In the absence of alternatives, most jobs are informal

Widespread recognition that the informal economy is expanding rather than declining across the developing world has drawn growing attention to measuring its size. Owing to myriad measurement problems and divergences in definitions and methodologies, efforts to measure the size of national informal economies and to derive regional averages should be treated as orders of magnitude rather than as hard numbers.

Despite their limitations, these measurement efforts are valuable because they highlight the contemporary significance of informality, and have played a key role in putting the informal economy back on the development agenda after a period of relative neglect during the 1990s, when many felt that liberalisation had made the informal economy obsolete. In the case of sub-Saharan Africa, recent efforts to measure and compare the size of informal economies have had a particularly dramatic effect on development policy debates.

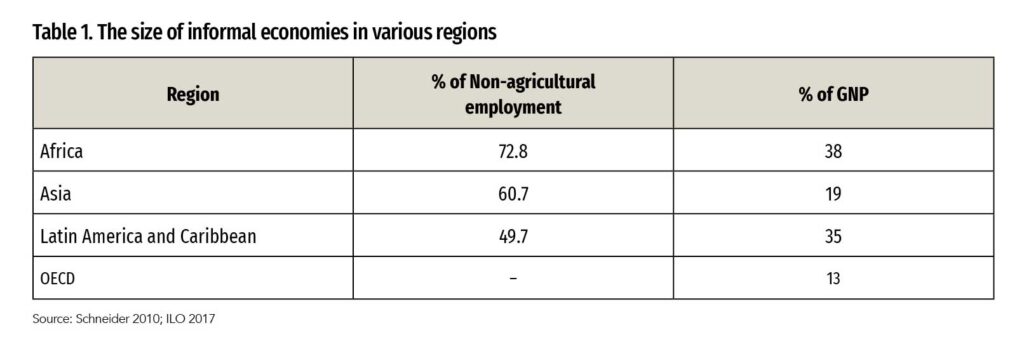

Table 1 presents 2017 statistics from the International Labour Organization (ILO) and the World Bank, showing that, across the developing world, the informal economy now accounts for over half of the non-agricultural labour force, and for over one third of gross national product (GNP). In Africa, these figures rise to nearly three quarters of the non-agricultural labour force, and nearly 40% of GNP.

In addition to being larger than the formal economy in terms of employment, Africa’s informal economy is growing rather than shrinking in the face of economic growth. Some 80-90% of new jobs are created in the informal economy, while the formal economy has been contracting in most African countries. Far from being replaced by the formal economy over time, the African informal economy is rapidly becoming the “real economy”.

The huge size of Africa’s informal economy suggests that we need to look at its internal dynamics to understand its growth. However chaotic the continent’s economy may seem, such a large informal economy could not operate at all without some form of internal organisation. An informal economy that caters for such a vast share of African populations must develop networks and institutionalised patterns of organisation to prevent society from grinding to a halt.

The fact that African informal economies are so large relative to the formal economy also raises questions about where the real regulatory power lies on the continent. When the informal economy becomes larger than the formal economy, does it become the dominant regulatory force in the economy? Does the size of the informal economy alter the relationship between the informal economy and the state? Does it make informal regulation the norm, and formality the aberration?

Understanding African informality requires an awareness of how the size and organisation of informal economies on the continent have been shaped by historical factors. A closer look at these economies reveals important differences between different parts of the continent with regard to the size, composition and complexity of the informal economy. These differences have been shaped not only by contemporary variations in the regulatory context, but also by distinctive historical experiences during the pre-colonial, colonial and post-independence periods.

A key influence of the pre-colonial period relates to the presence of centralised states or large-scale religious systems, both of which served as frameworks for the organisation of long-distance trading networks and indigenous commercial institutions capable of operating across communal and ethnic boundaries.

Economic historians have detailed the existence of well-developed centralised states in West Africa, including the Asante and Hausa states, and to a more limited extent in East Africa, in the centuries before colonialism. These states provided both the resources and institutional support for the development of markets, commercial institutions and long-distance trading networks.

Large-scale religious systems, including Islam and a range of indigenous oracular religions also played a central role in the development of indigenous economic networks and large-scale commercial institutions in pre-colonial West as well as East Africa. In stateless societies such as the Igbo of West Africa, and the Somali of East Africa, oracular religions were key to the emergence of regional trading systems in the former, while Islam underpinned the development of long-distance trading networks in the latter.

Colonialism created a new layer of influences on the development of informal economic organisation. The impact of colonialism reinforced the greater scale and complexity of informal economic networks in West Africa, while suppressing such development in much of central, East and southern Africa.

