Kenyan complacency

Young activists believe it is time for Kenya’s middle class to grow up

In February this year, Kenyan artist and activist Boniface Mwangi led a march through Nairobi asking Kenya’s middle class to grow up. Banners shouted the march’s theme—“Diaper Mentality”—and 50 giant polystyrene babies bobbed on the shoulders of protesters decked out in the red, black and green of Kenya’s national flag.

Mr Mwangi, 31, a well-known photographer, created a series of satirical photographs to accompany the protest showing educated Kenyans dressed as babies, happily accepting the status quo, which includes government corruption, police brutality and impunity for sexual abuse.

“Kenyans need to grow up,” Mr Mwangi said before the march in the offices of PAWA254 (an amalgam of “power” in Swahili and the Kenyan international dialling code). He founded this NGO in 2010 to promote art as a vehicle for social change. “Let’s stop behaving like kids and take responsibility for our actions,” he said, while sitting in his third floor office with murals depicting Nelson Mandela, Bob Marley and Kenyan environmental activist Wangari Maathai.

After the 2011 Arab spring uprisings, journalists, analysts and academics were quick to ask whether the ferment would spread south. Would the failure of governments to meet the rising expectations of the newly prosperous and educated result in political turmoil in sub-Saharan Africa as it had in the Arab world?

Africa has the fastest growing middle-class in the world, according to a 2012 report by Deloitte, a global accounting firm. The African Development Bank, defining “middle-class” as anyone who spends between $2-$20 per day, estimated in 2011 that 45% of Kenyans belong to the middle class. A report this year by South Africa’s Standard Bank suggested that this figure was misleading: it found 83% of Kenyans still live below the poverty line. But the report concurred that the Kenyan middle class is expanding rapidly. The number of middle-income households in Kenya has grown three-fold in the last 25 years, from 130,000 to 400,000 people, according to Standard Bank.

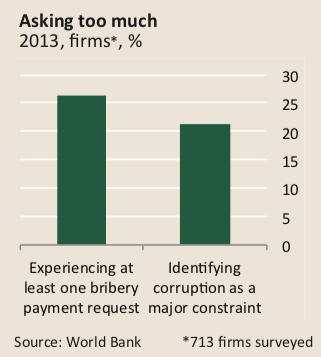

Despite many of the same conditions that led to the Arab revolts, comparable uprisings have not erupted in Kenya or in Africa. Kenya, for example, is the world’s fourth most corrupt country, according to Transparency International (TI), the Berlin-based watchdog. Official bribery and corruption cost the economy billions of dollars a year, according to insiders, including finance ministry officials who told parliament in December 2010 that almost a third of the national budget ($4 billion) was lost to corruption annually. Procurement scams and bribes for contracts remain commonplace, while seven in 10 people bribed a public official last year, according to TI.

At the same time unemployment and inflation make daily life for the average Kenyan a battle to survive. Of working age youths, 60% are unemployed, according to the United States Agency for International Development. Food prices are rising; year-on-year inflation was over 8% in August, according to government figures. Muggings, physical violence and rape are prevalent: a third of Kenyan women and one in five men were victims of sexual violence as children, according to a 2010 survey by UNICEF, the UN’s children’s agency.

So why have the swelling ranksof Kenya’s middle-class citizens not stood up to their leaders to force political change—or at least demand more accountability?

One reason is that the country’s electorate is divided by ethnicity and not by socioeconomic issues. For example, after Mwai Kibaki’s controversial victory in the 2007 elections, over 1,000 people were killed in ethnic attacks pitting Kikuyus, the community to which Mr Kibaki belongs, against ethnic Luos and Kalenjins.

Another explanation is that Kenyans fear the police’s heavy-handedness in dealing with protesters. Mr Mwangi’s generation grew up under President Daniel arap Moi, whose government arrested, beat and tortured political dissidents. A bank clerk who watched the “Diaper Mentality” protest from the sidelines admitted he had been brought up afraid to protest. “It’s too risky,” said the clerk, who spoke on condition of anonymity.

Before Mr Mwangi and his fellow protestors—numbering about 200—could enter Uhuru Park (“freedom” in Swahili), an open space adjacent to Nairobi’s central business district, riot police attacked them with tear-gas and batons. Screaming protestors discarded the polystyrene babies.

“We protest but we’re not moving forward,” Mr Mwangi said later that day, announcing he would no longer organise protest marches. “It doesn’t change anything.”

Other young activists lambast the Kenyan middle class for not engaging with politics. One, Shamit Patel, 28, who took part in the February march, accused the middle class of “complete apathy”. “They earn enough money to have a good lifestyle,” he said. “And they’ll still complain, don’t get me wrong: but that’s all they’ll do.”

Mr Mwangi agrees. He has reached the conclusion that “Kenya’s middle class” does not even exist. You have only the “extreme wealthy” and the “poor”, he said.

“The lifestyle is termed middle class because they’re able to spend some time at weekends drinking and blow some cash on nyama choma[“grilled meat” in Swahili],” Mr Mwangi added. “But they’re not really middle class. If they lost their job, they’d go down to being the poorest,” he said.

Definitions of middle class range from the ADB’s consumption brackets to categorisations such as education, occupation or ownership of durable assets, preferred by social and political scientists, to Mr Mwangi’s self-styled behavioural indicators such as those who pay $1.50 for a cup of coffee.

Kenya’s situation is best understood though a focus on durable assets, he said. The “pretend middle-class”, as Mr Mwangi calls them, do not own property or cars. They drive hire-purchase vehicles and pay high rents because punitive interest rates (over 16% on average this year, according to Nairobi-based estate agency, Hass Consult, which produces quarterly market analysis for Kenya) make mortgages unaffordable.

“I pretend that I am middle class, that I’m able to maybe spend some cash, send my children to private school,” he said. “But that means that if I didn’t have a job, and if I did not get a job in the next three or four months…I go back to living in the slums.”

Mr Mwangi has accepted that street protests, such as those that shook the Arab world, are not the way forward for Kenya. He is now determined to drive change via political means. The elections in 2017, the next opportunity for Kenyans to exercise their democratic voice, will mark the beginning of this process, he said. He wants to see Kenyans reject tribalism and partake in issue-based politics that call leaders to account.

Instead of asking educated Kenyans to come onto the streets, he will ask them to forgo the occasional pricey coffee and put their money towards financing change. He and his friends, including some returning from the diaspora, will start a “movement”, he said. And he will ask Kenyan citizens—especially those who think of themselves as middle class—to finance it.