Corruption is commonly understood as an abuse of political power for private gain. This, however, falls short of capturing the evolution of the nature of corruption. Considering recent developments, corruption is believed to involve not only the abuse of public office but also the abuse of power and influence vested in a person because of holding a political office, holding an influential role in a corporation, having personal wealth or access to significant resources, or having elevated social standing. As a result, corruption does not only lead to personal gain but can also involve gains for a collective entity such as a political party, a corporation, or a group of people.

Corrupt practices have garnered much attention in recent decades. There are several factors in this, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Particularly after the end of the Cold War, the globalisation phenomena that brought frequent contact with various actors from different countries, the greater reliance on the market for economic decisions that pursue efficiency, the increase in the number of countries with democratic governments, as well as the increasing role of Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) and the media in publicising the problem, explain the increasing attention the problem is attracting.

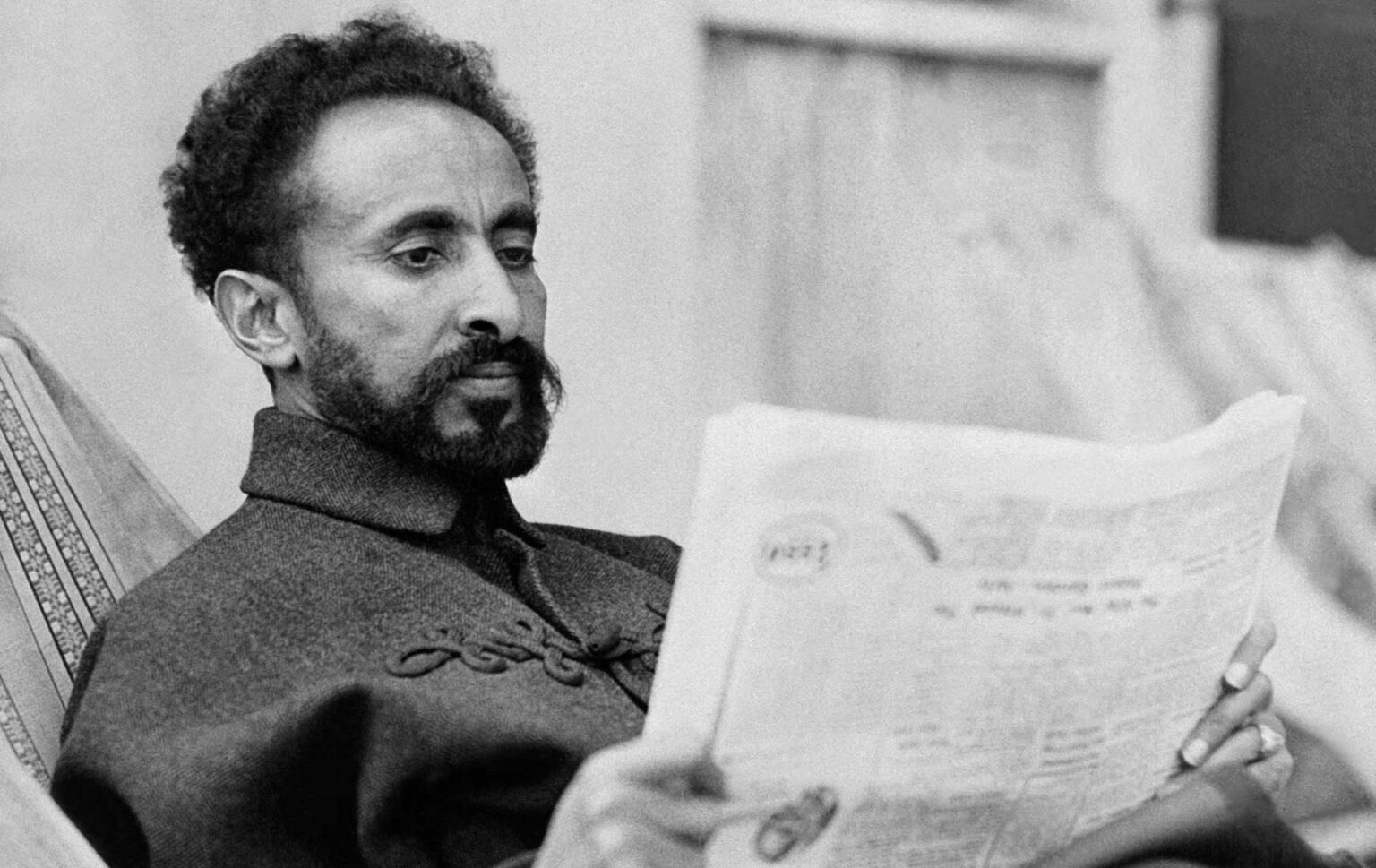

Corruption in Ethiopia, mostly in its petty form, is perceived to be rooted in the country’s traditions. In particular, giving gifts to public officials to win their favour and influence decisions has been a long-established traditional practice. Grand corruption, in the form of the embezzlement of public funds and the misuse of power for personal gain, began to creep in during the reign of Emperor Haile-Selassie (1930-1974) and worsened during the period of the Derg (a junta that deposed the emperor and ruled the country until 1991). However, it was not as prevalent as it is now.

