“They cut my nets, and the government does not do anything,” an outraged Somali fisherman named Yusuf told senior East Africa analyst Omar Mahmoud of the International Crisis Group. “If I take up a weapon to defend myself, they call me a pirate – but who is the real pirate?”

Mahmoud recalls this emotional encounter in a June 2024 article in which he warns of the resurgence of piracy off the Horn of Africa, where its original surge, from 2009 to 2012, was initially provoked by desperate local fishermen turning to armed robbery of the foreign vessels, hailing from nations such as Iran, India, and Taiwan, who were illegally fishing within Somali coastal waters and so depriving them of a livelihood.

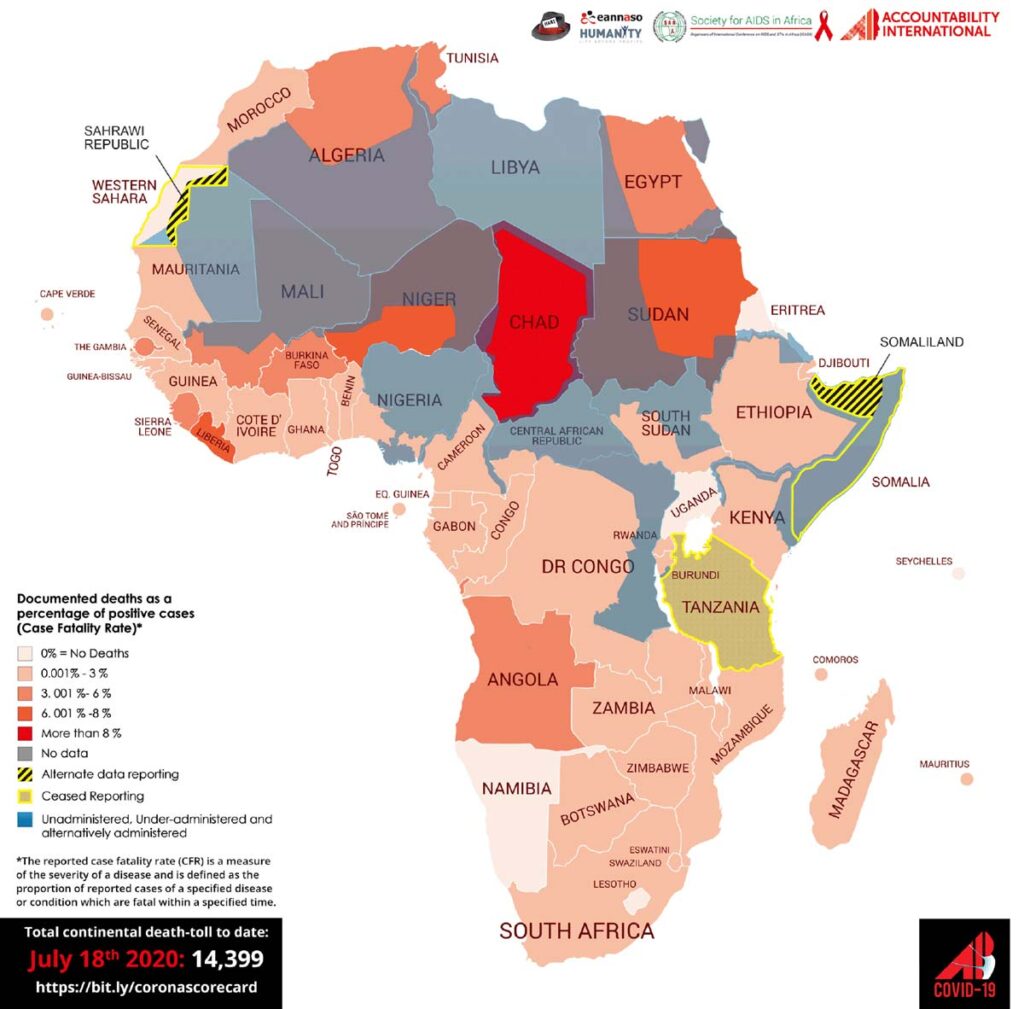

The scale of the damage to the coastal economy and fish stocks is huge: illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing strips an estimated $300 million of marine resources from the waters of the barely functional state of Somalia, its allied Puntland region, and the breakaway state of Somaliland every year (the continental total is $11.2 billion).