The economist Thandika Mkandawire argues that West Africa’s cash crop economies – Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Tanzania, Togo and Uganda – tended to be more permissive of indigenous economic activity. Meanwhile, the labour reserve economies of southern Africa and parts of East Africa, and to a lesser extent, the concession economies of central Africa took extensive measures to suppress indigenous economic activity that might compete with wage labour.

According to Mkandawire, in colonial labour reserve economies – including Angola, Kenya, South Africa, Namibia, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Botswana, Lesotho, Swaziland and Mozambique – measures were taken to block alternative sources of income that might compete with the wage economy. These measures included disruption of peasant agriculture, job discrimination, criminalisation of informal activities by Africans in the urban areas, political regimentation of Africans, migration control, etc.

By contrast, concession economies – the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Congo-Brazzaville, Gabon, Central African Republic, Rwanda and Burundi – relied on more brutal methods such as forced labour and plunder until late in the colonial period.

In the post-colonial period, regulatory attitudes set during the colonial period tended to persist. In some cases, subsequent events, such as long civil wars in Mozambique and Angola, or particularly severe economic collapse in Zambia and more recently in Zimbabwe, have shifted southern African economies toward higher levels of informal activity than were characteristic of other economies with similar histories.

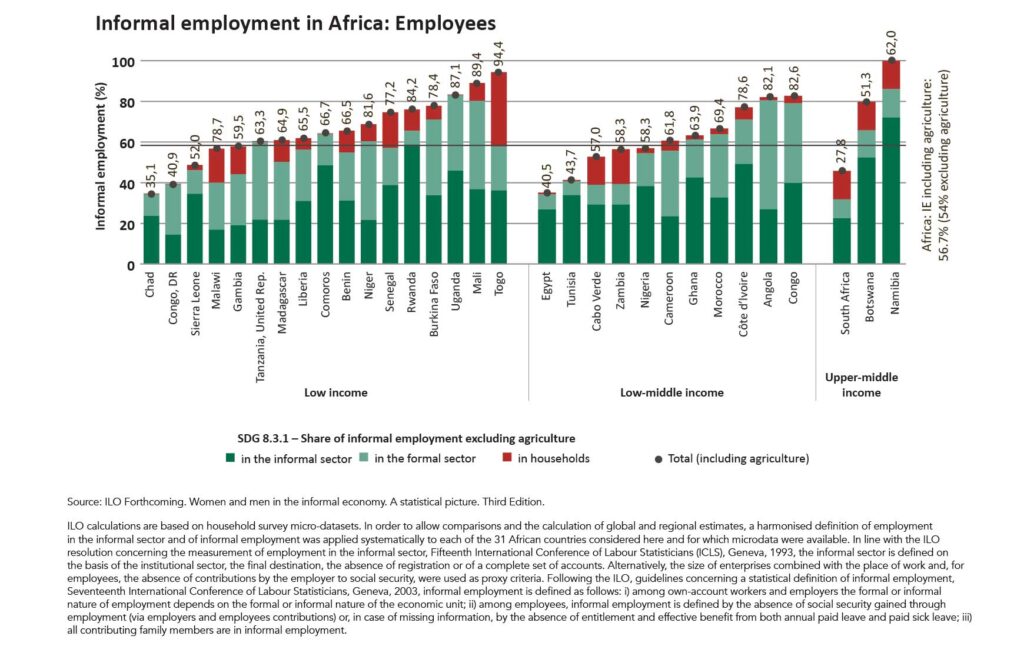

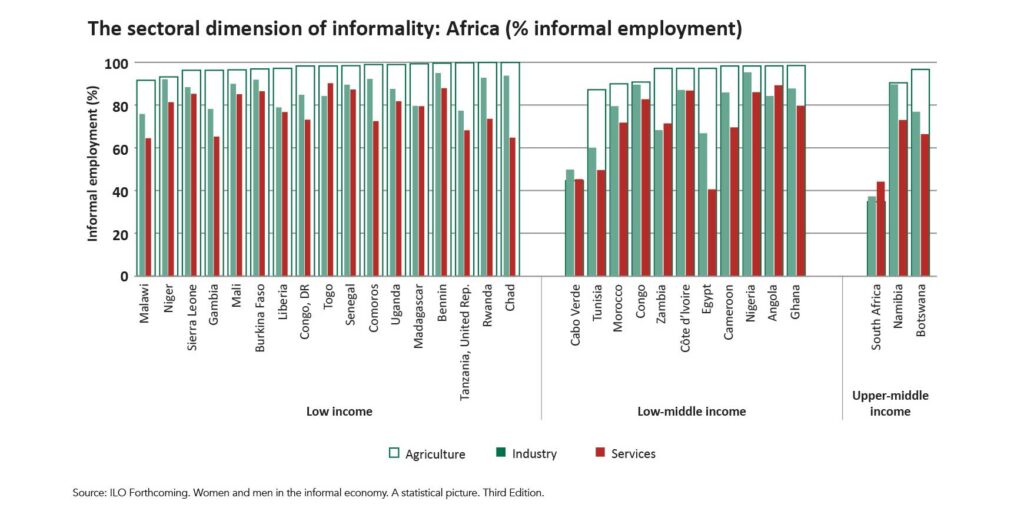

Drawing on ILO figures largely from the 1990s for informal activity as a share of the non-agricultural labour force, Mkandawire shows that levels of informal activity averaged 58% in West Africa, 49% in central Africa and only 19% in southern Africa. Despite the expansion of informality across the continent, more recent figures bear out a higher level of informality in West Africa than in East and southern Africa.

With appropriate caveats about the precision of these figures, and the large number of countries for which data on levels of informality is unavailable, recent measures of informality as a share of the non-agricultural labour force average over 65% in former cash crop economies concentrated in West Africa, and fall to 35% in the former labour reserve economies concentrated in southern and East Africa. There is insufficient data to calculate an average for former concession economies.

In the contemporary era, globalisation and economic reform have exerted more uniform influences among African countries, precipitating rising levels of informality across the continent. While historical differences in patterns of informality persist, contemporary push-and-pull factors shaping the expansion of informality have become more similar across countries and sub-regions within sub-Saharan Africa.

Researchers Henrik Huitfeldt and Johannes Jütting have identified four key drivers behind the contemporary expansion of informality. These are: slow employment growth in the formal economy, the restructuring of labour markets under liberalisation and globalisation, inappropriate formal sector regulations and competitive pressures to reduce costs.

