Burkina Faso: out with the old

Will opposition parties work with the military in the transition government following the departure of Blaise Compaoré?

Burkina Faso was recently rocked by massive protests that led to the resignation of long-serving president Blaise Compaoré and an army-led transition.

As this magazine was going to press it was unclear who would form the transition government that the army had promised to put in place. Under Burkina Faso’s constitution, president of the Senate should take over after the president has resigned and an election should take place in 60 to 90 days. This provision, however, is irrelevant because the Senate has never been established. The President of the National Assembly, who could have legally led this transition is considered a ruling party insider and has lost every drop of legitimacy.

The opposition, customary leaders and foreign diplomats have been meeting with the army who seized power after Mr Compaoré resigned October 31st after days of massive anti-government protests. “The opposition is playing an important role in ongoing talks with the army on the transition” said Imad Mesdoua, a west Africa political analyst. It “will be the central player in the drafting of a road map to decide who will be the key managers in the transition, alongside the army.”

Mr Compaoré had been in power for 27 years, making him one of Africa’s longest serving leaders. After staging a military coup in 1987, he established political institutions, including a national assembly, allowed the formation of political parties and held elections. But his recent attempts to amend the constitution and run for a fifth term sparked massive protests that ended with demonstrators setting the parliament building on fire, looting other public and private property and forcing the president to flee to neighbouring Côte d’Ivoire.

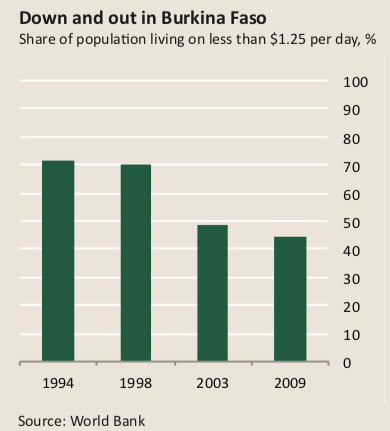

Opposition parties and other disgruntled citizens held large rallies in the last year against changing the presidential term limits. Growing social and economic dissatisfaction, particularly among young people, have fuelled these protests. Two-thirds of Burkina Faso’s 17m citizens were under 24 in 2010, according to UN figures, and Mr Campaoré was the only leader they ever knew. In 2009 46.7% of the population was living below the national poverty line, according to the latest World Bank figures. According to a government agency that monitors employment, 51% of the country’s youth between 15 and 29 were jobless in 2012. The protests were about the populace’s dissatisfaction with the attempts to change the constitution as much as their unhappiness with the widening gap between the wealthy ruling elite and the poor.

Mr Compaoré’s regime had already been weakened in January 2014 when several leaders from his Congress for Democracy and Progress (CDP) party defected and created a new opposition party, the People’s Movement for Progress (MPP, its initials in French).

The deserters left because they felt ignored, according to several key MPP members. “It’s the impossibility to act from within the party to carry through our ideals of democracy…that led us to leave reluctantly,” said Simon Compaoré (not related to the former president), one of the MPP’s founding members and the former CDP mayor of Ouagadougou, the capital. They also disagreed with the party’s management and its support for changing the presidential term limits.

Disaffection within Mr Compaoré’s party can be traced back to 2012, when the CDP overhauled its executive bureau. Influential party members—including former party president Roch Kaboré and former party vice-president Salif Diallo—were dropped in favour of a group of Mr Compaoré’s friends and relatives. Today Mr Kaboré is the MPP president and Mr Diallo his deputy.

The MPP’s formation initially raised much suspicion. Some opposition members, especially among the more radical parties,interpreted it as a ploy by Mr Compaoré to extend his power. Through hard work, and with time, the MPP activists have convinced the rest of the opposition that their defection from the CDP is genuine. The MPP now participates in joint opposition activities, such as marches and meetings, led by Zéphirin Diabré, leader of Parliament’s largest opposition party, the Union for Progress and Change (UPC).

“Attacks and manoeuvres against the MPP coming from the majority party confirm that they are perceived by the latter as one of the most serious adversaries among the opposition parties,” said Philippe Ouédraogo, a leader of the Party for Democracy and Socialism/Metba, another opposition party, before the uprising.

Before Mr Compaoré’s resignation, the opposition and civil society were united in their common struggle against the constitution’s revision. “Many people think, like me, that an opposition coalition including, or led by the MPP…has a serious chance to beat the CDP’s candidate in 2015, especially if Blaise Compaoré is not himself a candidate,” Mr Ouédraogo said in early October.

But without a common enemy, unity might be more difficult to achieve among parties with different visions and agendas. “The opposition is not as united as we think, there are deep divisions,” Mr Mesdoua said.

While the MPP defends social democracy, the UPC is resolutely liberal. The opposition also includes smaller, more radical parties, including some groups whose radical left-wing polices are inspired by Thomas Sankara, a revolutionary former president. “As discussions over leadership emerge, those divisions will worsen and egos will undoubtedly clash,” Mr Mesdoua added.

With Mr Compaoré out of the picture, and the CDP in disarray, political observers will closely monitor the shifts in Burkina Faso’s political parties as they vie for power. “If the MPP were to assume state power, would it be able to implement internal, economic and foreign policies truly different from what are currently in practice?” Mr Ouédraogo asked before Compaoré stepped down.

The MPP’s Simon Compaoré admits this is a legitimate question as many of its members were part of Mr Compaoré’s government for years. But it also means that this new party has the experience to ensure that “never again will someone try to modify the constitution to eternalise himself in power,” he said.

With Mr Compaoré gone, Burkina Faso’s future remains precarious. While the scheduled 2015 elections will now have to be brought forward, they have raised hope for a democratic “alternance”, or turnover. But until an interim government composed of civilians is installed, the army’s return to power is bringing back old demons. It remains to be seen if the current transition will lead to genuine democracy.