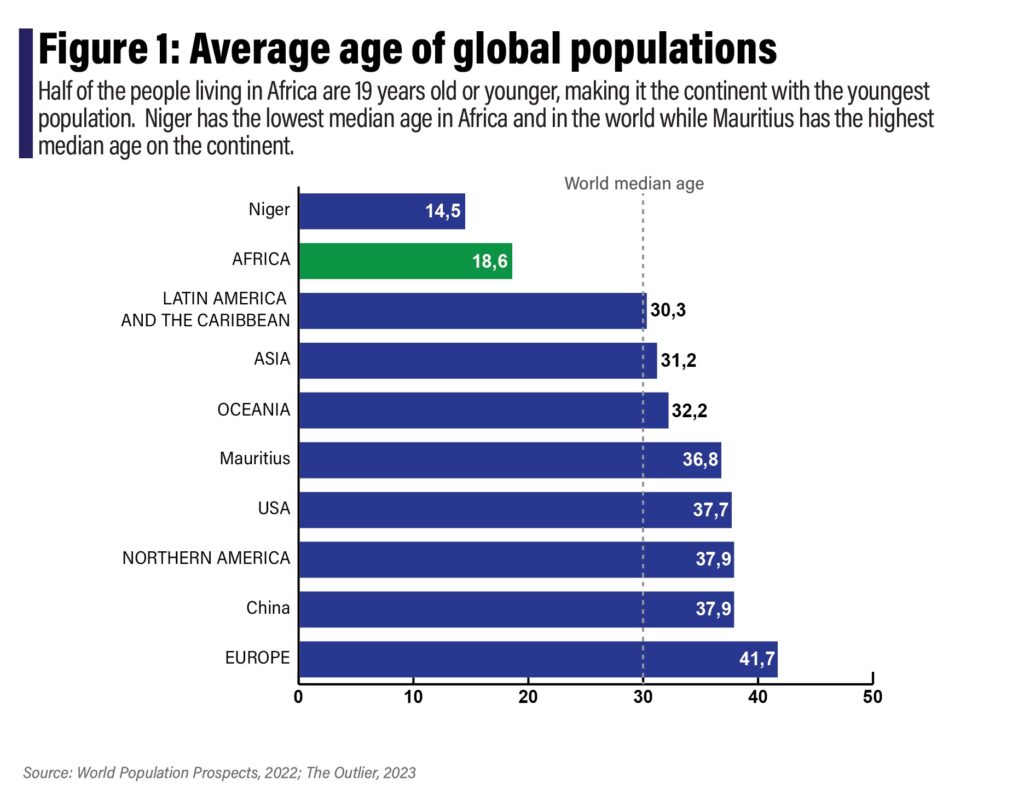

Africa today has one of the world’s fastest-growing populations and boasts some of the youngest working-age populations. It is projected that by 2040, Africa’s urban population will increase by more than half a billion people and that the continent’s population will surpass both those of China and India – the world’s largest labour economies (Figure 1).

Alongside this accelerated growth in urban populations, however, comes a heightened energy demand to improve livelihoods and efficiency, and facilitate industrial production and mobility in these economies.

