At night, Nigeria’s commercial capital, Lagos, is a study in contrast. Half of this West African city’s homes are swathed in tropical darkness. The other half are lit by the city’s only reliable source of power – petrol and diesel generators.

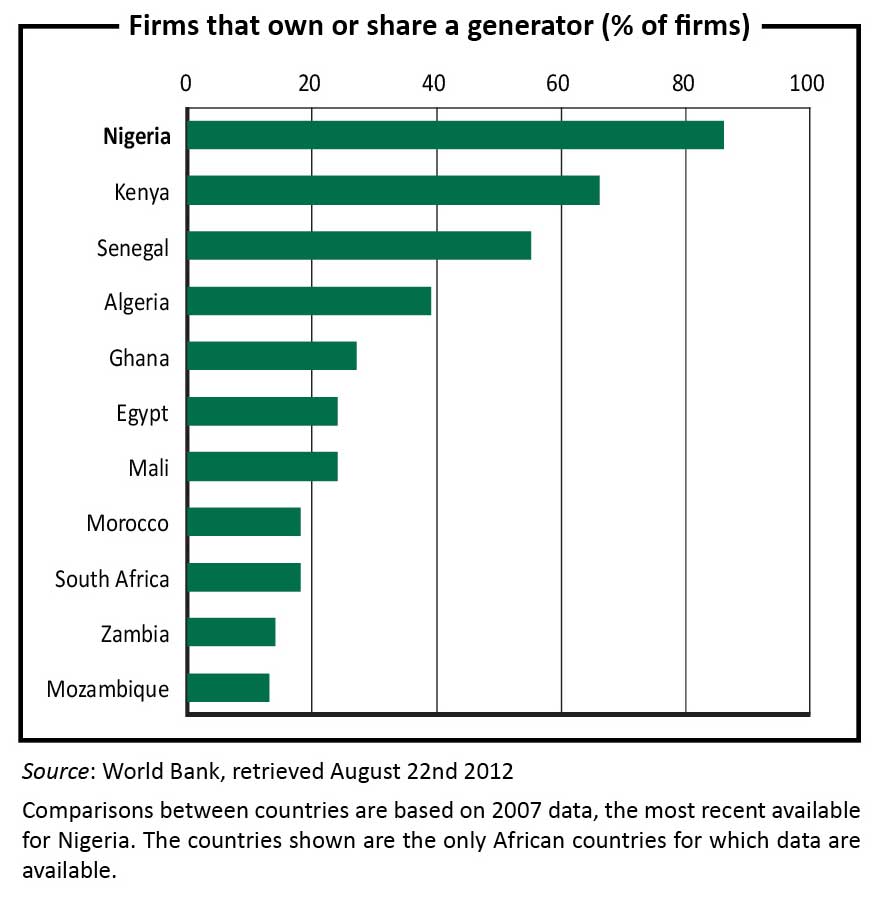

As it is in Lagos, so it is in the rest of the country. Across Nigeria, privately-owned generators serve as alternatives to the sputtering state electricity firm, the Power Holding Company of Nigeria (PHCN).

“An estimated 60 million residents use generators of varying sizes. In the last year, average residential expenditure in fuelling power generators climbed to an all-time high of about $13.35 billion per annum,” Frank Jacobs, a senior official of the Manufacturers Association of Nigeria told Vanguard, a national daily.

A recent study by the Nigerian Customs Service, which awarded Nigeria the dubious honour as the continent’s biggest importer of generators, says private entities spend $8 billion to import generators each year.

Such is the ubiquity of generators in this country of 160 million people that experts have argued that its constellation of privately-owned diesel and petrol generators produces more electricity than all the state-owned plants.

In 1999, the country’s power plants generated a measly 1,500 megawatts (MW) at their peak, failing to meet a national demand of 4,500MW. Conversely, experts estimate that petrol and diesel generators produced 2,400MW.

A little over a decade later, Nigeria’s population had risen by tens of millions and demand was oscillating around 20,000MW. Supply from the public mains in 2010 was at best marginal (about 2,500MW). Independent sources estimated that private generators could provide a whopping 28,000MW of electricity.

Millions of Nigerians rely on the country’s ageing national grid that is served by three hydroelectric and six thermal plants with a total generating capacity of 5,951MW. However, years of neglect, poor maintenance, corruption and bad governance have stripped the power plants’ capacity.

