Côte d’Ivoire’s emerging SMEs

The government is focusing on small business to diversify the economy

Once the economic powerhouse of Francophone west Africa, Côte d’Ivoire has suffered decades of crisis. Now the world’s biggest cocoa producer is turning the tide on more than 30 years of economic hardship caused by conflict, draining structural adjustments, the devaluation of the regional currency and the tumbling cocoa price.

From independence in 1960 to the 1980s, Côte d’Ivoire’s economy flourished from its fertile farmlands, which produced cocoa, coffee and palm oil. Those government-controlled sectors funded gleaming skyscrapers in the capital, Abidjan, and paid the salaries of the civil servants who worked inside. Building a diversified economy, however, was not a government priority during these years.

In the last decade, the country’s land has yielded other natural resources: oil, gas and gold. But Alassane Ouattara, who took the presidential reins in 2011 after a six-month post-electoral crisis that left 3,000 dead, is trying to move the country beyond natural resources and agriculture. He is counting on creating a mixed economy that will extinguish political tensions.

One of Mr Ouattara’s first moves as president was to apply an emergency stim- ulus package, mostly funded by foreign donors such as the IMF and France. Since then, Côte d’Ivoire’s GDP has expanded, growing 9.8% in 2012, 8.7% in 2013 and an estimated 8.0% in 2014, according to the IMF. This package targeted five priority areas: water, health, education, electricity and sanitation. It included repairing and reconstructing infrastructure that was destroyed during the 2010-2011 post-electoral conflict. It also had a peace-building side that included the education and re-integration of former combatants.

But now, economists foresee that GDP growth may slow down unless these quick fixes are replaced by a longer-term strategy tackling the Ivorian economy’s structural flaws. In particular, the country’s dependence on cocoa makes the economy vulnerable to fluctuations in this commodity’s prices. To curb 30 years of growing poverty, one of the main goals of the government’s strategy is to strengthen small and medium enterprises (SMEs), a unique strategy in a region where economic policies usually favour large corporations and ignore small businesses.

So far, development and economic wonks, especially those from the Bretton Woods institutions, have praised the policies of Mr Ouattara, a former IMF director. The country reached 79th place out of 160 countries on the 2014 World Bank’s logistics performance index, the highest ranking of any Francophone African country. Although its business environment still has a long way to go, it is improving. Côte d’Ivoire jumped six places in a year, reaching the 167th position out of 189 countries in the World Bank’s 2014 “Doing Business” report, but still lags behind countries like Afghanistan and Syria.

Jean-Louis Billon, president of the Ivorian Chamber of Commerce from 2002 to 2011, knows business challenges. He left the private sector in 2012 and since then has worked as the country’s commerce minister, an expanded portfolio that also includes supervising small business.

“An economy can be competitive only if it allows its SMEs to innovate, to supply big companies, to safeguard its exports and to contribute effectively to the GDP,” he told Africa in Fact. “In Côte d’Ivoire we have emphasised plantations and big enterprises. But 90% of Ivorian businesses are SMEs. This should be the cornerstone of our development,” Mr Billon explained. “Côte d’Ivoire cannot develop and build a solid economy if it does not maintain a large pool of SMEs.”

Small companies represent about 98% of Côte d’Ivoire’s formal businesses and create 23% of the country’s jobs, according to the ministry.

This is not to say that small businesses did not emerge under the unchallenged rule of President Felix Houphouët-Boigny from 1960 to 1993. “During the Houphouët- Boigny era, civil servants were encouraged to buy land and, in a way, to start their own small businesses,” explained Marcel Benie Kouadio, an economist and dean at Abidjan Private University. “This allowed the rise of a middle class. But it was not formal and more of a hobby. Above all, it was not sustainable. One would employ the brother-in-law or the nephew to manage the land. It was additional revenue, but it was not a true generator of employment.” It provided the government with little tax income.

Under Mr Billon’s guidance, the Ivorian government has launched several initiatives to make SMEs a vital part of the formal economy. It has adopted a law that strengthens SMEs’ legal protections and makes bank loans easier to obtain; updated laws protecting and regulating investments; created a new commerce court which fast tracks disputes at a lower cost than the existing judicial system; slashed fees by 50% for importing tools and production equipment; and introduced several initiatives to connect entrepreneurs to funders, notably an investment forum held in January 2014 that brought pledges of $930m of foreign direct investment into Ivorian businesses.

