The German word, zeitgeist, aptly describes the emergence of the BRICS grouping of nations. Zeitgeist encapsulates the spirit or mood of a particular period of history, rooted in the ideas and beliefs of the time.

BRICS is an acronym for the grouping of the world’s leading emerging economies, namely Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa. The genesis of BRICS is in the banking crisis of 2007–08, when the G20 asked countries such as China, India and Indonesia to provide liquidity to the Global North’s collapsing banking system.

The Global North’s banking crisis created an opportunity to rethink the global financial system.

For decades, the Global South has been concerned about the unfair trade practices of the North. These practices include the imposition of credit conditions that, in many cases, do little to ease the financial burden of so-called developing countries. Indeed, the conditions attached to loans secured from institutions in the Global North often leave the indebted country worse off than it was prior to the execution of the loan agreement.

The formalisation of what the 1991 South Commission report dubbed “the locomotives of the South” created an opportunity to challenge the Global North’s financial hegemony.

After all, it was now clear that economic development in the Global South had not been helped by the Breton Woods institutions, whose governance is tightly controlled by Europe and the United States.

It’s this reality that has made BRICS an attractive alternative in the eyes of many Southern nations.

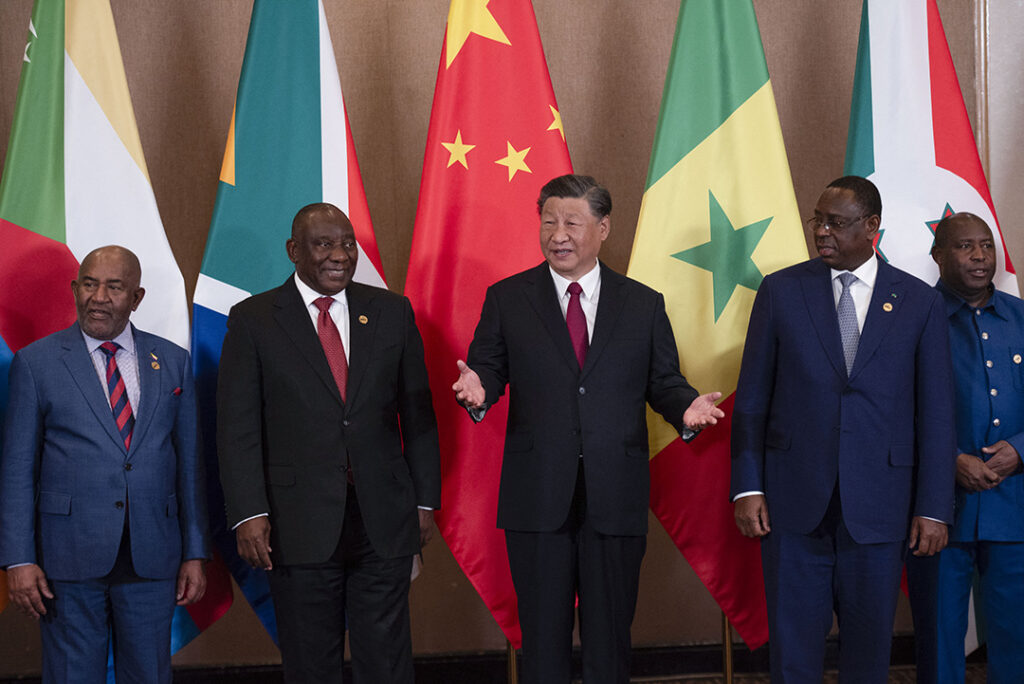

As was clear at the 15th BRICS Summit recently held in Johannesburg, South Africa from 22-24 August 2023, countries impatient with the current international financial system are looking to BRICS for fairer and more respectful financial agreements with real potential for economic growth.

The Summit, in a sense, brought back memories of the core purpose of the 1970s clarion call by the Group of 77 and non-aligned countries (plus China) to establish a New International Economic Order.

The highlight of the 15th BRICS summit was its transformation from BRICS to BRICS+, with the admission of Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. The six countries will officially join the group in January 2024.

The new members will add their voices to the call for a more equitable global governance system, including reforming the UN Security Council with a view to making it more globally relevant and accountable.

A wind of change is blowing as nations representing the majority of the world’s population endeavour to create an economic system that respects their sovereignty and maximises opportunities for equitable global prosperity.

If British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan were alive today, he would probably have recognised another “Wind of Change” and talked about BRICS as a political and economic reality we had to live with, whether we liked it or not.

