Three days a week – Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays – at around 4am, residents of the inner-city suburb of Yeoville in Johannesburg are woken up by the squeaking and rattling of a crudely built cart drawn along their street by a middle-aged man in torn overalls.

This is John*, trudging his way to a dumping site on the outskirts of the suburb, aiming to be the early bird to collect any material that is recyclable. On his way back four hours later, the huge pallet cart is loaded with sacks, each packed with anything plastic.

This is how John ekes out a living on the dog-eat-dog streets of Johannesburg – collecting recyclable materials – from empty plastic bottles, containers, bags to milk cartons – he can sell to waste recycle businesses, bringing to truth the old adage, “one man’s waste is another’s treasure”.

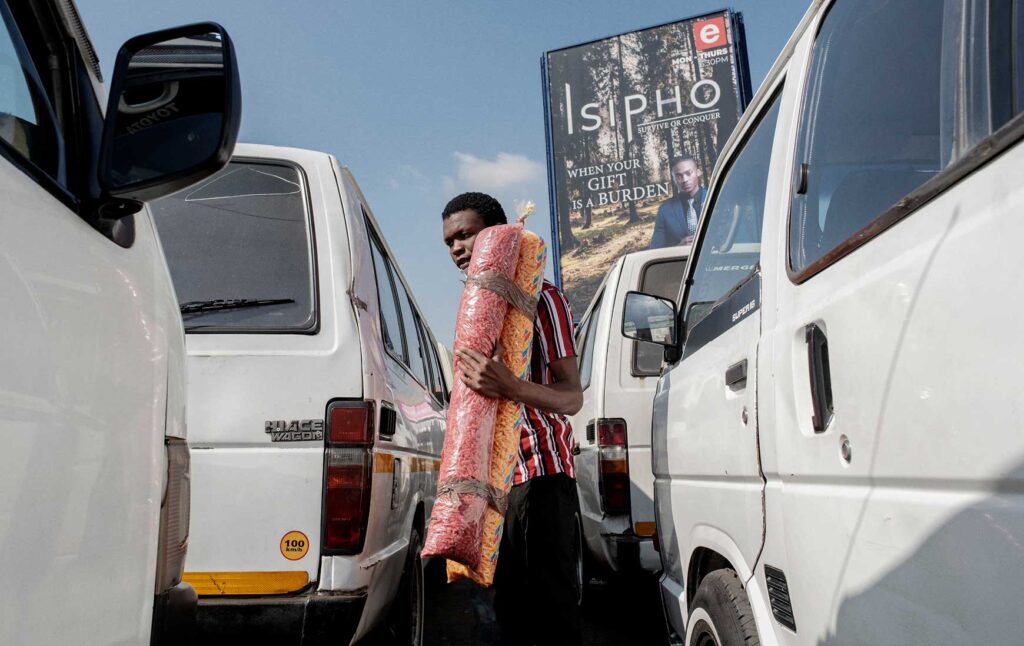

John is part of Johannesburg’s large informal trading sector, which includes street vendors who sell almost everything from fruit and vegetables to food, clothing, and single cigarettes. These vendors operate mainly in the inner city, commonly referred to as the central business district (CBD).

Studies have shown that, although unregulated – and due to South Africa’s fast-growing unemployment rate (which stood at 32.1% by the third quarter of last year) the informal economy is rapidly growing. The country’s statistical service, StatsSA, has noted that the sector contributes 6% to the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

In Johannesburg, South Africa’s richest city and sub-Saharan Africa’s economic hub, the informal sector is considered an important part of the city’s economy, providing much-needed jobs and, most importantly, affordable goods for the poor.

But the city is in trouble. Lack of maintenance and neglect mean infrastructure is crumbling, resulting in little or no service delivery – a water crisis, a lack of housing, street lights that don’t function, and disintegrating roads.

Overall, the inner city is characterised by crime and grime, which is worsened by the lack of regulation of informal traders, who are found at every street corner selling their wares. At the same time, city officials with aspirations of living up to their mantra of “a world-class city” have resulted in the unintended consequences of trying to maintain a clean metropolis.

Without a proper and well-defined regulatory framework that includes demarcated trading zones, street vendors in Johannesburg’s CBD face constant, sometimes physical, abuse from city authorities through their law-enforcing municipal police, who conduct unannounced raids, confiscating wares and demanding huge fines if traders want their goods back. This also results in corruption, with street traders forced to pay a protection fee to keep their goods and escape persecution. The end result has been mistrust and a poor and antagonistic working relationship between city authorities and the informal sector.

