The efforts of liberation movements spearheaded by leaders such as South Africa’s Nelson Mandela and Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah inspired hope as African countries gained their independence from colonial rule. However, post-independence, corruption in many forms became a formidable barrier, hindering Africa’s journey towards prosperity and stability. This article explores the multifaceted nature of corruption in Africa and offers strategies for addressing it and fostering sustainable development.

While corrupt practices are often misconceived as solely occurring within the public sector, the enabling role of KPMG and other prominent auditing firms in South Africa’s state capture scandals underscores the pervasive nature of corruption, revealing that even oversight bodies can succumb to pressure from powerful interests. In South Africa, the global firm was accused of deceit and collusion that cost the country’s economy dearly. Various publications have estimated the projected cost of the KPMG-facilitated state capture agenda to be between R500 billion and R1.5 trillion.

Angola’s history of a close relationship between government and business elites has led to conflicts of interest and corruption. Despite its rich natural resources, the country still has a high poverty rate of 15.1 million people, with a poverty threshold of $1.90 per day. Particularly concerning were the scandals involving Sonangol, the state oil company, which was granted a monopoly over offshore oil exploration in 1976.

In June 2016, former President José Eduardo dos Santos appointed his daughter, Isabel, as the CEO of Sonangol. This appointment raised serious concerns about conflicts of interest, as she wielded significant political influence and controlled other companies involved in Sonangol’s operations. Once dubbed the richest woman in Africa by Forbes, dos Santos’s empire crumbled after her father stepped down from power and now faces corruption charges in Angola, with hundreds of millions of dollars now frozen in several jurisdictions.

If anything, this narrative underscores the risks associated with unchecked political power and the lack of accountability in government institutions, leading to economic corruption and the misappropriation of public resources for private enrichment.

In Mozambique, European bankers, Middle Eastern business interests, and members of the country’s political elites collaborated in 2013-14 to arrange a $2 billion loan to the country, ostensibly to develop its fishing industry. The so-called “hidden debt” scandal, in one of the world’s poorest nations, had disastrous consequences for the country. The loan was secured by undisclosed government guarantees and kept secret from the IMF and donors. The only benefit to the country was in bribes to implicated officials.

A 2021 report by the independent Swedish research institute CMI succinctly summed up the monumental scale of this corrupt project and the real cost to Mozambique and its people: “Donors and lenders had kept the country afloat, and they pulled the plug. The IMF halted its programme, and donors cancelled direct budget support and other aid to the government – a reduction of $831 million in 2016 compared to the year before. The cascade that followed included a fiscal crisis, making the government unable to pay its bills. There was a major currency devaluation, foreign debt became unpayable, the economy slowed down sharply, real GDP per capita fell, unemployment soared, and poverty increased.”

This case highlights how corruption, a pervasive global problem, often arises from collaborations spanning various sectors such as business, finance, and politics. It flourishes in settings characterised by a lack of transparency and accountability. Mozambique’s misappropriation of funds also exposed weaknesses in government oversight and its financial systems.

The widespread impact of corruption on a global scale emphasises the necessity for concerted cross-border initiatives to combat it effectively. Africa’s health sector is another area where corruption hurts the poorest. In sub-Saharan Africa, maternal and infant mortality rates remain significant challenges. Projected for 2030, it is estimated that 390 women will die in childbirth for every 100,000 live births, which is more than five times higher than the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) target for that period. Similarly, the region’s infant mortality rate stands at 72 deaths per 1,000 live births, far above the reduction target. These alarming statistics underscore the urgent need for improved healthcare services.

Corruption exacerbates these challenges, particularly in public healthcare sectors. In Malawi’s Kamuzu Central Hospital, a study by Annette Mphande-Namangale and Isabel Kazanga-Chiumia in 2021 found that 80% of patients and their guardians were aware of informal payments for health services, with 47% admitting to making such payments. A staggering 87% of these payments were made at the request of health workers themselves. This highlights a widespread issue whereby patients feel compelled to make payments outside official channels.

In 2009, Zambian health ministry officials embezzled SEK7 million in Swedish (about $671,809) in aid, leading a whistleblower to report the theft to Zambia’s Anti-Corruption Commission. The scandal disrupted Sweden’s health programme in Zambia and highlighted the difficulties donors face in enforcing zero-tolerance anti-corruption policies in the health sector. The result is vulnerable communities suffer, and patient care and access to essential services is compromised.

The enduring impact of colonialism in Africa is also evident in governance systems that prioritise resource extraction and exploitation over sustainable growth and prosperity. This legacy has fostered systemic corruption and mounting debt, which impede some African nations’ ability to attract foreign investment. Political instability, stemming from colonial legacies, exacerbates corrupt practices by creating opportunities for exploitation. Weak governance systems and fragile institutions, with frequent leadership transitions, exacerbate the problem.

Zimbabwe exemplifies this scenario, particularly in its economic landscape, where about 40% of its population lives in extreme poverty. The country also grapples with a substantial debt burden, amounting to $17.2 billion, with 74% attributed to external debt. Repayment of these debts is further complicated by accrued arrears and penalties, reaching a staggering $6.6 billion, including $2.01 billion in penalties as of December 2021. Political instability, bureaucratic red tape, and rampant corruption exacerbate these economic woes, with Zimbabwe ranking 149th out of 180 countries in corruption perception.

