Water security is critical to building sustainable cities and ensuring progress towards other sustainable development goals, such as food security, good health and well-being, climate action, sustainable energy, quality education, and sustainable industrialisation and innovation.

The World Bank Group notes, quoting David Grey and Claudia Sadoff in their paper published in the journal, Water Policy (2007), that this goes beyond physical resource scarcity and entails “an acceptable quantity and quality of water for health, livelihoods, ecosystems, and production, coupled with an acceptable level of water-related risks to people, environments, and economies.” It further notes that “water insecurity slows growth and impedes development and human welfare” and “is typically driven by a combination of environmental, societal, technological, and governance factors.

“The most water insecure countries combine challenging hydrological environments with weak institutions and chronic underinvestment in water infrastructure… water security often intersects with other security issues, including energy security, food security, climate change, and national security.”

In Zimbabwe, water security is a top priority for the Bulawayo city council when it comes to service delivery. In Bulawayo, the country’s second-largest city, community boreholes, the provision of water through bowsers, water kiosks, and strict water rationing have, over the years, all been a regular feature of the city’s attempts to resolve the city’s longstanding water challenges and ensure ongoing water supplies.

In March 2024, when the city’s supply dams were critically low (29%), partly due to the El Nino-induced drought, the city council’s efforts to conserve the limited supplies saw the introduction of 120 hours of weekly water shedding. In late February this year, there was an improvement in inflows, with dams reaching 50%, leading the council to recommission some of its previously decommissioned dams. However, unless there are continued rains and inflows improve, water rationing continues as supplies remain insufficient.

The residents of Bulawayo have grappled – and continue to grapple – with erratic water supplies, and a sustainable solution is urgently needed. Meanwhile, the current major efforts focus on the Glassblock Bopoma dam as a short-term intervention and the Gwayi-Shangani dam as a permanent solution. First mooted in 1912 by the colonial government, the Gwayi-Shangani dam was finally begun in 2004 by the post-independence government. A Newsday report in October last year noted that the latest government figures indicated the dam was 60% complete. However, it is behind schedule as it missed several projected completion dates in 2019, 2022, 2023, and 2024 and is now expected to be completed in 2026.