This list of drivers tends to obscure the real dynamics of informal expansion. The reference to “slow employment growth” glosses over the active erosion of formal employment precipitated by market reforms, which has undermined employment generation through public sector retrenchment, de-industrialisation and import liberalisation. In the process, the restructuring of labour markets through liberalisation and globalisation has triggered an informalising “race to the bottom” with regard to wages and labour protection.

The third driver, inappropriate regulation, has been shown to be relatively unimportant to the expansion of informality in Africa and across much of the developing world. Greater deregulation of developing economies over the past two decades has been accompanied by expansion rather than contraction of informality.

In the context of Latin America, William Maloney noted the “paradox of a relatively flexible labour market accompanied by a very large informal sector”.

The fourth driver, competitive pressures driving down costs, is relevant, but has been exacerbated by liberalisation, globalisation and labour market deregulation.

The resulting picture of push-and-pull factors militates against the notion of informal sector expansion as a “voluntary” process. The image of voluntarism and choice presented by Maloney and others is not borne out by evidence from African countries. In particular, the widespread phenomenon of “straddling” – which refers to holding a formal sector job and carrying out one or more informal activities on the side – tends to undermine the notion of informality as a rejection of formal sector conditions.

Similarly, the idea that the desire to evade taxes pushes people into the informal economy is weakened by the fact that most informal actors pay a range of formal as well as informal taxes. Local government taxes are often collected by officials in the markets where informal actors operate or by sending revenue officers physically to other places of informal activity, making evasion difficult.

In some countries, decentralisation has also led to the delegation of collection of higher levels of taxes to local government authorities. Moreover, many informal actors pay a range of informal taxes, such as association fees, security levies to vigilante groups, and extra-legal levies for other forms of service provision (for instance, road repair and access to electricity). The idea that informality allows people to avoid taxes is a misrepresentation of reality.

In the African context, the major drivers of informality are less about choices to avoid unwanted taxes and regulations, and more about a lack of alternatives. Far from opting for informal employment, most Africans entering the informal economy are pushed by a lack of formal sector opportunities, as a result of global competition and the active downsizing of formal employment in the face of draconian economic restructuring. Across Africa, informal economic expansion is a product of massive public and private sector retrenchment, contracting access to land, as well as de-industrialisation and enterprise collapse in the context of liberalisation, devaluation and high inflation. The resulting escalation of unemployment and collapse in real incomes has led to a mass influx into informal activities as people struggle to survive in the absence of alternative employment or social safety nets.

