Côte d’Ivoire’s crippled opposition

The main opposition party in this west African nation is barely standing

With Côte d’Ivoire’s presidential elections slated for November 2015, and the country still recovering from the violence that followed the last polls in 2010, the role of the former ruling party and now the main opposition is anyone’s guess.

The Ivorian Popular Front (FPI) ruled this west African nation for ten years under the stewardship of Laurent Gbagbo, its founding father and the country’s former president. Large blue posters of Mr Gbagbo smiling and wearing sunglasses festoon the FPI headquarters in Abidjan, the capital. In large white font, the headline of these placards reads: “Still standing”.

But this is no longer true. Mr Gbagbo is now behind bars at The Hague charged with crimes against humanity, including murder, rape and persecution. He faces a trial at the International Criminal Court (ICC), which is still not scheduled. These charges stem from his refusal to concede defeat in the November 2010 presidential elections and the brief but bloody civil war that followed. It ended when French forces captured Mr Gbagbo in April 2011.

Since then, the Popular Front has been in disarray and has refused to participate in politics. This withdrawal, known as an “empty chair” political strategy, is the FPI’s way of expressing its discontent with the current government led by Alassane Ouattara, who won the 2010 presidential poll. It is unhappy with what it deems the government’s harsh treatment and one-sided justice reserved for FPI members. At the time, this strategy may have seemed politically expedient, a stalemate of silence between the FPI and the Ouattara government. But in the end this play may lead to the checkmate of this once powerful party.

The Popular Front is divided. A minority are in favour of dialogue with the government, but the majority has dug in its heels and refuses to cooperate. In October 2011 the FPI ordered the boycott of the legislative elections held that December. Two years later, the FPI again refused to participate in the 2013 municipal and regional elections.

More recently, in September 2014, the FPI announced suddenly that it would recall its representative from the newly elected Independent Electoral Commission (CEI). It disputes the neutrality of the CEI’s president-elect, Youssouf Bakayoko, who had headed the commission in 2010. Shortly after the polls closed that year, Mr Bakayoko declared Mr Ouattara the winner at Mr Ouattara’s campaign headquarters. But an hour before, the head of the Constitutional Court had declared his close friend, Mr Gbagbo, the winner. This appearance of bias from both sides unleashed a five-month civil war that left 3,000 dead and more than 150 women raped, according to Human Rights Watch.

While the Popular Front’s withdrawal from the CEI will not affect the electoral commission’s work, it considerably diminishes hopes for reconciliation between these political parties. The FPI’s absence from the election management body close to a year before the November 2015 presidential polls also reflects its struggle to find a new vision and move past grievances to reconcile with the Ouattara government.

“If we want peace and reconciliation in this country, we have to examine the causes before their consequences,” said Michel Amani N’Guessan, a Popular Front vice-president and former defence and education minister. “The Ouattara government has judged Gbagbo’s partisans unilaterally.Both Laurent Gbagbo and Charles Blé Goudé [head of the FPI’s youth wing] are currently at the ICC and none of Ouattara’s people can be found there. This is partial justice.”

Mr Ouattara has attempted to appease the opposition party by liberating Popular Front political prisoners, Mr N’Guessan admitted. But he has only freed 100 of the 800 FPI members behind bars, “a drop in the ocean” while “the arrests of FPI partisans continue on a daily basis,” he added.

Human Rights Watch and the Ivorian Human Rights Movement, a local NGO, were unable to confirm the exact number of FPI detainees. Both groups confirmed that Mr Ouattara planned to release more in the coming months.

The Popular Front began an internal reorganisation in July hoping to “reinvigorate and rejuvenate the party”, said the party’s president, Pascal Affi N’Guessan (not related to Michel N’Guessan). It has filled 200 party positions with younger and more highly educated partisans.

The Popular Front’s efforts to recover its former strength have been bumpy and full of challenges. Its deep internal divisions are the major threat to its longevity and have significantly diminished its prominence in Ivorian politics.

With presidential elections a year away, the Popular Front must step up its game. In September it received a symbolic slap in the face when the head of the Democratic Party of Côte d’Ivoire (PDCI), Henry Konan Bédié, threw his party’s support behind Mr Ouattara. Even though the ruling party—the Rally of the Republicans (RDR)—and the PDCI have long been political allies, this official announcement further pushes the FPI to the sidelines of Ivorian politics.

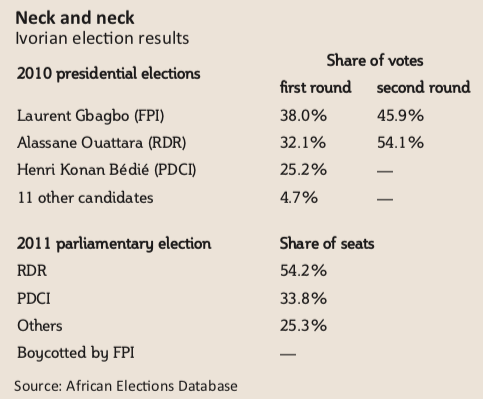

Should the FPI decide to boycott the 2015 elections, Mr Ouattara will surely win another term and the Popular Front will fade into oblivion. Should the FPI decide to run, the electorate will perceive their participation as a strong sign of national reconciliation. Victory, however, will not be easy. The party won 38% of the votes in the first round of the 2010 presidential elections and 45.9% in the second round.

Leaving such a big chunk of the electorate without a choice will not help Côte d’Ivoire’s citizens put aside their differences. “The FPI’s participation in the 2015 electionswill allow Ivorians to put the sad events of 2010 behind them,” said Wodjo Fini Traoré, a human rights activist. “The FPI’s refusal to participate in the upcoming elections would be disastrous for Côte d’Ivoire. Everybody needs to participate. We want the electoral process to be as inclusive as possible.”

In December, as this magazine was going to press, the FPI General Assembly was set to convene to decide if they will name a candidate in the 2015 presidential elections.

For months, “Gbagbo or nothing!” has been the main slogan of the Popular Front hard liners. If the party wants a future and an actual seat at the negotiation table, it might have to find a new motto and fill that empty chair.