A disturbing trend in the pervasiveness of corruption has been seen in the past three decades (Zemelak Ayitenew Ayele (2017), Corruption in Ethiopia: A Merely Technical Problem or a Major Constitutional Crisis?). The rise and expansion of party-owned businesses and their presumed affiliates are believed to have aggravated the situation in recent times. In the past three decades, various governmental and NGO reports have revealed that top officials of the regime were involved in grand corruption schemes that led to multiple instances of political instability and crackdowns.

Some of the factors that explain the prevalence and pervasiveness of corruption in Ethiopia include the absence of transparency and accountability in running public affairs, the inefficiency of the legal system, violations of the rule of law, weak civil society participation in the fight against corruption, and the absence of an effective anti-corruption agency that coordinates anti-corruption activities. As the problem reached an alarming stage, the government was forced to establish an “independent” watchdog to address it.

This article focuses on the ineffectiveness of the country’s anti-corruption watchdog. The Federal Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission (FEACC) was established in 2001. Officially, it was a result of the civil service reform initiative, the findings of which, among other things, recommended the formation of such an institution. However, the context of its establishment was politically charged. It was under the circumstances of the split within the ruling EPRDF that the commission was established. There was, therefore, a widespread belief that the institution was a political tool. This view was reinforced by the immediate arrest of the leader of the dissenters in the ruling party.

Be that as it may, the commission was established with a multi-purpose model of prosecutorial and law enforcement powers. Although it did not have a constitutional basis, the parliamentary act that led to its establishment laid down broader powers and functions for the commission. Besides educating the public about corruption, the act gave the commission the powers of prevention, investigation, prosecution, and asset recovery.

However, it was made to operate at the federal level and in the two federal cities, namely Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa, since regional governments have the power to form similar institutions. The commission was also made accountable to the Prime Minister, and its head was appointed by parliament on nomination by the Prime Minister. The term of appointment of the Commissioner or the Deputy Commissioner was appointed for a term of six years.

In 2005, parliament proclaimed an amendment bill (proclamation No. 433/2005) to provide the commission with more power to combat grand corruption. Accordingly, the investigation and prosecution powers of the police and the public prosecutor specified under the criminal procedure code and other associated laws were transferred to the commission.

Nonetheless, a further amendment bill was issued in 2015 that narrowed the mandate of the commission and deprived it of almost all the power given to it in the 2001 law and the 2005 amendment bill. The commission’s investigative and prosecutorial mandates have been transferred to the Attorney General, and the commission is, therefore, left only with its corruption prevention mandates, which include preparing and ensuring the enforcement of codes of ethics in public offices and enterprises. It is also authorised to study and identify methods and procedures of decision-making in public offices to assist the latter with introducing corruption-proof working methods.

Moreover, it is responsible for creating awareness about corruption and its adverse consequences for the country’s economic development. It also has the authority to register the assets and financial interests of public officials who are legally required to have their assets and interests registered by the commission. More importantly, the amendment bill made the commission accountable to the prime minister and its budget is determined by the council of ministers.

The most recent amendment in 2021 also brought new changes. Whereas its mandate had been restricted to public sector entities, the commission’s jurisdiction was extended to include private companies for the first time. However, political parties and religious organisations still do not fall within the purview of the commission. Furthermore, the commission is still accountable to the prime minister’s office.

In just four years, the FEACC has reportedly witnessed three changes in leadership. It appears that the FEACC remains subject to a high degree of political influence. At present, any complaints or tip-offs the commission receives are supposed to be passed to the Attorney General’s office for investigation and prosecution. Some reports suggest that the FEACC is petitioning Parliament to have its investigative and prosecutorial mandates returned. However, currently, the commission’s remit is limited to leading national preventive measures against corruption.