Another restructuring-induced push factor involves the collapse of real wages, even among those who remain in formal employment. This has resulted in the intensification of “multiple modes of livelihood”.

On the one hand, multiple modes involves hanging onto formal jobs where possible while starting up an activity in the informal sector, such as informal taxi driving, trading, or selling services after hours. On the other, it includes the entry of previously non-employed household members, such as wives and dependants, into the informal labour market to make ends meet.

The pressures of economic restructuring have created two further push factors, including the weakening of markets for African formal sector firms, and consequent pressures to cut costs. Owing to the collapse in domestic purchasing power, weak export shares and the intensification of import competition, markets for many African domestic firms have all but collapsed.

Finally, the instability and unpredictability of formal institutions in the context of economic reforms has also operated as a push factor. In the face of incessant reforms in the formal economy over a period of three decades, many African economic agents have withdrawn into the informal economy where institutions are less subject to drastic and unanticipated changes.

Banking sector reforms and attendant bank failures in Nigeria, for instance, have frightened many successful informal operators out of the formal banking sector.

Constant reforms in regulations and tax regimes, rather than the regulations and taxes themselves, have also forced formal operators into the informal sector, where conditions are more predictable.

The negative influence of the changing regulatory environment was noted as long ago as 1999, when Poul Ove Pedersen and Dorothy McCormick observed that “continuous changes in rules and regulations and their inconsistent enforcement create an instability in the economic system which is not supportive of long-term investment”. While the informal economy has increased risk and instability for African consumers owing to the lack of legal protection and quality control, it currently represents a sphere of greater institutional predictability for many informal entrepreneurs.

Just as the push factors are more about compulsion than choice, the pull factors of African informal employment are more about default options than attractions. The fabled “ease of entry” of the informal sector is certainly a pull factor in that sense, since it only applies to the low-cost, low-income segments of the informal economy where livelihoods are most precarious.

More lucrative activities tend to have higher capital and skills requirements, and also involve informal institutional factors that limit entry, such as membership in associations or access to credit networks. As a result, women and the poor tend to be concentrated in saturated activities at the low-income end of the informal economy, rather than moving into activities with higher income potential.

A further pull factor involves the creation of new opportunities within the informal sector. Middle class demand for informal sector goods and services as formal options become unaffordable, and limited industrial sub-contracting to informal firms, have created a more skilled and lucrative niche within the informal economy.

In addition, the collapse of public services has opened up opportunities for informal service providers, including tutors, water sellers, and vigilante and private security services.

Foreign investors and multinationals have also contributed to pull factors into informality by drawing on Special Economic Zones (SEZs), labour brokers, and Bottom of the Pyramid (BoP) initiatives to create new informal rather than formal employment.

A final pull factor involves greater access to business support services and economic institutions in the informal economy. The social embeddedness of informal economic institutions makes them more predictable and accessible to African business actors, particularly those who lack the levels of literacy and the contacts to access formal skills training and business services.

However, this does not mean that the quality of informal services is better, only that they are more accessible. Levels of credit available through informal mechanisms are often too low for significant enterprise investment, particularly in the case of rotating credit groups. Similarly, the technical quality of informal skills training has become inadequate even for the needs of informal actors.

