Its skyline is dominated by the rail-served grain silos that are the cathedrals of the South African platteland (rural flatland). Ottosdal appears as a typical small town straddling a railway branch line, sustaining only one guesthouse and one safari lodge, and a small “country club” near the quarry outside of town.

The town originated as a Dutch Reformed Church parish in 1913 and was incorporated four years later. Inevitably, given the longevity of apartheid geography, this North West Province settlement of more than 800 registered residents in only 5,15km² still has a “black” township, Letsopa, and adjoining shantytown separated from the “white” town by the railway line.

Yet Ottosdal is unique, being one of a trio of small maize, sunflower, and peanut-farming towns falling under the Tswaing Local Municipality whose residents withheld their municipal rates and banded together to directly provide services to their neighbours – black and white – that democratically-elected local government was incompetent to provide.

In a country marred by continual and often violent “service-delivery” protests against corrupt, inept, and financially collapsing town councils, the actions of these autonomous, ratepayer-run towns marked a constructive – though hotly contested – attempt to fill a local governance vacuum.

Varied forms and degrees of autonomous municipalism have arisen across Africa, which we will examine here. Ottosdal has, alongside the neighbouring towns of Delareyville and Sannieshof, “been at the forefront of rates withholding in South Africa because of severe municipal service delivery failures,” according to a 2019 study on five such towns by Annette May and colleagues of the Community Law Centre.

In 2007, the three towns declared a dispute with the Tswaing authorities under three statutory acts relating to municipal financing and services, especially their collapsing water and sewage systems. But after losing in court, the towns embarked on a rates boycott of Tswaing, paying their rates instead to SIBU, a local affiliate of the National Taxpayers’ Union, which claims affiliates in 200 towns.

Delareyville is a larger 36.5km² municipality, laid out in 1914 with a current 10,000+ population and boasting a golf club, aerodrome, and maize mill, while Sannieshof is a 5,4km² town of 11,000+ that started life in 1928 as a post office village. Sannieshof also has an attached township, Asiganang, and an informal settlement, Pelhidaba, while Delareyville’s township is abutted by unincorporated shantytowns.

By 2009, a year in which the government admitted that 80% of the country’s municipalities had water and sanitation provision problems, the Sannieshof Inwoners Belastingbetalers Unie (SIBU), run by Sannieshof resident and florist Carin Visser, had “literally taken over the municipal government in Sannieshof. Financed by the residents, who pay SIBU (rather than Tswaing) for local services rendered, SIBU has become a municipality within a municipality,” according to a North West University study.

“The residents’ initiative managed to repair broken water systems and cleaned up the town,” the report said. “They also upgraded the town’s waste disposal site. In addition, they employed four workers and paid some outstanding accounts of Tswaing Local Municipality. In total, this had cost the ratepayers R163,000.”

It spent another R30,000 repairing a sewage pump in Asiganang township and R45,000 on a new pump for the waste-treatment works. “Essentially, the town was well-managed,” the report opined. SIBU had embraced the townships and informal settlements, and as its campaign “gained momentum, a sense of local patriotism took root” that crossed racial lines.

With all 25 North West municipalities reportedly on the brink of collapse, the provincial premier put the entire district under which Tswaing falls under provisional administration. Yet today, the sanitation crisis in Tshwaing is unresolved. At the same time, the 2022 municipal financial viability ranking conducted annually by independent analytical company Ratings Afrika showed 107 out of 112 of the country’s largest local municipalities and metros (cities) were on the verge of financial collapse.

Other forms of municipal autonomism in Africa include towns forced by conflict or government prejudice to sustain themselves; voluntary off-grid eco-communities; political decentralising experiments; the semi-autonomy of high-tech, free-trade zones; supposedly temporary refugee camps that entrench themselves with time; and even entire unrecognised countries with millions of inhabitants.

Involuntary withdrawals from governance include municipalities that have been starved of central state funding because of political hostility from the capital city, such as the Unita-run towns of central Angola in the aftermath of the war from 1992.

Angolan academic Paula Cristina Roque tells Africa in Fact: “In the province of Huambo, many areas… were run uniquely because the members had been trained by the rebel movement… They had their own way of functioning and setting up villages. They were starved of support because they were Unita, and that was for several years after the war.