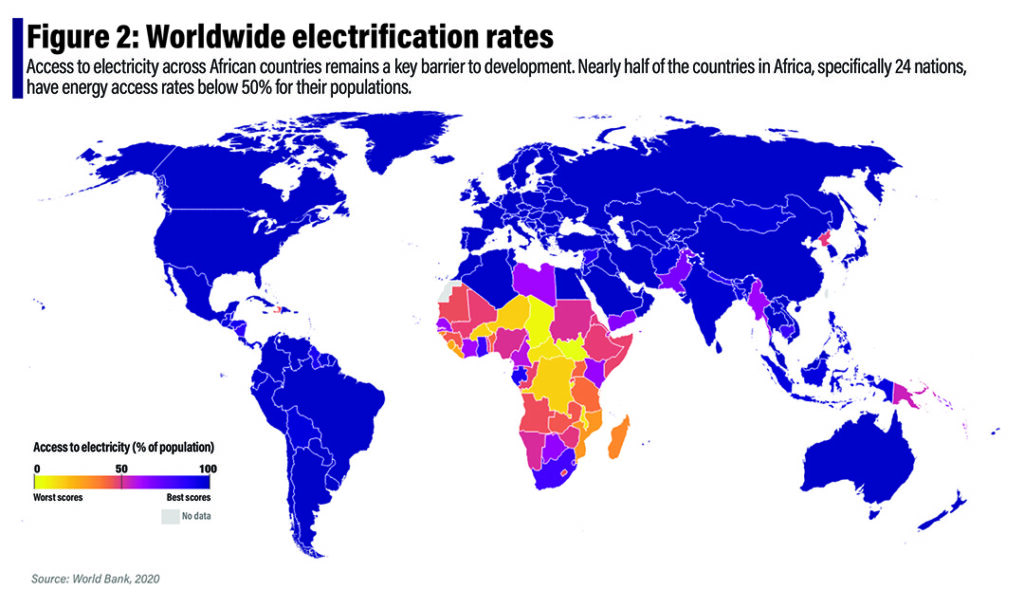

Compared to global electrification rates, energy accessibility across the continent continues to hamper socioeconomic development and remains a significant barrier to its development potential (Figure 2).

Between 2015 and 2019, the number of people who were gaining access to electricity was improving by around 9% each year. But in 2019, and for the first time since 2013, this number stagnated and the sub-Saharan share of the global population without access to electricity rose to 77%. This means that more than three-quarters of the world’s people without access to electricity live in sub-Saharan Africa.

According to the World Bank, 48%, or roughly 600 million people in Africa did not have access to electricity in 2020. Additionally, the overlapping crisis of the Covid-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 reversed positive trends and exacerbated energy access globally, leading to 4% more people living without electricity in 2021 than in 2019.

Within the continent, regional disparities can be observed. In North Africa (Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, and Morocco) electrification rates are upwards of 99%, while the largest populations without access to electricity live in the DRC, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Tanzania, Uganda, and South Sudan (IEA Africa Energy Outlook report 2022; Tracking SDG7 Report, 2022).

Elsewhere, countries such as Ghana, Kenya, and Rwanda are on track for full access by 2030, while South Africa has continued to grapple with declining energy availability as a result of rolling blackouts, or load-shedding (IEA Africa Energy Outlook report 2022; CSIR Energy, 2022).