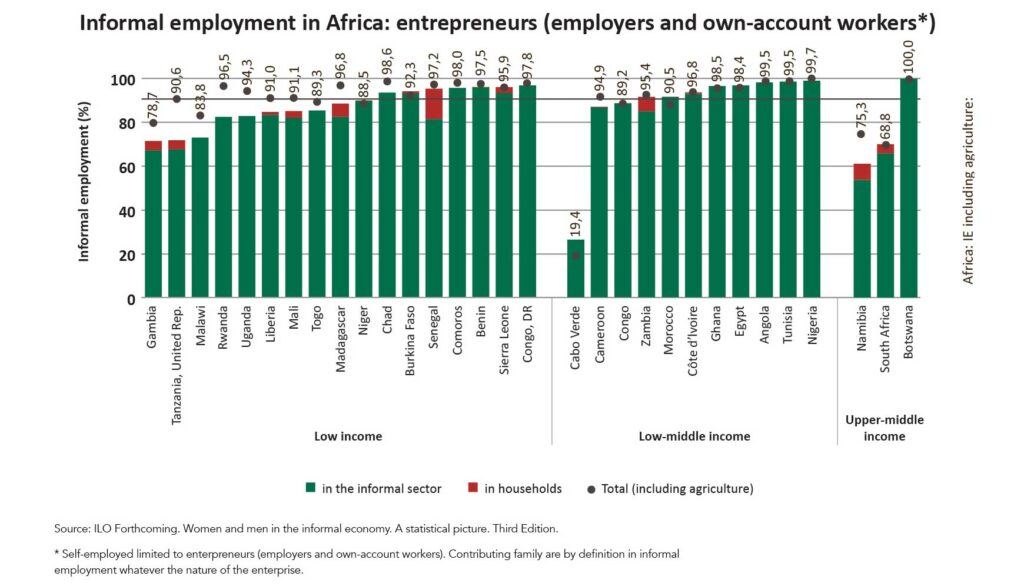

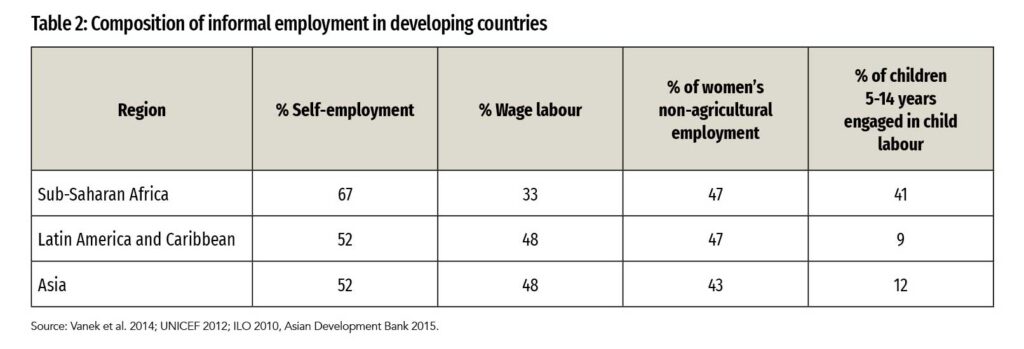

The composition and institutional organisation of African informal economies reflects the historical and contemporary factors outlined above. Contemporary statistical data indicates that African informal economies have the highest level of informal self-employment, accounting for 67% of informal employment (Table 2).

Conversely, levels of informal wage labour are comparatively low. While informal wage labour accounts for 48% of informal employment in other regions, it constitutes only 33% of informal employment in Africa. These statistics mask significant variation between West and southern Africa.

In West Africa, where informal entrepreneurship and large-scale trading networks have had more room to develop, informal wage labour tends to be below 20%, while in southern Africa and Kenya, levels of informal wage employment average over 50%, according to research by Jacques Charmes published in 2009.

Table 2 also reveals that women comprise 47% of informal employment in Africa. But 76% of African women working outside of agriculture earn their living informally due to lack of opportunity, making women highly over-represented in informality. Research shows that this is associated with female poverty rather than with increased income opportunities.

Africa also has the highest share of child labour in the world, with an incidence as high as 41% of children between 5 and 14 years of age. Child labour is particularly pronounced in West and central Africa, where apprenticeship institutions are stronger, informal employment of children in mines is widespread and domestic labour often involves younger girls than is common in southern and East Africa.

Understanding the contemporary dynamics of informal employment in Africa requires moving beyond the statistics to an understanding of the institutional organisation of informal employment. The institutional factors fall into three broad categories: institutions governing informal self-employment, those governing informal wage employment and new forms of informal employment arising from globalisation.

With regard to informal self-employment, the key factor to note is that informal enterprises do not constitute a mass of atomised operators. They are embedded in informal social and business networks through which they organise skills training, credit and business activities. These include ethnic and religious networks, rotating credit societies, informal trade associations and friendship or “old-boy” school networks.

This kind of informal self-organisation is referred to as “informalisation from below”. In some cases these informal economic networks are local, but in parts of Africa they have also had a regional and even international reach since colonial times or earlier.

Informal economic organisation underpins the effectiveness of informal actors in seizing new opportunities for self-employment, such as informal service provision in the face of collapsing public services. This informalisation of public services constitutes a kind of “poor man’s privatisation”.

The institutional organisation of informal wage employment is quite distinct. It involves apprentices and wage workers in informal firms, both casual and long term. These workers are increasingly linked to informal employers through wage relations rather than kinship or family ties. Informal wage employment absorbs those without the capital to start their own activity, comprising a growing share of informal actors who may never become independent.

Finally, new forms of organisation arising from globalisation include the transnationalisation of informal livelihoods, and informal employment in global commodity chains.

