Is Julius Malema good for democracy?

“Today was a great day for democracy,” said Julius Malema. It was August 21, 2014 and the portly commander-in-chief of the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) was talking to a TV crew outside South Africa’s National Assembly, an “august chamber” whose decorum had just been shattered by Malema and his comrades, 24 young black men and women sporting red overalls and matching industrial hard hats.

South Africa’s parliament is a venerable institution, established in 1853. One does not wear boots and overalls in such a place. Nor does one cheek the presiding officer, refuse to shut up when ruled out of order or hammer one’s desk with a red miner’s helmet while chanting, “Pay back the money!”

As the entire world now knows, the money in question was the R246 million (about $22 million) used to upgrade the private rural residence of President Jacob Zuma in Nkandla, in KwaZulu-Natal. Public Protector Thuli Madonsela had ruled that some of this expenditure went beyond what was needed to protect the president and that he should refund a portion of the money spent.

At the start of question time on August 21, Democratic Alliance (DA) opposition leader Mmusi Maimane rose to inquire about Zuma’s position on another matter, only to receive an airy brush-off: the matter had been referred to the appropriate committee, Zuma said, and therefore, the question was not really a question. Maimane nodded and sat down again.

This was par for the course in an assembly where Zuma’s African National Congress (ANC) has been dominant for two decades: opposition parties demand accountability; ANC leaders ignore them.

Then Malema leapt to his feet to ask about Nkandla. Within seconds, the game had changed. “We want a date when we will get the money,” he thundered. “We are not going to leave this house before we get an answer!” Lesser fighters leapt up behind him, shouting “Where’s the money?” Other members of parliament (MPs) rose up too, and pandemonium ensued.

“I will throw you out if you don’t listen!” shouted the speaker, Baleka Mbete. Struggling to make herself heard above the noise, she ordered the sergeant-at-arms to evict Malema’s rabble. But they stood their ground, jeering, hammering on their desks and chanting insults. In the end, Mbete declared an adjournment and called the riot police, who seemed unsure as to what law had been broken, if any. According to Malema, there was also an attempt by ANC staff “to beat us up but we barked at them and they disappeared because they are cowards”. He and his red squad remained in their seats until the uproar died down and then left of their own volition.

The man at the centre of this electrifying piece of guerrilla theatre was born into desperate poverty in 1981 and raised by his grandmother, a domestic servant in the northern town of Polokwane. He joined the ANC at age nine, and became president of the ANC Youth League 18 years later. In a country where nearly half the population is under 25, the youth league has always been a springboard to greater things for ambitious young men. Malema was clearly one of those, an aggressive hustler who constantly drew attention to himself by staking out positions to the left of his party’s leadership. Nationalise the mines, he declared. Seize white-owned farmland without compensation. Fulfil the promise of the Freedom Charter by taking over banks and monopoly industries.

