope with the sheer volume of content. Some moderators are based in Africa, but most platforms are based in the US, where few staff have much knowledge of the political context of individual African countries or their incitement laws.

Part of the problem is that almost all social media companies and regulation authorities are located outside Africa, and accountability is difficult when information structures are global. In 2019, the Kenyan political analyst Nanjala Nyabola posed the question in relation to controversial PR agency Cambridge Analytica: “What does accountability for political misinformation look like when a British company uses an American platform to influence political discourse in a Kenyan election?”

There is some concern from the US Department of Homeland Security and NATO among others, over the use of AI to manipulate platform algorithms to promote messages, including using deepfake videos that depict people doing or saying things they did not say or do. However, AI tools can also counter the worst excesses of social media by detecting and combating misinformation because of the massive computing power available, where social media platforms cannot afford – or will not provide – the number of moderators needed.

AI can also encourage people to vote by automating voter registration, with chatbots providing potential voters with information on registration and polling sites. AI predictive analysis can also aid campaigners by identifying probable voters. At the same time, it can detect irregularities in voter registration.

African election results, including in Nigeria, Kenya, and Cote d’Ivoire, have been subject to appeals, with losing candidates and parties petitioning electoral commissions and courts over corruption or irregularities. However, when combined with electronic voting, blockchain-based decentralised ledgers enable real-time tallying and avoid the time-consuming process of transporting ballot boxes for counting. Real-time tallying can also counter ballot stuffing and monitor voter turnout for irregularities to ensure data integrity.

In the longer term, facial recognition could be used to authenticate voter identity, which should prevent some people from casting votes for deceased relatives. In the run-up to the 2022 election, Kenya’s Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) found 246,465 dead voters on its register, as well as 226,143 people registered with ID cards that did not belong to them and 481,711 people with duplicate records.

In Nigeria, the Voter Turnout Project leverages AI to identify unregistered voters and encourage them to participate. Also in Nigeria, an independent fact-checking initiative supported by the United Nations Development Programme called iVerify uses AI to check for election-related misinformation to help voters find trustworthy information. Vote Compass even uses AI to help Nigerian voters decide who to vote for by comparing their views with those of candidates, although there are obvious potential problems with such an approach.

The African Union High-Level Panel on Emerging Technologies (APET) has acknowledged the potential of AI to facilitate free and fair elections across Africa, including how governments engage with voters. An APET report published by NEPAD in October last year said: “AI’s capabilities, including personalised outreach, predictive analysis of voter behaviour, real-time information dissemination, social media sentiment monitoring, targeted voter registration efforts, and the combating of voter suppression, collectively contribute to a more robust and inclusive electoral process.”

AI resources in Africa are limited, so the first ever United Nations General Assembly resolution on AI governance related to Africa. In March this year, the General Assembly unanimously passed the resolution on “Seizing the opportunities of safe, secure, and trustworthy artificial intelligence systems for sustainable development”, which was sponsored by Kenya and the US, among other countries.

The resolution asked the industrialised world to provide African countries with technical and financial assistance to “bridge AI and other digital divides between and within countries and promote safe, secure and trustworthy AI systems to accelerate progress towards the full realisation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development”. It also calls for tools to be developed to detect AI-generated content and for AI developers to test their systems in Africa and other parts of the world before commercially deploying them. However, such resolutions are not legally binding, so it will be interesting to see how much is achieved.

Just like everywhere else in the world, it is vital not only that Kenya’s elections are free and fair but that they are seen to be so. However, Kenya’s needs are compounded by the fact that disputes over recent election results have led to violent attacks, with political divisions often heightened by ethnic divisions. More than 1,200 people were killed in the aftermath of the 2007 election, resulting in political leaders Uhuru Kenyatta and William Ruto being committed to trial by the International Criminal Court, although the cases were later dropped.

Chris Msando, the Kenyan Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC’s) head of information, communication and technology was kidnapped and brutally murdered in the run-up to the country’s 2017 election. Legal cases over hate speech can be long and difficult, so there have been few prosecutions in the country.