That narrative of fishermen’s resistance rapidly evolved; however, what could be termed subsistence piracy evolved into syndicate crime. Jessica Smith and Amadou Sy of the Africa Growth Initiative noted in 2013 that a kingpin would raise $50,000 from investors to purchase a “mothership” to venture far offshore. The kingpin would then carry skiffs crewed by well-armed pirates to seize foreign shipping – no longer only fishing competitors – and charge ransoms averaging $5 million to release ships and crews.

In response to that initial surge, the European Union (EU), NATO, and US naval anti-piracy patrols reduced piracy off the Horn to zero by 2020. However, maintaining that presence was expensive, so the International Maritime Organisation allowed civilian cargo ships to carry armed security squads. Yet continued insecurity for coastal fishing communities has seen piracy off the Horn soar again since 2023, while it has also become entrenched in the Gulf of Guinea.

The piracy saga sits at the nexus of three aspects that are crucial to the sustainability of Africa’s blue economy: maritime security, resources management, and community livelihoods.

Rights and duties on paper are exceptionally hard to enforce in vast oceans, and few African navies or coast guards have the capacity to rule the waves adequately; Somaliland has only one little coast guard motor boat and a few rubber dinghies.

But IUU fishing has surpassed piracy. According to a 2023 report from the Financial Transparency Commission (FTC), a non-profit network that monitors the global shadow economy, West Africa’s ocean is “a global epicentre for IUU fishing”, targeted by the top 10 IUU companies led by China’s Nasdaq-listed Pingtan Marine Enterprise Ltd and Spain’s Albacora SA (Pingtan refused to comment to the FTC, and Albacora denied the FTC’s assertion).

Nigerian Rear Admiral Adeniyi Adejimi Osinowo, a consultant on the Africa Integrated Maritime Strategy 2050, has estimated the cost of piracy and robbery at sea in the Gulf at $2 billion a year, while the losses attributed to IUU fishing there was estimated at US$1.3 billion a year. Both figures are the world’s highest.

But first, we need to appreciate the sheer immensity of what the African Union (AU) calls the African Maritime Domain. In a 2021 assessment by Vishal Surbun, the Pretoria-headquartered Institute for Security Studies (ISS) noted that the AU included inland lakes and waterways in this domain, yet that “in a world that looks increasingly to the oceans as a reservoir of resources, there is an underlying insecurity about growing human activity there. This insecurity arises from increased transnational organised crime; illegal, unreported and unregulated [IUU] fishing; environmental crimes and marine environmental degradation; disappearing biodiversity; and the effects of climate change.”

Rich in natural resources, Africa tends to be viewed by most observers in purely terrestrial terms, but its blue economy already generates $300 billion annually and sustains 50 million jobs, according to the American think tank Brookings Institution, and those figures are only set to soar.

