Mozambique divided

The paths to prosperity are narrowing in this increasingly polarised country

On the surface, Mozambique’s capital Maputo looks like a poster child for a new, prosperous Africa. New buildings and construction projects have replaced the ravages of the 1977-1992 civil war. Along the central business district’s bustling Julius Nyerere Avenue, white-collar workers—civil servants, NGO workers, professionals—appear to represent the thriving new middle class that forms part of the Africa rising narrative.

This story and the statistics that bolster it offer only a partial picture of contemporary Mozambique. Growing social and economic fissures are starting to alienate even the privileged in this highly polarised country.

Growth in Mozambique has been high since the 1990s on the back of post-war reconstruction, aid and foreign investment. Recent offshore natural gas discoveries—one of which Forbesmagazine called the world’s biggest oil or gas find in 2013—seem set to increase this trend. A growth rate of 7% in 2013 is expected to expand to 8.5% in 2014, according to 2014 African Development Bank (ADB) estimates.

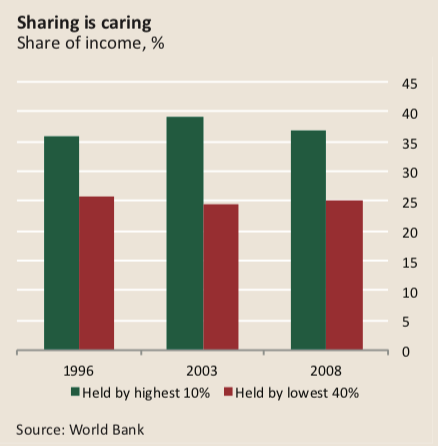

What these encouraging numbers mean in practice is more complicated. Many members of Maputo’s more affluent and educated perceive that wealth is becoming more concentrated.

“It is just five families that eat everything,” a university professor in her 30s said, reflecting a common sentiment that a small elite at the apex of Frelimo (Mozambique Liberation Front)—the party that has held power since Mozambique won independence from Portugal in 1975—is monopolising the benefits of the country’s new wealth.

This professor and others interviewed for this article asked to remain anonymous to spare any awkwardness that negative comments about the government—which in many cases employs them or their family—could bring.

“People are angry,” said one man in his mid-20s, who recently graduated from the nation’s prestigious Eduardo Mondlane University in the capital. He moved to Maputo from a provincial capital in the country’s south where his parents were low-ranking government officials. “Many of those I went to school with spent everything they and their families had to get an education, and after they graduated there is no work, and they have to go back to the provinces and live with their parents.” Before a university education and even low-level government connections would have given them a good chance to at least secure modest prosperity.

Even previous restricted modes of party-based social mobility are beginning to fray. The children of police officers, teachers, local government officials and those of similar backgrounds are no longer assured of moving up the income ladder.

“The future is uncertain,” said a former government minister. “There has been a huge increase in the number of universities but there is nowhere for the graduates to go. They are becoming increasingly frustrated and, unlike their elders, they are not attached to Frelimo in the same way. Even within Frelimo, the party machine is now just being mobilised for elections. We no longer listen to the base.”

If the privileged are beginning to feel alienated from the political system, the disaffection among the wider population is more dramatic. Despite high economic growth and reported declining poverty rates, urban unrest has escalated, as shown by the deadly riots in 2008 and 2010 after the prices of petrol, basic foodstuffs, water and energy skyrocketed, according to the Christian Michelsen Institute (CMI), an independent research group based in Norway.Though the economy is creating new jobs—such as temporary positions in construction or as domestic workers or security guards—they tend to be paid poorly, a CMI study showed.

The African middle class has drawn much attention since a 2011 ADB report classified nearly 350m people, or 34% of Africa’s population, as members of the middle class because they spend between $2 and $20 a day.

Such proclamations fit with the wider African rising narrative but the ADB’s definition of middle class is very far reaching. As anything below $2 a day is the World Bank’s definition of poverty, there is little between destitution and the middle class.

The problems with this definition are clearly evident in Mozambique, where 54% of the population lives below the $2 per day threshold, according to the latest World Bank development indicators.

While there are exceptions, the Mozambican middle class is traditionally defined by a combination of material assets and disposable income. They trace their origins to those who were relatively privileged during the colonial period. Membership in this group enlarged after independence with the so-called “emergentes” (“the emerging” in Portuguese)—those Frelimo loyalists who used state and party structures to advance their own social standing.

They earned a steady salary from white-collar jobs, usually as professional, mid-level civil servants, and after Frelimo abandoned socialism in 1989, as business people. In addition to material conditions, mastery of Portuguese, and increasingly English, reflected education and social background and afforded membership the middle class.

But even for those with a degree of wealth and standing, there is concern that spiralling prices, unmet expectations and growing social polarisation will bring the system crashing down. “I think there could be another civil war or a general revolt,” said a well-educated researcher in her early 30s who works for a major consulting company and lives in an affluent area. “I will be caught in the crossfire. I am not part of the top, but I doubt too many people will make fine distinctions if trouble comes.”

The ADB’s triumphal narrative ignores the polarisation and politics that come with economic growth. Traditional indicators of middle class life—stability, prosperity and upward social mobility—are very difficult to come by in contemporary Mozambique; far more difficult than simply spending up to $20 a day.