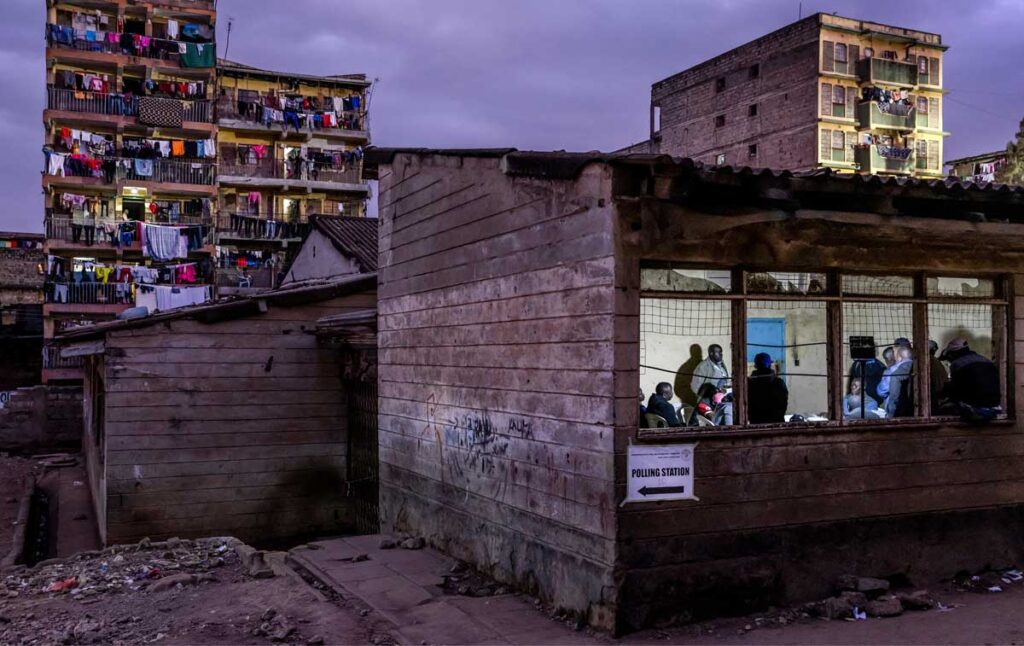

Photo: Luis Tato / AFP

Yet solutions are emerging through Kenya’s technological expertise, with the country well known as a centre of mobile money and mobile banking innovation. The original mobile money service, M-Pesa, now works with the IEBC to allow citizens to register as voters via their phones, while the Election Buddy app provides users with candidate profiles, the location of polling locations, and other election-related material.

As a result of past violence, Kenyan civil society has partnered with tech specialists to use AI to counter hate speech and misinformation. With help from the United Nations Peacebuilding Fund, the MAPEMA (Maintaining Peace through Early Warning, Monitoring and Analysis) consortium of Code for Africa (CfA), Shujaaz and AIfluence used AI and machine learning to identify more than 550,000 toxic posts on Facebook alone in the 2022 Kenyan election. More than 800 of these were flagged and shared with platforms for action.

“Part of our work was to use the expert skill sets that we have in digital forensics and data analytics to monitor social media platforms and digital media for cases of hate speech and incitement and communicate these results to enable effective responses by our partners,” Peter Kimani, a senior CfA investigative data analyst commented. CfA is the continent’s largest network of civic technology and data journalism labs. MAPEMA also took more in-depth data from seven hotspot counties to get more detailed information.

CfA used a range of tools on the project, including a machine-readable database called “hatelex”, Meta’s open-source CrowdTangle, and proprietary solutions like Meltwater to monitor conversations and identify networks involved in electoral disinformation campaigns on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter. It also used media monitoring solution CivicSignal, which contains more than 410 Kenyan digital media collections, and proprietary system PrimerAI to track digital media. Shujaaz used the results of their analysis to produce messaging that was integrated into comic and animated content to counter misinformation.

It will be interesting to see how disinformation and social manipulation on the one hand, and AI monitoring on the other, have progressed by the 2027 Kenyan elections, when there will be 28 million voters. The IEBC should then be able to use AI algorithms to analyse huge amounts of electoral data, including voter registration, polling stations and campaign finance reports, to identify unusual patterns.

“Through continuous innovation and collaboration, Kenya can harness the transformative potential of AI to strengthen its democracy and electoral governance and become the ‘sub-Saharan African hub of democracy’,” wrote Joab Odhiambo, an actuarial science expert at Kenya’s Meru University of Science and Technology, in May 2024 on Kenya’s Citizen Digital platform

This is an optimistic vision, but given the level of concern over social media and tech meddling in elections in Africa and elsewhere, it is vital that voters are educated about the use of AI in elections to instil confidence and build trust in the process.

Dr Neil Alexander Ford has been a freelance consultant and journalist on African affairs for more than two decades. He covers a wide range of topics from international relations and organised crime to cross-border trade and renewable energy. Consultancy clients include international organisations, law firms and financial services companies, and he has acted as an expert witness in Africa-related legal cases. He has a PhD on East Africa’s international boundaries, ranging over the effect on regional economies; cross-border political disputes; and the impact of the boundaries on local communities, such as the Maasai.