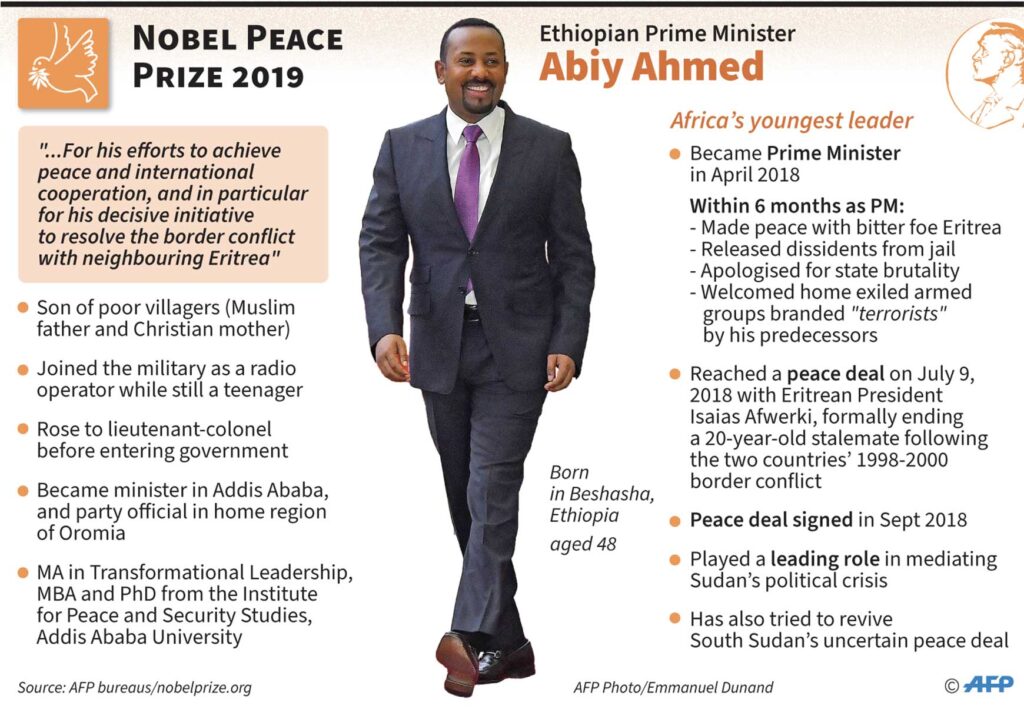

In what appears to be a new move to deal with the problem, in November 2022, the Ethiopian government declared the establishment of a national committee to coordinate the government’s campaigns against corruption. Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed announced that corruption posed a threat to the country’s socioeconomic development. The new seven-member committee includes the Ethiopian minister of justice, the director-general of the National Intelligence and Security Service (NISS), and the FEACC commissioner. However, the mandate of this National Anti-Corruption Committee vis-à-vis existing anti-corruption institutions remains unclear.

One month into its establishment, the committee was reported to have frozen the assets of suspect bank accounts in addition to freezing the transfer of properties in some regions. The committee reportedly started by focusing on sectors such as land and public housing management, security and the justice sector, financial sector, government revenue and customs system, as well as service delivery, administration, and government procurement sectors.

The committee stated that numerous senior officials, including the director-general of the Financial Security Service Directorate, alongside others from law enforcement agencies, judges and prosecutors, had been arrested. It was also reported that regional governments were expected to establish their own anti-corruption committees to conduct evaluations of regional officials.

It remains to be seen how this latest anti-corruption purge by the federal government plays out against the backdrop of the country’s fragile peace and complex political division. It is potentially sensitive given previous administrations’ record of using anti-corruption crackdowns as an instrument to curb the influence of political factions and regional authorities perceived to be disloyal to the central government. Since its initial measures, the committee has remained inactive.

In summary, the FEACC, from the outset, was established to quell dissenting voices that emerged within the ruling EPRDF party, and the bill establishing it was first amended under political turmoil in the run-up to the eventful 2005 elections. Subsequently, the bill has been amended twice: first, under the cloud of brewing political opposition and uncertainty after the death of the country’s longtime strongman leader, and second, following the 2018 political changes. These cyclical amendments appear to be driven by political motives rather than a genuine drive to fulfil the public interest.

The net effect of all these, despite the amendments, is that the FEACC remains within the firm grip of the executive as it is accountable to the prime minister and its budget is determined by the council of ministers. The Prime Minister appoints the commissioner, of course, subject to approval by the parliament. In an ironic twist of events, the FEACC was only made a member of the National Anti-Corruption Committee within the past year. This is a testimony to the reduction of its function in both law and practice to an anti-corruption educational outfit focusing on educating the public. The result is an institutional watchdog falling asleep and, therefore, being ineffective in guarding resources in public coffers.

The FEACC must, however, claim its rightful place as a watchdog in the real sense. This requires some improvements in both laws and practice. First, the commission must reclaim its investigation, prosecution, and asset recovery functions. Second, it must be guarded from the dictates and control of the executive. Third, its institutional accountability must fall to parliament. Fourth, its budget and other requirements must be approved by parliament. Fifth, it must have well-sanctioned collaborative schemes with CSOs and the media.