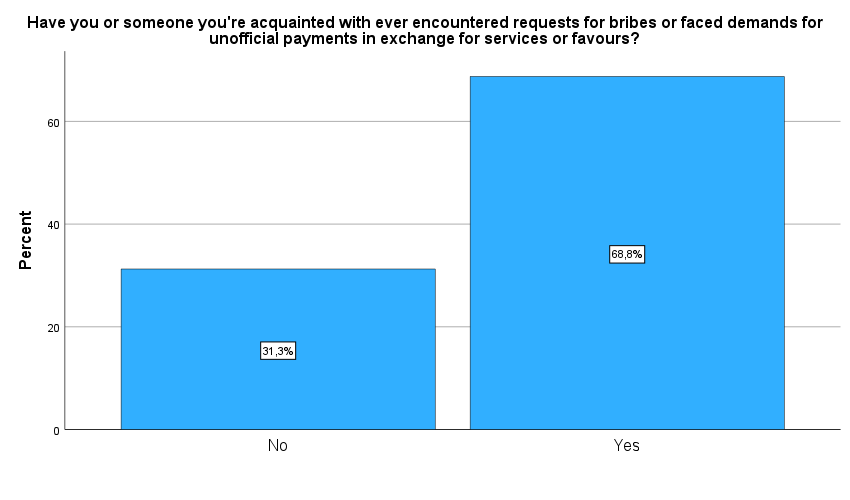

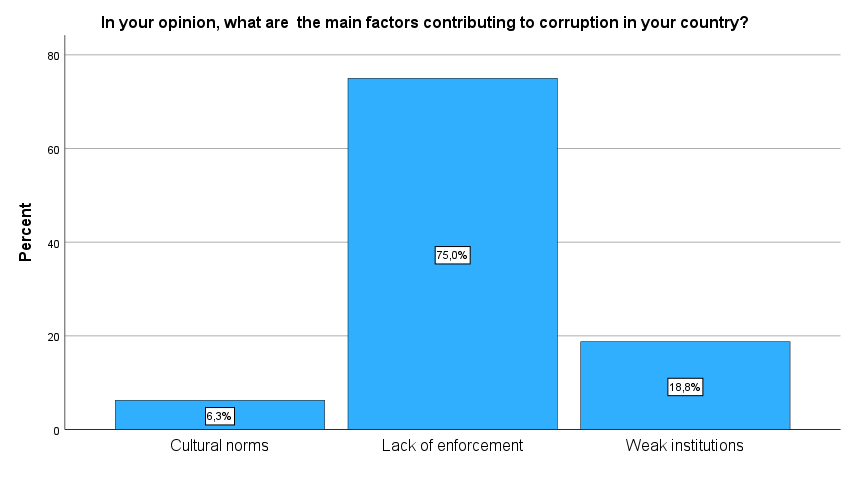

Addressing these challenges requires comprehensive reforms to strengthen governance, promote transparency, and foster stability, ensuring a brighter future for Africa’s development and prosperity. The author, a researcher currently pursuing a PhD in corporate governance at the University of the Western Cape, conducted a survey of 6,400 participants in two southern African countries in February this year, which yielded significant insights into corruption prevalence and perceptions. Lesotho represented 43.8% of participants, while South Africans constituted 56.3%, offering a diverse national sample. Findings showed widespread awareness of corrupt practices, with 68.8% reporting encounters or knowledge of bribery requests. Key factors contributing to corruption included “lack of enforcement” (75%), “weak institutions” (18.8%), and “cultural norms” (6.3%). These results underscore the need for targeted interventions to combat systemic corruption, enhance transparency, and foster accountability within the surveyed group. (Tsabo, 2023).

It is imperative to outline comprehensive strategies aimed at combatting corruption, which clearly remains a significant obstacle to progress and development. Firstly, political leaders must exhibit unwavering dedication to fighting corruption, not only through rhetoric but also through concrete actions and policy implementation. This commitment should be transparent and consistent to earn the trust of their citizens.

Secondly, a collaborative approach involving both the government and the private sector is essential. By working together, these entities can pool resources, expertise, and influence to implement effective anti-corruption initiatives. This collaborative effort can enhance transparency, accountability, and oversight across various sectors, thus reducing opportunities for corrupt practices.

Furthermore, it is crucial to empower citizens to uphold integrity and actively participate in anti-corruption efforts. Drawing inspiration from individuals like South Africa’s former Deputy Finance Minister Mcebisi Jonas, who bravely exposed corruption, citizens should be encouraged to report corrupt activities and hold their leaders accountable. This citizen engagement can foster a culture of transparency and ethical conduct, further bolstering anti-corruption measures.

Additionally, both local initiatives and global support are vital components in the fight against corruption. To effectively combat corruption, African leaders must prioritise anti-corruption initiatives within their countries with the support of international organisations and allies who offer resources, expertise, and diplomatic pressure.

Finally, establishing accessible whistleblower platforms and conducting widespread awareness campaigns are instrumental in educating citizens about their role in combating corruption. By providing avenues for reporting corruption anonymously and raising awareness about the detrimental impacts of corruption on society, these initiatives empower individuals to take a stand against corrupt practices and contribute to building a more transparent and accountable governance system.

Tholang Tsabo

Tholang Tsabo is currently pursuing a PhD in corporate governance at the University of Western Cape, building upon his prior MBA obtained from Unisa. Engaged in multiple capacities, he contributes to municipal audit committees and disciplinary boards, leveraging his expertise in finance to ensure effective financial oversight. Additionally, he holds the position of Director at BK Chartered Accountants, where he focuses on audit, accounting, and advisory services.