“In some areas, in Cabinda,” [the enclave with a long history of secessionism that is separated from Angola by a sliver of the DRC] “and in the two Lunda provinces that are the poorest, most disenfranchised provinces, you would [still] find something like that.”

Other involuntary cases include towns in areas deliberately under-serviced by dominant ethnic elites because of their minority, immigrant, or marginalised populations, which is a widespread problem across the continent and the subject of monitoring by Accountability International, and a corrective programme by the African Alliance.

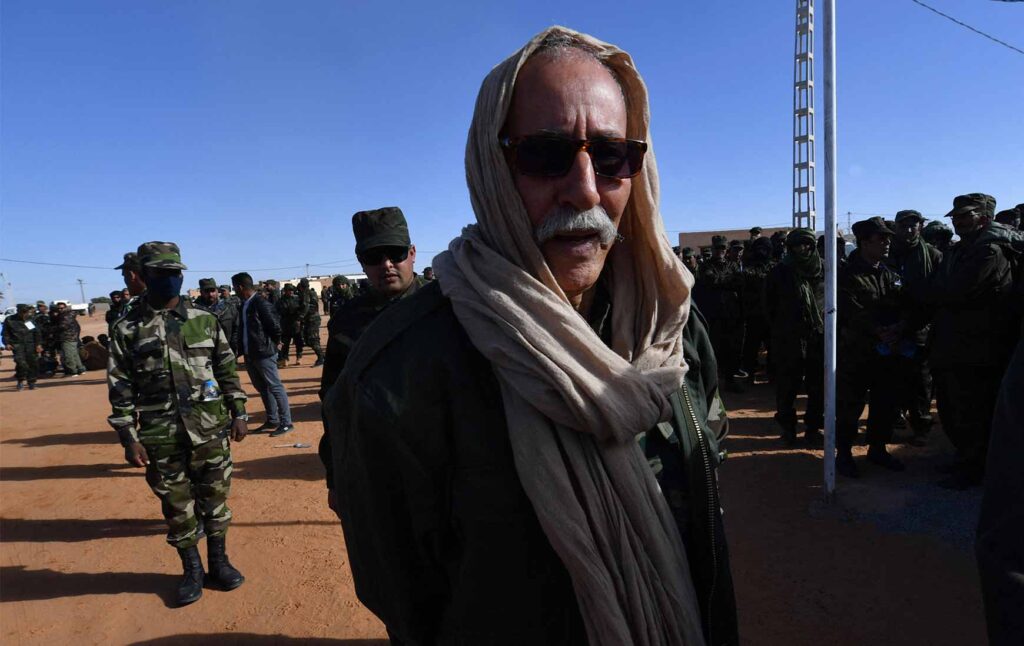

Some secessionist areas, like the third of Western Sahara run by Polisario, have consolidated over time as alternate administrations, while its tented refugee camps in Tindouf province, southern Algeria, established in 1975/6, have evolved into eight established, brick-walled self-administered towns.

Though Polisario’s Saharawi Arab Democratic Republic government-in-exile runs its affairs from the Roubani camp, the towns are divided into four districts consisting of collections of villages (daïras) made up of neighbourhoods (barrios). Local committees distribute goods, food and water, while education, culture, and medicine are administered at daïra level by barrio representatives.

But the most developed alternative administration in Africa is that of Somaliland, which seceded from imploding Somalia in 1991. Despite almost totally lacking international recognition, this territory of 176,120 km² has been moderately effectively run as a democracy since then, though it only decentralised governance from district to the local level in 2002. A study 10 years later by Abdirahman Adan Mohamoud in the capital Hargeisa noted that initially, “the functions of the municipalities were severely affected by serious power struggles that diverted the attention of local councillors and administration away from institutionalisation and service delivery. This was coupled with severely limited resources, institutional and capacity concerns, and legal framework issues.” Although local councils’ statutory mandate includes the “promotion of participatory planning and community participation in local decision making”, implementation is far from ideal.

Voluntary communities that retreat from governance, largely using ecological and new-tech subsistence methods, tend to be tiny, either based on dropout sub-cultures, religious sects, ethnic separatism (such as the controversial whites-only private town of Orania in South Africa), or the secessionist mentality of wealthy gated communities.