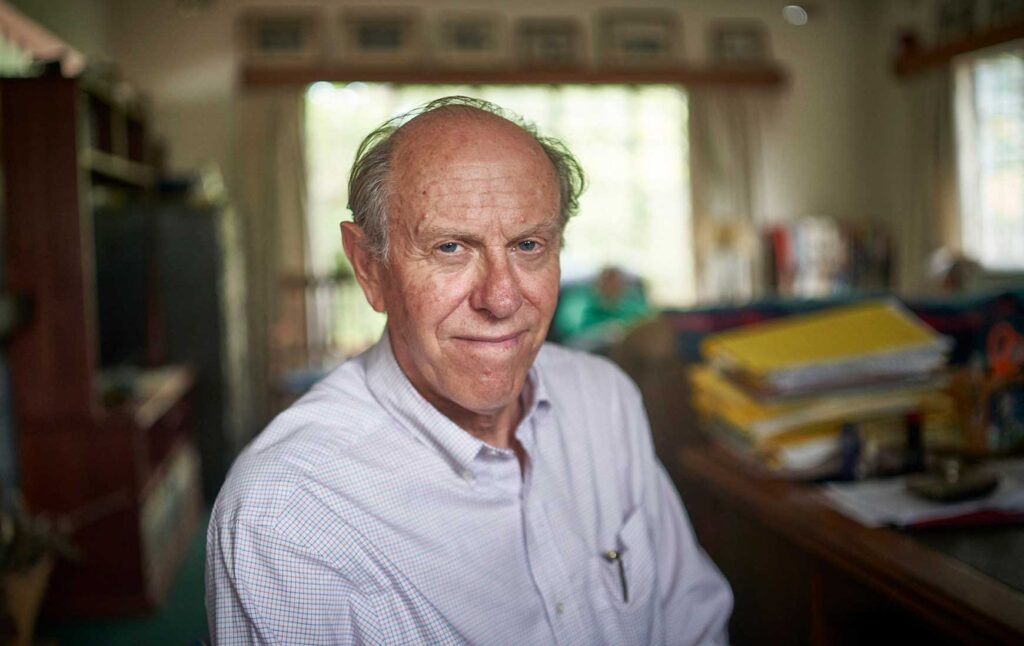

In an interview with Africa In Fact in March this year, Bulawayo’s mayor, Senator David Coltart, offered an in-depth insight into measures planned for ensuring the city’s water security.

The mayor began by noting that the previous council, in recognising Bulawayo’s population growth, the effects of climate change, and reduced inflows, had passed a resolution appealing to the government to declare the city a water shortage area. This, however, was not granted. Had it been, he said, the local authority could have unlocked much-needed third-party funding for building more dams and increasing the pipeline capacity of current water sources.

The senator said that in engagement with the city’s engineers when the city was running out of water last year, there had been a broad consensus that the immediate solution was to upgrade the Insiza to Ncema pipeline and the Mtshabezi to Insiza pipeline. This was expected to cost $1 million, which, in the context of government spending, was not a lot of money and would enable access to water in dams the council could not otherwise access quickly enough.

Coltart was also optimistic that the proposed Glassblock Bopoma Dam was a viable short- to medium-term intervention to the Gwayi-Shangani dam for improving the city’s raw water capacity. This new dam will be located in the Upper Umzingwane catchment area and will, once constructed, be the city’s second-largest water source after Insiza Dam. In January this year, the city council embarked on city-wide consultations with residents to elicit their opinions on whether the council could proceed with the raw water purchase agreement for this dam, whose Build, Own, Operate, and Transfer (BOOT) construction tender was awarded to JR Goddard Contracting in 2019. If successful, the Glassblock Bopoma Dam is expected to be completed by 2027 and is projected to guarantee the city’s future water supply until 2040.

However, Coltart emphasised that it was still crucial in the interim to expedite the completion of the Gwayi- Shangani Dam initiative by 2040. He added that “Gwayi-Shangani is going to cost $100 billion because the biggest engineering project is not so much the dam; it’s the construction of a 257 km pipeline, the pumps that they need, and critically, the extra power supplies, either thermal or a massive solar facility to power the pumps to get the water to the city. Gwayi-Shangani water will be four times the cost of water from the Glassblock Bopoma dam.”

Senator Coltart noted that, in light of the anticipated growth of African cities by 2050, the Gwayi-Shangani Dam was a sustainable alternative for Bulawayo’s long-term water security needs. Therefore, there was an urgent need to prepare for Bulawayo’s population, currently close to a million people, which was also likely to double in that time.

Coltart concluded the interview by noting that although ongoing rains had granted the city some reprieve, more rain was still needed in the coming months to get the city out of the woods.

Meanwhile, citizens hope that with an adequate water supply, Bulawayo, presently battling de-industrialisation, can begin to re-imagine its restoration as a potential investment, industrial, and tourism destination.

Sikhululekile Mashingaidze entered into the governance field while she was a part-time enumerator for Mass Public Opinion Institute’s diversity of research projects during her undergraduate years. She has worked with Habakkuk Trust, Centre for Conflict Resolution (CCR-Kenya), Mercy Corps Zimbabwe and Action Aid International Zimbabwe, respectively. This has, over the years, enriched her grassroots and national-level governance projects’ implementation and management experience. Her academic research interests are in the field of genocide studies, driven by her commitment to deepening her understanding of girls' and women’s experiences and their agency in reconstituting everyday life, and their inclusion in peace-building and transitional justice processes. Socially, she has a keen commitment to supporting girls' education, women’s economic empowerment and the fulfilment of their equitable and sustainable development in Africa’s underserved, often hard-to-reach communities. She enjoys writing and telling the stories of navigating everyday life.