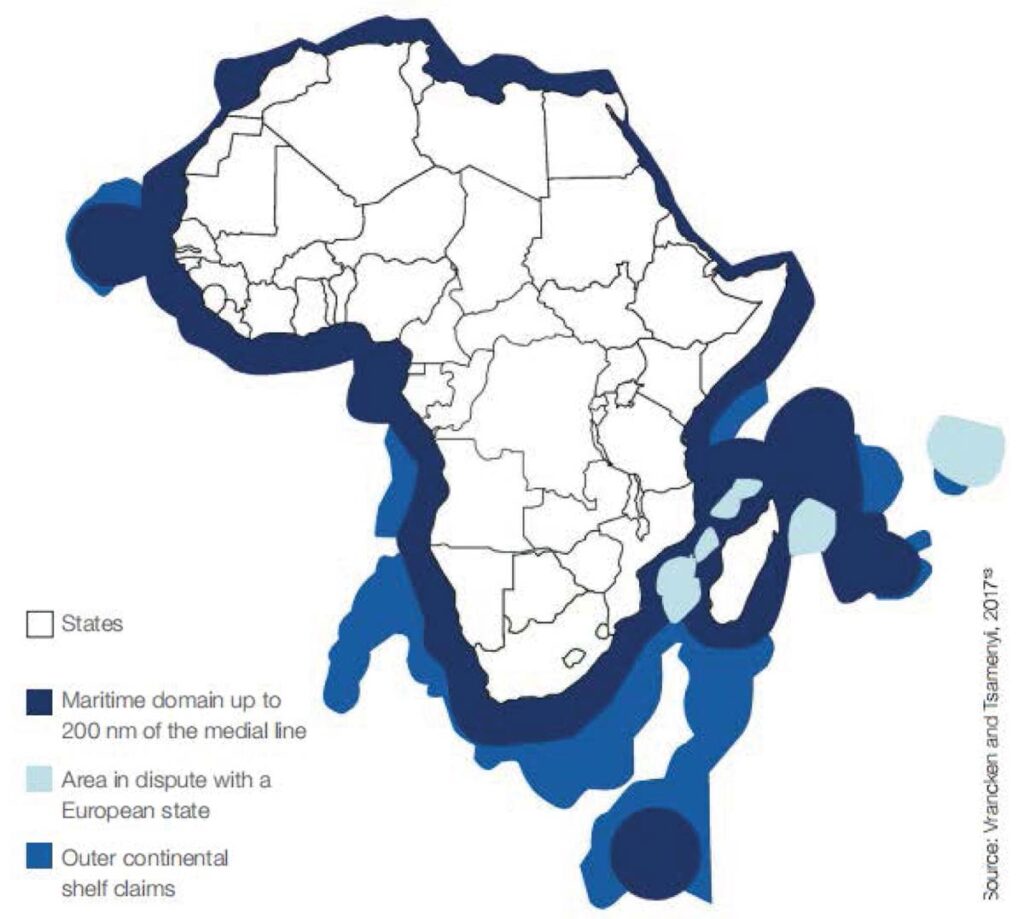

Forty African countries, including Somaliland as a de facto state and Western Sahara as a de jure state, have a combined exclusive economic zone (EEZ) totalling 13 million km2 – an astounding 42.8% of the continent’s land area.

Under the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, maritime nations’ rights and obligations are divided into several zones. Extending 12 nautical miles (22 km) out from shore are the territorial waters in which a state or territory has absolute sovereignty over the airspace, sea column, seabed, and subsoil – with the caveat that it has to allow for the “innocent passage” of foreign vessels. This is de jure national territory, and the coast guard, fisheries, customs, immigration, and naval vessels have full rights to police this zone.

From 12 nautical miles to 200 nautical miles (370 km) out is the state’s or territory’s EEZ, where its sovereignty is restricted to the sea column, seabed, and subsoil, all of which it may explore, manage, and exploit as it sees fit, again allowing for the passage of innocent vessels and the laying of communications cables, and for enforcement against those with criminal intent. Seas beyond the 200 nautical mile limit are the “high seas”, or international waters, where the nation has no jurisdiction.

And yet, if a country’s continental shelf extends beyond the 200 nautical mile limit, it may apply to the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf to extend their seabed and subsoil exploration and exploitation rights beyond their EEZ, to the edge of the shelf or to a maximum of 350 nautical miles (650 km) from shore. Such extensions do not allow a nation to fish in the water column, however.

As noted by Edwin Egede of the Cardiff School of Law and Politics, by 2022, 16 of Africa’s 40 maritime nations had made progress in submitting such claims, while another nine had started the process but were lagging behind. Africa in Fact calculates the total area claimed by 29 states – excluding Morocco and Comoros – at 5,051,902 km2.

An obstacle to unlocking the potential riches of Africa’s extended continental shelf is that many maritime neighbours lack delimitation agreements on their EEZs, which, as South African legal academic Siqhamo Yamkela Ntola has argued, affects any shelf claims.

In a 2017 report, Ntola detailed eight relevant delimitation disputes: Morocco/Mauritania; Benin/Togo/Nigeria; DRC/Angola; Namibia/South Africa; Madagascar/Mozambique; Madagascar/Mozambique/Tanzania/Comoros; Kenya/Somalia/Tanzania; and Puntland/Yemen. I will add the disputes between Morocco and Western Sahara, the latter’s maritime rights recognised in law by a 2017 European Union Court decision.

The situation is complicated by France’s colonial possession of Reunion plus four other islands in the Mozambique Channel; Mauritius secured Britain’s agreement in October 2024 to return the Chagos Archipelago, and most other countries have indicated to the UN that they would resolve their delimitations amicably, while others, such as Kenya/Somalia are before the International Court of Justice.

South Africa’s claim is probably the most dramatic, as, thanks to its possession of the Prince Edward Islands in the southern Indian Ocean, 2,160 km from Cape Town, it is the tenth-largest claim in the world. If the UN endorses its submission, it will make the country’s maritime holdings double the size of its land area and, as former Environmental Affairs minister Edna Molewa projected, create one million jobs and add $10 billion to the country’s GDP by 2033. Namibia’s claim at 1,066,426 km2 is likewise 1.2 times its land area, thanks to the extensive undersea Walvis Ridge.