Photo by MARCO LONGARI / AFP)

A 2023 study on renewable off-grid mini-power solutions in sub-Saharan Africa by Nigeria’s University of Agriculture says mini-grids “managed by independent developers… constitute an autonomous model that provides a pathway to actualising a vision of an independent and self-sufficient supply of off-grid electricity to solve the problems of energy poverty.”

Political decentralising experiments that have all subsequently died on the vine since the 1970s include those of Libya’slocalist People’s Committees under Muammar Gaddafi’s “third universal theory”, and the “Ujamaa socialism” of Julius Nyerere’s Tanzania, which based its concepts on clan-centred village communalism.

“First,” Gaddafi wrote in his Green Book, “the people are divided into [some 600] basic [that is, local grassroots] popular congresses. Each basic popular congress” made up of sectoral interest groups such as syndicates, associations, and unions, “chooses its secretariat. The secretariats together form popular congresses which are other than the basic ones.” These representative inner-ring Popular Congresses in turn elect some 2,700 representatives to the General People’s Congress.

“Then the masses of those basic popular congresses choose administrative people’s committees to replace government administration. Thus all public utilities are run by people’s committees, which will be responsible to the basic popular congresses and these dictate the policies to be followed by the people’s committees and supervise its execution.”

People’s Committees – the local administrations – would then elect representatives to a General People’s Committee, which sat at national level alongside the General People’s Congress. Running from 1977 to 1993, the whole system was meant to be an exercise of living, direct democracy with the grassroots Basic Popular Congresses transmitting policy and action inwards via concentric rings.

But it was simultaneously an expression of corporatism in that all of society without exception was forcibly welded into a single instrument, and in practice, the General People’s Congress was a de facto legislature and the General People’s Committee an executive cabinet, while Gaddafi’s penumbral status as “Brotherly Leader and Guide” with no public functions, occluded the true central power he wielded.

Nigerian trade union activists Sam Mbah and IE Igariwey, in their assessment of African grassroots-democratic systems in their 1997 book African Anarchism, said Gaddafi’s proposals were “followed generally more in the breach than in practice”, while in Tanzania, the Ujamaa model failed because it had been used by Nyerere merely as a means of consolidating his political power among the peasant majority, with state bureaucrats, in line with World Bank and foreign aid strategies, controlling crop prices and dictating production targets, dragooning the peasantry and squeezing as much surplus out of them as possible.

On the opposite side of the political spectrum, in the case of free-trade zones, several studies indicate that to ensure efficiency, they are best run by entities that exercise financial and administrative autonomy from the usual phalanx of government agencies.

For instance, the UN Conference on Trade and Development’s 2021 Handbook on Special Economic Zones in Africa says that of the continent’s 237 such zones (SEZs), most are concentrated in Kenya, Nigeria, Ethiopia, Morocco, Egypt, Cameroon, Botswana, Uganda, South Africa, and Tanzania.

They have proliferated since the 1990s, with 43% state-owned, 41% in private hands, and 16% run by hybrid models, usually public-private partnerships. Given that these “zones are often large, integrated zones built as townships with residential areas and amenities”, many fall within the definition of towns for the purposes of this article.

The manual advises: “Best practice suggests that the SEZ authority should be an independent regulator governed by a board of directors with representatives from both the public and the private sectors… In all programmes [regardless of their ownership model] the board should be equipped with appropriate financial and administrative autonomy to shield it from political pressures as well as equip it with sufficient resources… Ideally, the SEZ authority should be conferred freedom in setting labour policies within SEZs – such as hiring, setting salaries and laying off workers. Taxation matters, such as establishing incentive packages, should also be delegated to the SEZ authority, if not provided in the SEZ law.”

Whether one is a small group of parallel municipalities as in South Africa’s North West province, a mid-sized autonomously administered high-tech zone, or a big constellation of supposedly community-participative towns as in Somaliland, it all comes down to: can self-management deliver?

Michael Schmidt is a Johannesburg-based investigative journalist who has worked in 49 countries on six continents. His main focus areas as an Africa correspondent for leading mainstream journals are emerging and high-end technologies, political developments, conflict resolution and transitional justice, and on the continent’s maritime and littoral spaces.