Kenya: security and sleaze

The country’s inability to protect itself from Islamic terrorists is directly linked to corruption

John Githongo—Kenya’s most famous whistleblower—does not mince his words: “We’re paying the price of corruption in blood.”

Mr Githongo, once the east African country’s anti-corruption czar and now the head of a grassroots governance group, is referring to Kenya’s recent security disasters: the deadly raids in June and July on villages along the Indian Ocean coast and the attack in September 2013 on the Westgate shopping mall in Nairobi, the capital. Although this violence is blamed on Somali militants, the Shabab, the country’s inability to protect itself is directly related to corruption, Mr Githongo says.

“The Westgate attack…leads us to question their ability to protect us,” he says of the government. “The systems that are meant to protect us have been corrupted.”

Mr Githongo knows this issue first hand: during his 2003-2005 watch as the presidentially-appointed anti-corruption chief he uncovered a massive $777m procurement scam involving 18 contracts for a variety of security-related goods. Passport printing technology, a forensic laboratory, and other equipment included in the contracts might have helped the government control who enters its borders and could have been useful in identifying the Somali gunmen who terrorise the country.

This scandal—known by the name of one of the ghost companies involved, Anglo Leasing—hit the headlines again in May when two of the foreign companies implicated in the scam successfully sued for breach of contract in European courts. The Swiss and UK court rulings compelled President Uhuru Kenyatta’s government to pay a total of $16m to these shadowy firms.

The payment created huge outrage among the public and members of the op- position parties. With the wealth of evidence provided by Mr Githongo, was paying-up not avoidable, Kenyans asked?

Mr Githongo, 49, a bear of a man with a fondness for loud shirts that emphasise his massive chest, does not hesitate to denounce the culprits: “Looking at the papers, the documentation we’ve seen, it seems [the Ken- yan government] lost the cases deliberately,” he says.

The Law Society of Kenya has tried to block future payments, but their appeal has been denied. Hundreds of millions of dollars remain at stake if another of the implicated companies goes to court to recover unpaid debts.

Opposition leader Raila Odinga claimed in June that the Anglo Leasing scam has cost the taxpayer over $300m to date in payouts and over-priced loans. The architects of the scandal have yet to be prosecuted. Kenya has blocked international attempts to investigate it: in 2009 the UK’s Serious Fraud Office had to suspend its investigations of Anglo Leasing because the case “depended on mutual legal assistance from the government of Kenya”.

Mr Githongo, who returned to Kenya in 2008 after fleeing death threats related to his exposé of the procurement scam, remains determined to break down the net- works of civil servants, politicians, businessmen, lawyers, bankers and auditors linked to organised crime. Sitting behind a simple desk in a largely empty room, Mr Githongo works two phones, an iPad and a computer at the offices of the Inuka Kenya Trust, the organisation he set up to advocate for good governance in Kenya. As well as running this NGO, he personally speaks out against issues as varied as wildlife crime, drug and human trafficking and slavery.

“In this globalised age, the grand corruption networks skimming off road con- tracts use the same networks as the people doing money laundering and drug traffick- ing,” he says. Kenya is in danger of losing its wildlife, “something we hold in trust for the whole of humanity”, because of these systems, he says emphatically.

Corruption has flowed through Kenya’s veins since colonial times. In 1956, seven years before independence, Harold Whipp, an engineer, committed suicide on a rail- way line near Nairobi after he was implicated in a years-long construction scam, writes David Anderson in his 2005 book “Histories of the Hanged”.

In the 1980s it moved Peter Eigen, then retiring director of the World Bank in east Africa, to set up an organisation dedicated to fighting corruption, giving birth to Transparency International. Mr Githongo, formerly a journalist, was the country director of Transparency International from 1999 until 2003. That year, Mwai Kibaki, a new president with promises to end sleaze and graft, appointed him Kenya’s anti-cor- ruption czar.

Despite a new president elected in March 2013, corruption at the top has deep- ened, Mr Githongo laments.

In March a government project aimed at providing every schoolchild with a laptop was suspended by the Public Procurement Administrative Review Board because the company that won the bid does not manufacture computers. Also in March, the president shunned competitive bidding to award a $3.6 billion railway contract to a Chinese construction company that is on the World Bank blacklist for corruption. Both deals remain bogged down by controversy. While the laptop deal is on hold, rail con- struction looks set to plough ahead.