Dr Ussif Rashid Sumaila, director of Canada’s Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries, has addressed African fisheries authorities before. He has told them what he states in his 2022 book Infinity Fish: that traditionally, fisheries’ and marine economists’ computations of fish (and by implication crustacean, seabird, and marine mammal) population sustainability focuses narrowly on the age and biomass of the single species each fishery exploits, thus ignoring that species’ role in the biodiversity of the entire local ecosystem.

Sumaila argues for an “intergenerational cost-benefit analysis” of fish stocks, looking at the benefits of restoring stocks to pre-collapse levels so that people a century from now will still have more than sufficient, “maintaining higher resource abundance at equilibrium”. This requires a long-term view of policy, regulation, monitoring, policing, and management. In particular, “capacity-enhancing” fishing quotas that drive overfishing must be strongly curtailed.

Fish stocks are a common pool resource in that fish belong to no one until they are caught. A system of authorities issuing individual fishing quotas (IFQs) as part of the total allowable catch is used to manage about 10% of the world’s fish stock. IFQs are tradeable in the same manner as carbon credits. But, as conflicts in West Africa have shown, aboriginal fishing rights and IFQs often clash. Sumaila stresses that littoral communities’ “social sustainability” is vital here.

“Global marine fisheries are underperforming economically because of overfishing, pollution and habitat degradation,” he writes. “Added to these threats is the looming challenge of climate change.” Rebuilding depleted and collapsed fish stocks would cost global fisheries about $203 billion over 50 years, Sumaila estimates, but claims that “it would take just 12 years after rebuilding begins for the benefits to surpass the cost”.

A key component of sustaining fish stocks is the creation of marine conservation areas, particularly in the spawning grounds of commercially-fished species. But most African maritime nations have been slow to create such protected zones, which are prmarily clustered off South Africa and its southern islands (with a target of protecting 10% of its EEZ), and the swathe of Indian Ocean between Mozambique, Madagascar, the Comoros, and Seychelles – with smaller enclaves off Tanzania, Kenya, Congo, Gabon, Guinea-Bissau, Senegal, Gambia, Mauritania, Morocco, Tunisia, and Egypt.

There are different ways to manage these areas: full sanctuaries in which no human impact is allowed; wilderness areas that tourists may visit, leaving a light footprint; and regulated take zones where catches are strictly limited by size, age, and species. But more is required, especially the management of “large marine ecosystems” such as the fish-rich Canaries, Guinea, Benguela, Aghullas, Somali, and Red Sea currents, which together generate 10 million tonnes of legitimate catch annually, and of long-distance migratory species such as whales.

All these involve managing fish stocks and other marine resources and eliminating effluent and pollution. This includes policing illegal waste dumping at sea and adopting greener technologies in the shipping and port sectors. In particular, green hydrogen fuel is being used to help decarbonise the global supply chain, with a focus on shipping corridors and harbours.

In March 2023, for example, in a first for Africa, a consortium of shipping, ports, and mining entities announced the establishment of a zero-emissions shipping corridor to move iron ore between Freeport Saldhana in South Africa and Europe; the free port itself was setting its sights on producing green fuels and using them in vessel construction.

The African Green Hydrogen Alliance, founded in 2022 by Egypt, Kenya, Mauritania, Morocco, Namibia, and South Africa, aims to make the continent the leading exporter of fuel and to give Africa a significant voice in global climate and energy dialogues (Angola, Djibouti, Ethiopia, and Nigeria have since signed on). African ports require international technical and funding assistance to go green, however, such as the UN’s project to support “sustainable smart ports”.

In 2009, the AU Assembly, concerned about maritime security, including piracy, illegal fishing and the dumping of toxic waste, called on the AU Commission to develop “a comprehensive and coherent strategy to combat these scourges”.

The result was the adoption of Africa’s Integrated Maritime Strategy (AIMS) 2050, consisting of “overarching, concerted and coherent long-term multi-layered plans of action that will achieve the objective of the AU to enhance the maritime viability for a prosperous Africa.”

One of the strategic objectives of the AIMS is the establishment of a Combined Exclusive Maritime Zone of Africa (CEMZA). But while the UN expects this and the African Continental Free Trade Area to increase maritime freight demand by 62%, the ISS’s Surbun cautioned that the CEMZA concept is vague on balance between national and collective rights and responsibilities, saying a huge amount of technical work on demarcation lies ahead.

Michael Schmidt is a Johannesburg-based investigative journalist who has worked in 49 countries on six continents. His main focus areas as an Africa correspondent for leading mainstream journals are emerging and high-end technologies, political developments, conflict resolution and transitional justice, and on the continent’s maritime and littoral spaces.