This wind of change is evident in a report released on July 20, 2023, by the United Nations titled “A New Agenda for Peace”, in which the UN Secretary-General, António Guterres, says: “We are now at an inflection point. The post-Cold War period is over. A transition is underway to a new global order. While its contours remain to be defined, leaders around the world have referred to multipolarity as one of its defining traits.”

The wind of change is blowing the world away from the post-Cold War era, where the United States and its close allies, Europe and Japan, exerted their unipolar power over the rest of the world, to a “multipolarity” era.

The UN report rightly perceives the ending of the unipolar world and the emergence of a multipolar world.

While the neo-colonial structure of the world system remains largely intact, the rise of BRICS is offering alternative options to the established order. This is its appeal.

In 2015, the New Development Bank (NDB) or BRICS Development Bank, as it was then, was founded and headquartered in Shanghai, China, to give the BRICS nations more control over development financing and an alternative to the World Bank and International Monetary Fund.

BRICS nations have also been building a “BRICS Pay” a payment system for transactions among the BRICS nations without having to convert local currency into dollars.

The de-dollarisation initiative of the BRICS nations is not aimed at replacing the dollar but rather at offering alternatives to facilitate bilateral trade in local currencies. This is currency democracy.

The benefit to nations wishing to join BRICS is its complementarity when deciding on development financing and the role of the IMF.

BRICS does not pose a danger to the global power becoming more fragmented and widely dispersed; on the contrary, it’s the West refusing to come to terms with the wind of change and adapting to the new reality by taking into account the new developments and interests of all nations.

The genesis of the wind of change springs from the spirit of the United Nations Charter, for which BRICS is a catalyst.

BRICS is committed to a world of peace and stability and supports the central role of the United Nations, its purposes and principles, as enshrined in the UN Charter, and respect for an equitable application of international law.

The zeitgeist in relation to the United Nations is reform.

Prime Minister Mia Amor Mottley of Barbados’ voice of wisdom makes a case for the reform of the United Nations as well the Bretton Woods Institutions, viz the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund.

In 2022, at the Caribbean Nations Security Conference, she advocated the need for transparency and sincerity in today’s world, saying:

“Territorial integrity must mean territorial integrity for all. Non-incursion must also mean non-incursion for all. Non-interference must also mean non-interference for all. And it is to those high and lofty goals established in the United Nations charter that we must continue to work for.”

She then questioned whether the UN, formed 78 years ago, can continue to function the same way it has given the fact that at its formation only 50 countries participated.

The majority of the subsequent member states did not even exist when the United Nations was formed. Accordingly, the role of the permanent five in the Security Council raises fundamental questions of whether we could have “first-class and second-class nations.”

A Security Council with the power of veto in the hands of five nations is unacceptable, and therefore the reform has to be not only in its composition but also in the removal of the veto.

So commitments to international policy and stability must be reviewed to be inclusive of all nations.

The reform of the United Nations as well as the Bretton Woods institutions is critical to going forward with credibility and stability in our world. The spirit of fairness and togetherness is needed to bring about peace, love and prosperity in the world. This is the hard reality on which decisions must be made rooted in equity.

Such was the hard reality of the decisions that framed the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948.

On 18 July 2023, I attended the meeting of the BRICS and Africa: Partnership for Mutually Accelerated Growth, Sustainable Development and Inclusive Multilateralism held in Boksburg, South Africa.

It was telling that this meeting and the fifteenth summit in August took place on the 75th year anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

The importance of the anniversary must not be lost on us. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights was adopted by the UN General Assembly on 10 December 1948, as a consequence of the horrors of the Second World War.

The document, elegantly crafted, movingly inspirational and visionary, honours and protects the sanctity and rights of all peoples.

The drafters, representing various political, cultural and religious backgrounds, reverently animated the document with a rich global diversity and profundity.

Women from various countries played a key role in crafting the Declaration by ensuring women’s rights were included.

One such delegate was Hansa Mehta of India, credited with changing the phrase “All men are born free and equal” to “All human beings are born free and equal” in Article 1.

The drafting committee was chaired by Mrs Eleanor Roosevelt, widow of American President Franklin Roosevelt.

On December 10, 1948, the General Assembly, meeting in Paris, adopted resolution 217 A (III) famously known as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

A Chilean member of the drafting sub-committee, Hernán Santa Cruz, described it as a “truly significant historic event in which a consensus had been reached as to the supreme value of the human person, a value that did not originate in the decision of a worldly power but rather in the fact of existing—which gave rise to the inalienable right to live free from want and oppression and to fully develop one’s personality.”

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights is sacrosanct, embodying what is taught in all faiths, viz., the supreme value of the human being.

The document has inspired the adoption of over seventy human rights treaties, applied today on a permanent basis at global and regional levels, with references to it in their preamble.