Nigeria’s electricity infrastructure declined during the 1970s when the oil boom pushed up the country’s real exchange rates which then drove up imports, throttled the manufacturing sector and strangled the country’s formerly strong culture of maintenance.

As Nigeria’s population exploded in the following 20 years, the demand for electricity also soared, but investment in infrastructure shrank. A study by a Nigerian law firm, Kusamotu & Kusamotu, would later show that between 1989 and 1999, no major investments were made in the power sector. By the turn of the 21st century, only a quarter of the country’s 79 individual units were generating power.

The energy sector’s travails transcend generation. Electricity travels long distances in Nigeria, moving through cables strung over huge expanses of Sahel desert and heavy forests. Theft and decay often go unnoticed. When theft is detected, investigations are rarely conducted. When decay is discovered, repairs are often long in coming. The result: substantial watts of electricity are lost in transit. Recently, the Transmission Company of Nigeria, the country’s national electricity distributor, announced that more than 30% of energy produced at power stations was lost during transmission.

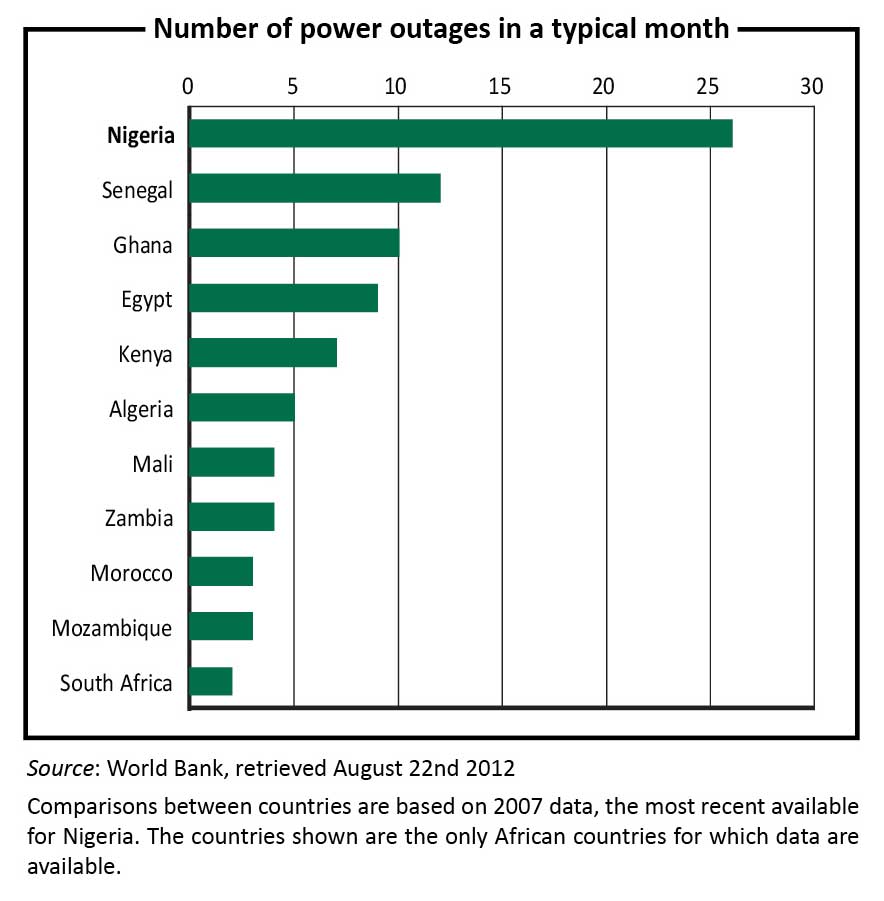

Across Nigeria, blackouts are the rule rather than the exception. Sustained power cuts run from days into weeks and in some areas into months. The Council for Renewable Energy, a Nigerian non-governmental organisation, estimates that the country loses $797 million to power outages annually.

The effect of Nigeria’s power crisis on its development is deleterious. A 2010 government report highlights the link between socio-economic development and the availability of electricity.