The transnationalisation of informal livelihoods refers to the increasing international reach of informal economic networks. The cross-border trading networks of the 1970s have been increasingly globalised. Ethnic and religious trading networks of West, East and even central Africa have penetrated deep into Europe, North America, and Asia since the 1990s.

Africa’s globalising informal economies are dominated by legal goods and services, including textiles, electronics and remittances. This “globalisation from below” links structurally adjusted African consumers into global markets via informal traders, and links informal manufacturing clusters into parallel commodity chains that produce and trade goods under the radar of the global economy.

Compared to other regions, informal employment in Africa is dominated by low-skilled, low-income activities with very limited connections to formal sector firms. This would tend to suggest that African informal employment offers little to the formal economy except unfair competition and a drag on productivity.

While these problems do exist, the increasing intertwining of the formal and informal economies, even in Africa, suggests that the informal economy offers some benefits to the formal economy as well. These benefits appear to relate largely to a search for cheap and flexible labour. Increasing practices of sub-contracting between formal and informal firms are blurring the boundary between informal self-employment and informal wage labour.

The growth of formal sector distributive sub-contracting to street traders, and outsourcing of ancillary services – canteen services, uniforms, repairs – to informal enterprises is turning informal enterprises into cheap labour for formal sector firms.

Sub-contracting between privatised urban service providers and informal water or waste services in poor areas is another means of turning informal firms into cheap labour for privatised service providers.

From this perspective, informality acts as a boost to formal sector productivity rather than a drag on growth.

Jütting and Juan R de Laiglesia, among others, have argued that expanding informality represents a “broken social contract” between society and the state. However, more questions need to be asked about how the social contract was broken, and what kind of measures are appropriate to reintegrate society and the state in the political and economic conditions of contemporary Africa.

Two different forms of relations between the state and the informal sector are evident in Africa, which have important implications for the future of the social contract. The first can be characterised as “instrumental”, involving a mutual evasion of responsibilities, as the state tries to shift the costs of reforms onto the informal economy and informal actors try to use public goods without paying a full range of taxes.

This form has become dominant in many African countries. While contemporary literature is very clear about the negative effect of this instrumental relationship on state fiscal and regulatory capacity, there is less attention to its negative effect on the organisational and absorptive capacity of the informal economy.

Declining incomes, social fragmentation and conflict are all indications of the unravelling of informal economic institutions under the strain of their “instrumentalisation” by donors, the formal sector, and the state. Moving down this path is leading to the destruction of the legendary resilience of African informal economies, increasing the vulnerability of societies to conflict, criminality and social collapse.

A second form of state-informal sector engagement can be characterised as “synergistic”. This involves the informal sector filling gaps in employment, social welfare and service provision in return for state investment in improving popular welfare and informal productive capacity. Properly synergistic relationships between the informal economy and the state can be found in many parts of east Asia.

There are also a number of countries in which the informal economy contributes to social integration and public investment in ways that have stabilised societies that would otherwise have disintegrated in the face of extreme economic pressure. Important examples include Senegal, a highly informalised but relatively stable democracy, and Somaliland, where the informal economy has contributed to reconstituting a state where even international efforts have failed.

Addressing the expansion of informality in sub-Saharan Africa requires attention to the specific nature of African informality. This includes a more highly informalised labour force than any other region, a predominance of self-employment over informal wage labour, a limited generation of new economic opportunities through globalisation, and the highest incidence among all regions of especially vulnerable sources of labour, including women, children and migrants.

Attention to locally appropriate models for rebuilding the social contract is vital to any measure to reduce informality. Current suggestions for rebuilding state-society relations through taxation and social protection offer a model more appropriate to societies with a high share of informal wage labour.

In many parts of Africa, where the bulk of the informal economy involves self-employment rather than informal wage labour, enterprise support and constructive linkages with the formal sector is key to reintegration with the state. An offer of pensions and unemployment benefits will do little to improve productivity, livelihoods or state legitimacy.

Where high levels of informal self-employment coincide with the weak bureaucratic capacity of former cash crop economies, as in West Africa, the organisational demands of workable social protection arrangements are more daunting than in southern Africa. Understanding the organisational realities of African informal economies, at the level of informal activities and in relations with the state and formal private sector, is vital to coming up with viable solutions to mounting poverty and precarious livelihoods.

This is an edited version of a paper first presented at REPOA’s 19th Annual Research Workshop held at the Ledger Plaza Bahari Beach Hotel, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania; April 09-10, 2013

This article first appeared in Africa in Fact, Issue #43, July – September 2017