The 75th anniversary of the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights invites us to pause and reflect on the world as it was 75 years ago. It invites us to contemplate and appreciate deeply what inspired the drafters to produce a magnificent document of genius and wisdom.

75 years ago, the world was divided between the Eastern and Western blocs. It was an era of the Cold War, and in this Cold War, the warm Universal Declaration of Human Rights was crafted.

How was this possible? The drafters simply focused on what matters and unifies—that is, people matter. This is the inalienable gift of humanity that the drafters recognised, and we must not forget that people matter.

They saw a person, irrespective of religion, colour, creed, gender, tribe, nationality, or political ideology, as endowed with an inalienable gift of humanity made in the divine image.

Concisely summed up The Universal Declaration of Human Rights obligates us to:

“Do unto others as you would have them do unto you”. ( Matthew 7:12).

This is the bulwark against people’s inhumanity towards others, imperialism, greed, arrogance, neo-colonialism, hatred, exploitation, and all evil beliefs and ideologies that seek to demean people and polarise our world.

Serendipitously, President Nelson Mandela’s birthday (July 18) was at the opening of the BRICS Political Parties Plus Dialogue. This great statesman’s life exemplified the spirit of The Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

His life was dedicated to fighting all forms of white or black domination and nurturing democracy, peace, human rights, and social justice.

President Mandela placed human solidarity and concern for others at the centre of the values by which he lived. This, for him, defined a meaningful life.

In our world of division, conflict and violence, he sought to build bridges of love, friendship, solidarity, and hope.

It’s the spirit of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights that President Mandela lived.

75 years ago, a divided world traumatised by the horrors of World War II, grappled to steer a course towards values that unite people and nations. It inched towards a holistic world but fell short.

75 years later, our divided world needs to remember and reboot to steer the same course and not fall short of a holistic world.

Our world faces a plethora of challenges that transcend national boundaries, such as climate change, terrorism, global pandemics, economic interdependencies, and migration crises.

These challenges need collective action and global solutions. The answer is in multilateralism or multipolarity as a solid foundation for nations coming together, sharing their expertise, and jointly addressing these issues.

Only multilateralism can promote peace and stability by fostering dialogue, encouraging nations to engage in peaceful negotiations to resolve conflicts through peaceful means, and finding common ground for mutual benefit.

We need to rediscover the values enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. These values point us to the importance of the well-being of people and nations as the essence of life. It’s an awareness we need to nurture in global politics.

In 2019, the former First Minister of Scotland, Nicola Sturgeon, delivered a TED Talk explaining the far-reaching implications of a “well-being economy” which embraces factors like equal pay, childcare, and mental health.

For ages, the measure of a country’s success has been through Gross Domestic Product (GDP). However, this has limitations as a measurement, so a much broader definition is needed of what it means to be successful as a country.

So in 2018, Scotland took the initiative to establish a new network called the Wellbeing Economy Governments group comprising as founding members the countries of Iceland and New Zealand; with the unforgettable acronym of “SIN”- Scotland, Iceland, and New Zealand.

SIN focuses on the common good and broadening the definition of GDP in that the objective of economic policy should be collective well-being: how happy and healthy a population is, not just how wealthy a population is.

Sturgeon argues that the focus on well-being stirs up what really matters in our lives, what we value in the communities we live in, what kind of country, what kind of society, and what kind of world we really want to be.

This is the zeitgeist of our time, which in a broad context frames the BRICS nations in an alternative pursuit of the well-being of the peoples of the world.

The BRICS objectives are non-interference, equality, and mutual benefit, and its pillars of political and security, economic and financial, cultural and people-to-people exchanges do not pose a threat to world peace and stability.

BRICS offers us a better chance of creating a more equitable, wholesome world than exists now. A world where equal importance is given to levelling inequality as to economic competitiveness.

The zeitgeist of our time is drawing us from a world of greed to one of generosity, where we can nurture the spirit of fairness and togetherness, bringing about peace, love and prosperity in the world.

BRICS is the vision of a future characterised by a transformed system of global governance and a multipolar world that will contribute to the peace and security of all nations, sustainable development and goodwill among nations and peoples of the world.

Let’s seize the moment with wisdom.

The Rt. Rev. Dr. Musonda Trevor Selwyn Mwamba is President of the United National Independence Party (UNIP) Zambia and former Bishop of Botswana

Musonda Trevor Selwyn Mwanda

The Rt. Rev. Dr. Musonda Trevor Selwyn Mwamba is President of the United National Independence Party (UNIP) Zambia and former Bishop of Botswana.