“Over the past two decades, the stalled expansion of Nigeria’s grid capacity, combined with the high cost of diesel and petrol generation, has crippled the growth of the country’s productive and commercial industries,” according to the report. “If this situation were to persist, the cost by 2020 in terms of lost GDP (gross domestic product) would be in the order of 20 trillion naira ($130 billion) every year. It has stifled the creation of the jobs which are urgently needed in a country with a large and rapidly growing population; and the erratic and unpredictable nature of electricity supply has engendered a deep and bitter sense of frustration that is felt across the country as a whole and in its urban centres in particular.”

Manufacturers and service companies lament that huge expenditure on alternatives to the country’s undersupplying mains perennially raises production and other costs. In recent years, as manufacturing concerns have struggled to cope with the high costs of production, several factories have closed and businesses have relocated to Ghana, Nigeria’s better-managed western neighbour.

Telecommunications, the country’s second biggest sector after oil and gas, has been hit hardest.

“Self-provision of power supply is expensive,” the former head of MTN Nigeria, Ahmad Farroukh, told a gathering in Lagos in 2007. “We spend close to 700m naira [$4.4 million] on diesel per month.” All the operators in the country use two sets of generators, dubbed master and slave, to ensure smooth, non-stop operations, he added. An industry source estimates that 9,000 generators power cellular base stations throughout the country.

At the bottom of the distribution chain, consumers complain that corruption compounds the problem of insufficient energy. At a recent consumer forum, Lagos resident Akin Adeyemi railed that state power firm officials would not provide him with an electricity meter that he had purchased.

“These people are terrible,” Mr Adeyemi said. “I paid for a meter but they won’t give it to me. They put me on [an] estimated bill. Every month I get ridiculous bills. I can’t even count the number of times I have been to their office. Really, [I] am tired,” an evening paper, PM News, quoted him as saying.

What should Nigeria do to escape this bind? The World Bank suggests pumping $300 million per year into the power sector for the next 10 years. President Goodluck Jonathan’s government has also touted a 350 billion naira ($1.93 billion) super grid as a panacea.

Funding is not the primary problem. The country’s power failure persists because successive governments have failed to plan adequately and tackle corruption. In the past decade, Nigeria has spent almost $20 billion to revamp its electricity.

In 1999, the administration of former President Olusegun Obasanjo set the rather ambitious goal of leap-frogging Nigeria into the league of the world’s 20 leading economies by 2020. The plan was to increase capacity to 100,000MW each year.

The government ordered scores of thermal power plants and then discovered that the state gas firm had sold several years’ supplies in advance. Eight years later, generation had increased only by 600MW, up from 2,000MW.

In the twilight of Mr Obasanjo’s administration, it was discovered that 13 imported electricity-generating thermal barges could not leave the Lagos port because planners had not factored in the special equipment needed to transfer them upland. Later, a parliamentary investigation would reveal that most of the funds budgeted for power projects ended up in the pockets of the politicians, legislators and technocrats.

Currently, Nigeria is in the throes of yet another reform bid: a contentious privatisation drive that is bitterly opposed by the unions. The Jonathan administration must find ways to meet the demands of the unions, whose stubbornness has stalled the privatisation programme for years.

The Jonathan administration has split the former power monopoly, PHCN, into a transmission firm, 11 power-generating companies and six distribution companies. To attract foreign investors, tariffs have been raised by more than 80% and funds have been released to pay off the former monopoly’s 34,000 workers.

Little will be achieved, however, if Nigeria does not tackle the corruption that has crippled the sector for decades. At the moment, there is little to deter corrupt officials from stealing the massive funds that the government is pumping into the sector.

While there are no silver bullets, experts agree that the Nigerian power problem can be fixed. The government, working with multinational companies, must maintain gas supplies to the country’s new thermal power plants. Insufficient gas supplies are pushing some of the new thermal plants to operate far below capacity, while a recently purchased plant has not even been fired up at all.

Indeed in March, when generation dropped by 900MW, Nigeria’s minister of power, Bart Nnaji, blamed insufficient gas supplies. Experts have said that a more efficient gas delivery system would add 1,500MW to the national grid.

Finally, Nigeria’s eight power research institutes should focus on developing affordable, alternative energy sources. A long-term power strategy could include subsidies for community initiatives that harness renewable energy. One day, clean and cheap power could light up the other half of Lagos at night.

This article first appeared in Africa in Fact, Issue #4, September 2012