In an interview with Africa in Fact, City of Johannesburg spokesperson Nthatisi Modingoane agreed that the informal sector significantly contributed to job creation and poverty alleviation.

Modingoane said the Metropolitan Trading Company (MTC), tasked with formalising the informal traders sector, was launched in 2000. “Through the MTC, the city has been able to provide trading spaces and the demarcation of designated trading areas at public transport hubs like bus and taxi stations and identify buildings where traders can operate like a market.”

But he admitted that progress had been slow because this was a difficult sector to manage. “The problem is that Johannesburg is a metropolitan city attracting many people from all over the continent. People see Johannesburg as a place where one can make it in life. That old mentality of seeing the city as ‘the City of Gold’ is still there in people’s minds. This puts enormous pressure on the city’s infrastructure and its services as the population increases fast.

“City authorities try, but it’s impossible to satisfy or service everyone – this includes the informal sector,” said Madingoane. He said the next phase would be to continue identifying land to provide more trading spaces, adding that as unemployment increases and many people turn to the informal sector, the problem of providing safe and humane trading spaces for street traders will always be a challenge.

Trading permits would be done through ward councillors, he added. Traders will first register at their ward councillor offices, and the registry compiled used to issue licences ward by ward. “This process, which looks workable, will start in earnest in May this year,” Modingoane said.

In the past, trading permits were issued haphazardly because there was no proper register. “The city has reviewed and approved its informal trading policy to focus more on a development and consultation approach with the informal trading sector through stakeholder engagement and fostering partnerships with all role players within the sector,” Modingoane told Africa in Fact. The city was also setting up informal trading committees to facilitate stakeholder engagements.

However, although the Johannesburg city authorities say they are working to regulate and improve the informal sector’s operating environment, the traders themselves tell a different story.

Thembi Maholo, 55, from Soweto, told Africa in Fact that street vending was the only job she’d known, starting at 13 when she would accompany her mother in Johannesburg’s inner city to sell fruit and vegetables. “It’s not easy being a street vendor,” the mother of four said, selecting fruit from a bucket in Lillian Ngoyi Street (formerly Bree Street). “We are at the mercy of the elements – rainy days, windy days or hot days we are here, and if that’s not enough, we face constant harassment from city officials who come unexpectedly in large trucks and load our goods away. It’s painful as you helplessly watch, but, as a single parent I have to come again so that I can feed my children,” says Maholo.

Sixty-year-old widow Xoliswa Mangcu from Meadowlands, who operates at a taxi rank in the CDB, said she wished she had a bit more money so she could order goods in bulk, which was cheaper.

“I have to pay more for buying in bits and pieces; it works out more expensive,” she said. “This is because our sector is not properly organised and regulated. If it was, we could buy in bulk as a cooperative or a group to get discounts and much better prices. Instead of being obsessed with harassing us, the city should assist us by forming co-operatives and registering us. We are willing, but they don’t do that. We want to be organised so that we can enjoy those benefits.”

Mandisa Ngqoko, 59, who also operates from the inner city, said her problem was securing cheaper and safe storage for her wares because she was forced to use public transport to get to the CBD and back home to Soweto at the end of each working day. “It’s cumbersome and tiring,” Ngqoko told Africa in Fact. “If I had enough money, I could hire or rent a storage place for my goods and not carry them home and back again the next morning. It’s tough, but we have to survive.”

More broadly, Rhodes University economics associate professor Mike Rogan has written that current interventions in support of the sector in South Africa were limited to micro-financing. However, this was a narrow view from a job creation perspective, focusing on a very small group of informal workers.

Writing in the Quarterly Labour Force Survey, a household-based survey that collects data on labour market activity, Rogan said: “What is needed is a strategy with a broader view of informal employment. It must focus on increasing the incomes and improving the conditions of workers in all segments of the informal economy”, adding that the sector had the potential to provide a point of entry into the labour market for many unemployed South Africans.

*John is not his real name

Max Matavire

Max Matavire is an award-winning journalist based in Port Elizabeth, South Africa. With over 15 years of experience, he has worked in South Africa's biggest media houses at a senior level.

He has also worked in Zimbabwe, and covered the entire Southern African region. His specialities are politics, local government, business/economics, health, and social development.