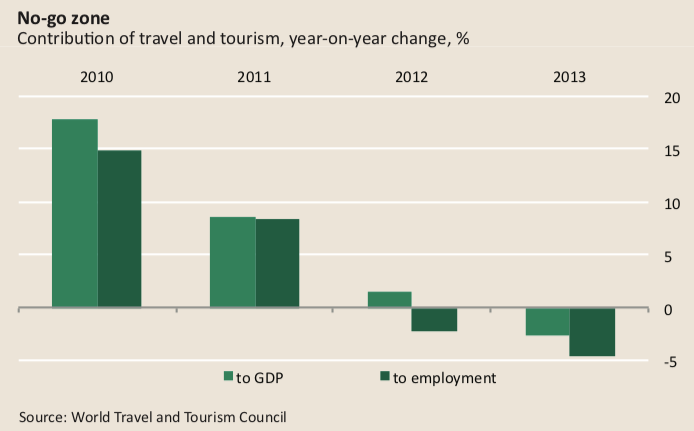

The graft is inextricably tied to insecurity, Kenya’s most visible problem. The two issues are short-circuiting the nation’s economy. Tourism is faltering. It accounted for 12.1% of Kenya’s 2013 GDP, compared to 13.7% in 2011, according to the World Travel and Tourism Council, an industry lobby group.

The attack on the Westgate shopping centre, which left at least 67 dead, shook the nation. Kenyans and expats alike started avoiding popular shopping centres. Tour- ism received a further blow in May when Australia, Britain, France and the US updated their travel advice to warn against all but essential travel to Mombasa, the country’s number-one tourist destination.

Mr Githongo recounts a recent dinner at the upmarket Junction shopping cen- tre in Nairobi. “I said, ‘Let’s go to Junction. No one will be there because everyone is scared,’” he says with a mischievous smile. He and his dinner companion queued for 50 minutes to get into the car park as security officials made exhaustive checks on passengers and vehicles. When they arrived at the restaurant, sure enough, it was empty. “They’re taking a very big hit because of this security issue,” Mr Githongo says. “It’s having a direct [impact] on us economically, socially, politically.”

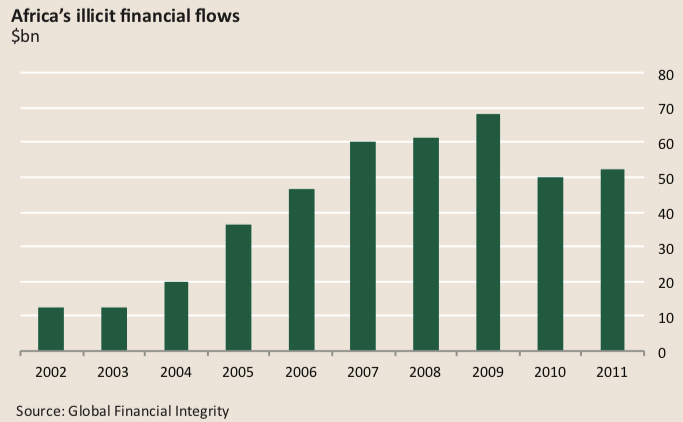

David Cameron, the UK prime minister, championed offshore transparency at the G8 summit in June last year in an attempt to crack down on graft and tax evasion in developing countries. Illicit flows from Africa were $52 billion in 2011, according to Global Financial Integrity, an American research group. This was the equivalent of 5.5% of the continent’s GDP of $954 billion, according to the World Bank.

What good might the $777m that was destined for the procurement scam have achieved, had it actually been spent on improving security services?

In response to the Westgate attack, Kenya’s Somali community has suffered extortion and violence by the police, whose mandate should be to protect them. “Somalis are scapegoats in Kenya’s counter-terrorism crackdown,” was the title of an Amnesty International report released in May.

A 2009 biography of Mr Githongo, “It’s Our Turn To Eat” by Michela Wrong, documents his journey as a whistle-blower. It is an alarming account of how tribalism reinforces corruption as clannish elites vie for a fatter share of the cake.

Kenya, infamous for its ethnic divisions, is now experiencing religious discord. “If we hadn’t ‘eaten’ all those security contracts, I wonder whether we’d be having the same kind of security operation now that is profiling members of the Somali community and Muslims, and really causing sectarian divisions in Kenya that had not existed there in the 50 or 60 years of independence?” Mr Githongo asks. “Once you go down the road of sectarian division, coming back is extremely difficult.”