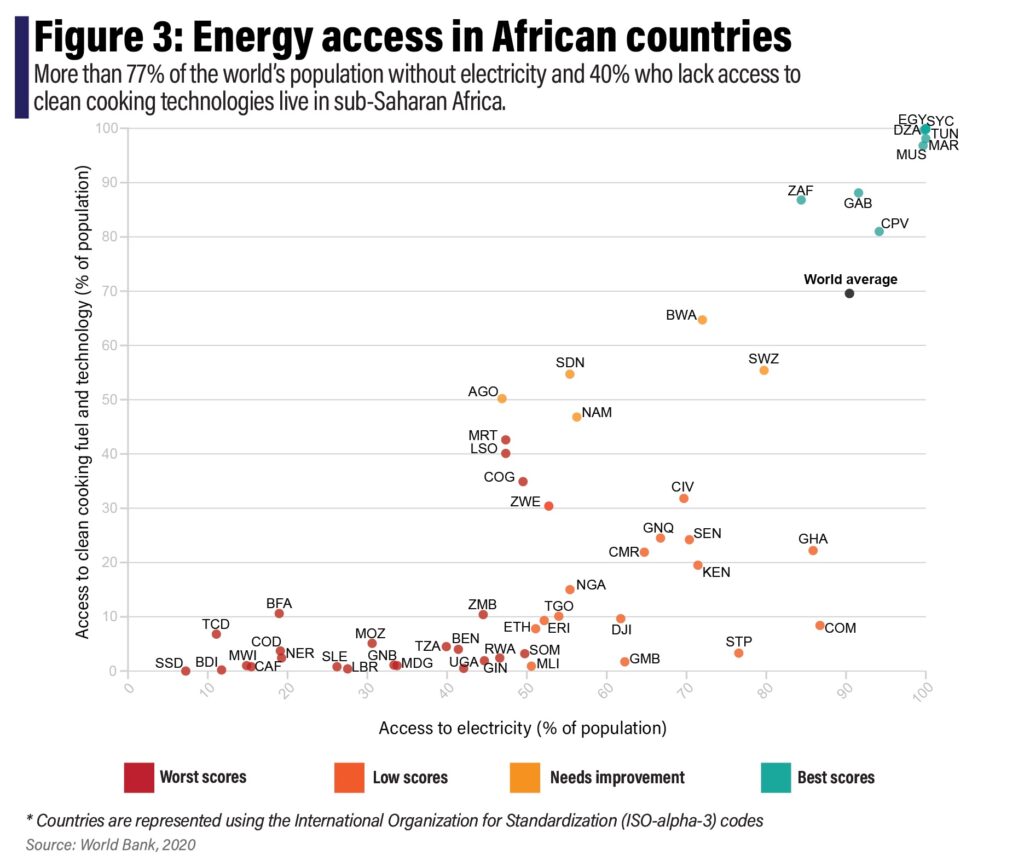

Even more concerning has been the sluggish progress in access to clean cooking fuels and technologies. These are alternative energy sources and cooking methods that are considered less harmful to air quality, have a less environmental impact and, most importantly, do not have the health risks associated with traditional cooking methods that rely on solid fuels such as wood or charcoal. In sub-Saharan Africa, access to these technologies remains poor, with the number of people having no access to clean cooking set to rise to more than 1.1 billion by 2030 from 970 million in 2020.

According to the IEA, the improvement rates to address this deficit and reach the universal access target as set by SDG 7 require an unprecedented reversal of current trends. However, if this target is achieved, it will bring with it a reduction in premature deaths by about 500,000 a year, drastic reductions in the time spent gathering fuel and cooking, and alleviate the burden of unpaid household work for millions of women, allowing them to pursue education, employment, and civic involvement.

As mentioned earlier in this article, more than 77% of the world’s population without electricity and 40% who lack access to clean cooking technologies live in sub-Saharan Africa and this number is accelerating (Figure 3).

Delayed progress is largely attributed to rapid population growth rates and the associated increase in energy demand.

Energy demand in Africa grew steadily at 2.4% annually between 2010 and 2019. Meanwhile, the uptake of access to electricity has lagged at 2.3% and the uptake of access to clean technologies has risen at only 2% annually measured over the same period. Simply put, this means more people are being born than are being provided for.

At the UN High-level Dialogue on Energy in September 2021, it was reported that achieving energy access targets in developing economies would require roughly $40 billion annually; $35 billion in annual investment flows for increasing access to electricity and $6 billion for improving access to clean cooking technologies.

In 2020, however, international financial flows to developing countries decreased by more than 20%, which is part of a persistent downward trend of diminishing investment that started even before the pandemic. In context, investment flows peaked in 2017 and accounted for $24.7 billion, almost double what was disbursed in 2019 ($10.9 billion).

Another concern is that investment in clean energy is spread unevenly across the continent with only 10 countries accounting for 90% of private international investment in the past decade, and with South Africa receiving the lion’s share (40%), according to the IEA.

Historically, fossil fuel investment has made up the bulk of energy investment, but this has since shifted as the global focus on climate commitments has increased, which offers great promise. Several African countries have announced important pledges. At COP26 in Glasgow in 2021, Morocco pledged to cease the development of any new coal-fired power stations, while Egypt pledged to phase out its existing power stations.

South Africa has announced commitments to decarbonise its economy as part of the Just Energy Transition Partnership. Critically, 12 African countries have pledged to reach carbon neutrality by between 2050 and 2070: namely Cabo Verde, Côte d’Ivoire, Liberia, Malawi, Mauritania, Mauritius, Namibia, Nigeria, Rwanda, São Tomé and Príncipe, Seychelles, and South Africa as of 2020.

However, following the return of several European countries to coal amidst soaring gas prices due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the “back-sliding” on climate commitments by the world’s largest contributors has elicited apprehension from several African leaders. At COP27 in Egypt last year, African delegates called out the hypocrisy, arguing that their countries should be allowed to develop fossil fuel resources if they help alleviate poverty.

At the same time at COP27, the African Union adopted the Common Position on Energy Access and Just Energy Transition, which stated that “Africa will continue to deploy all forms of its abundant energy resources including renewable and non-renewable energy to address energy demand”.

Ultimately, though, progress toward the SDG 7 target of ensuring access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy remains slow in Africa. Increasing population growth rates threaten to widen this gap and further entrench energy poverty, pushing millions of Africans into extreme poverty.

And while it is true that African nations should be allowed to pursue the development of energy infrastructure independently; progress in the past decade has suggested that its current development path has been unfruitful.

Even if diverse energy infrastructures are the most likely and preferred outcome, commitments to energy development still demand far more dedication and targeted focus. It is paramount that African leaders seriously consider what the sustainability and impact of its energy infrastructure will look like in the next few decades and how the energy needs of its young, fast-growing and rapidly urbanising population and economies are being met in that scenario.

Mischka Moosa is a data journalist at GGA. She holds a Bachelor of Social Science with majors in Gender Studies and Political Science that she obtained from the University of Cape Town. Her focus of interest is on decolonial approaches to justice, development and transformation in Africa.