In addition, the government has made massive expenditures in infrastructure, allocating about $6 billion to roads and a second port terminal in Abidjan. Several pro- jects also aim at boosting energy production from 1,391 megawatts (MW) in 2011 to almost 4,000MW by 2020.

The Investment Promotion Centre in Côte d’Ivoire (CEPICI, after its initials in French) is the government’s main measure to ease business life for entrepreneurs. This agency, headquartered in Abidjan and with three offices in the economic centres of Bouaké, San Pedro and Yamoussoukro, is a one-stop shop: in a few hours and in a single place, business owners can fill out documents such as business and tax registration, customs agreements, etc. The government is expected to respond to all applications within a month.

These procedures took nearly a year under the previous government. More importantly, they provide more transparency to help curb corruption. Last year, 2,535 new businesses, mostly SMEs, were registered, about 18% more than in 2012, according to CEPICI figures, which are not always reliable.

The CEPICI “simplifies everything”, said businesswoman Marie Diongoye Konaté, who has run a grain food-processing company since 1994. Like many busi- nesses begun before Mr Ouattara became president, Ms Konaté’s company, Protein Kissé-La, was not registered and therefore did not exist legally. She took advantage of the new system to register and to raise capital. After spending one hour submitting her documents to the CEPICI, the government responded in 21 days, approving the registration of her agro-industrial business.

Her case is similar to that of many of the businesses in Côte d’Ivoire that struggled under the corruption and intimidation prevalent during the previous government. With 71 employees, her firm is an example of how a good business plan and a strong understanding of local realities can compete with foreign giants such as Nestlé and Danone. “Business is picking up,” Ms Konaté said. “We have the feeling that things are moving forward after a decade of difficulties. The government has, so far, adopted several measures that make our life easier.”

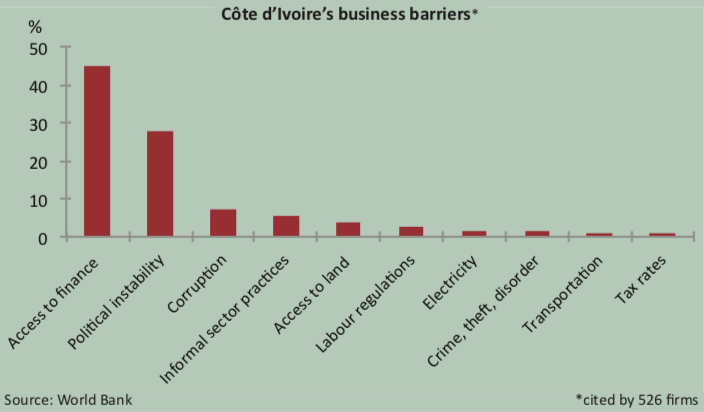

Despite the government’s new policies and the investment forum’s momentum, SME owners still face several difficulties, particularly in raising capital, explained Joseph Amissah, the director of a small-business group. Banks and other funding institutions do not provide enough guidance and are reluctant to take risks, he said.

But alternatives to a wary banking system are emerging. Thierry N’Doufou is the CEO of Siregex, a 20-month-old high-tech company with ten employees. In May 2014 it launched an educational tablet for Ivorian classrooms that should be available soon in neighbouring countries. It has succeeded by overcoming major investment obstacles. Finding the funding was the hardest hurdle. “Ivorian bankers did not understand the project,” explained Mr N’Doufou. “We succeeded in earning the trust of certain persons and investment funds to secure the project.” (Mr N’Doufou, however, would not share the names of his investors.)

In addition to the difficulty of raising capital, the country’s “heavy fiscal burden” is impeding the development of SMEs, said Jean Kacou Kiagou, president of Côte d’Ivoire’s General Business Council, an association of business owners. The government’s taxation policies deter investments and encourage companies to relocate to neighbouring countries such as Ghana, with fewer fiscal constraints, he said last March. Businesses represent 90% of the Ivorian government’s tax revenues, while the African average is about 40%, according to the OECD, an intergovernmental think-tank.

Fiscal pressure and the absence of funding need to be tackled together, according to the commerce minister. This is the goal of an upcoming government programme, which plans to improve managerial skills and teach companies how to participate in a competitive environment. “SMEs are crucial to fight against unemployment and poverty,” Mr Billon said. “It is a government priority.”

Investors in Côte d’Ivoire, for the most part, are still holding their breath: political reconciliation from the bloody post-electoral crisis has yet to become a reality. The next presidential elections are in 2015. Firm economic growth may only take place once the troubles are definitively over.