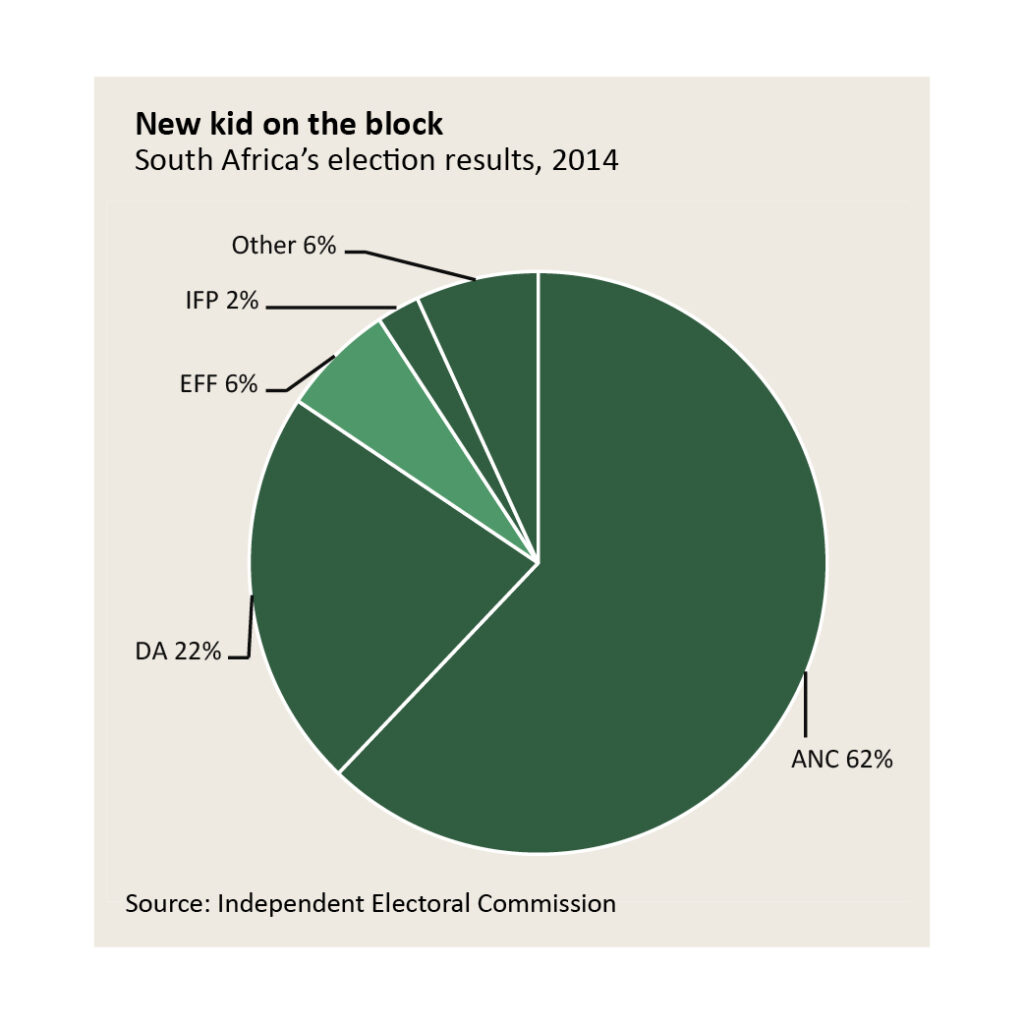

By 2011 Malema had become such a threat to his elders that they booted him out. Political obituaries were written but Malema secured funding from anonymous kingmakers. He came back in 2013 as the founder of the Economic Freedom Fighters, a political party billed as an “army of the poor”. Despite a late start, the EFF won 6.35% of the vote in this year’s general election – enough to send 25 fighters to mau-mau the National Assembly.

After the “Battle of Question Time”, Malema declared that he had made history. “There has never been opposition since 1994,” he said, referring to the date Nelson Mandela became president. “Today was the first time the ANC saw it.”

Well, not really. From its first day in power, the ANC has faced opposition from mature politicians skilled at duelling with points of order, committee manoeuvres and procedural technicalities. These rites made sense in Britain, from whence they came. But in South Africa, the ANC’s unassailable majority rendered them largely pointless. Consistently returned to power with at least 60% of the vote, the ruling party was always able to control parliamentary committees, outvote challenges and shield leaders like Zuma from hostile scrutiny.

This idyll has now ended, according to Malema. “(The ANC) has met a real match,” he said. “We are here to make them run for their money.”

This was vintage Malema. “JuJu”, as he is known to friends, is a charismatic populist in the tradition of Juan Peron of Argentina, Hugo Chávez of Venezuela and perhaps Idi Amin of Uganda. He is short and heavy, with a shaven head and bulldog jowls. When he says, “We are not going to be bullied by the ANC,” you believe him. And when he adds, “If they are looking for a fight in the streets, we are ready,” you believe that too.

But is he really the champion of democracy he claims to be?

There is no doubt that millions of South Africans were thrilled to see someone standing up to government and demanding an explanation for at least one of the myriad corruption scandals currently facing us. Equally pleasing was the spectacle of smug ANC leaders growing incandescent with rage as they assailed Malema’s followers as “hooligans” beset by “infantile disorders”.

The result was extraordinarily enthusiastic press coverage. News24’s Georgina Guedes gushed that Malema was doing a “brilliant” job. Eusebius McKaiser of The Star found him “very impressive”. Gareth van Onselen of Business Day compared Malema to the DA’s parliamentary leader, and found Maimane desperately lacking: “Does [Maimane] set the oppositional agenda? Is he the most forceful leader, the most charismatic? Do his words command attention and his actions necessitate change? The answer to all these questions seems to be a resounding ‘no’…. Maimane is the glow of a dying ember; Malema is a blowtorch.”

In short: only Malema is tough enough to stand up to and defeat the mighty ANC.

Maybe so. But what then? Malema is quick to condemn corruption these days, but during his Youth League heyday, he was pork-barrelling with the best of them, miraculously acquiring houses, cars and a farm on his modest Youth League stipend. (South Africa’s tax authorities have confiscated most of these assets; and Malema has yet to stand trial for the allegedly rigged tenders that financed them.)

Malema is also quick to present himself as a staunch constitutionalist. “The rot has eaten away the government of this country,” he said earlier this year. “The only thing left for us is the constitution. Let us protect it with everything we have.”

Another fine sentiment, but does he really believe it?

Malema’s very first appearance in South African newspapers involved a student protest in downtown Johannesburg that degenerated into looting and violence. According to his biographer Fiona Forde, his campaign for the ANC Youth League presidency relied heavily on intimidation. Back in 2007, when he and Jacob Zuma were still allies, he famously declared himself willing to kill on behalf of the president. There is implied violence in his support for Zimbabwean tyrant Robert Mugabe, and in his depiction of whites as “thieves who should be treated as such”. In September 2014 he was at it again, threatening to take up arms if the ANC used violence to block his rise to power.

“This man is a democrat? I certainly hope so,” says Anthea Jeffery. “But I wonder. Democrats usually argue with their opponents, rather than threaten to kill them.”

Jeffery is head of policy research at the Institute of Race Relations, a think-tank. Like many South Africans, she was hugely amused by Malema’s mau-mau campaign, which has turned “pay back the money!” into a catchphrase gleefully deployed against all manner of dubious characters by South Africa’s stand-up comedians. On the other hand, she feels the media has overstated Malema’s significance.

“The wily old guard of the ANC saw Julius coming a mile off and began stepping up their own radical rhetoric,” she says. “They saw that Julius was trying to challenge from the left, but they had their own leftist prescriptions to counter this. Unlike Malema, they also had the power to start translating these ideas into law.”

In a new book titled BEE: Helping or Hurting?, Jeffery tracks this process back to 2011, when the ANC first suspended Malema. She shows how it gained traction at the ANC’s 2012 national conference in Mangaung, where Zuma famously announced that the second phase of the South African revolution was about to begin. The rest of the media reported his speech and fell asleep. Jeffery, almost uniquely, kept her eye on the ball, tracking radical policy proposals as they moved into draft bills and, in most cases, into measures since adopted by Parliament, if not yet signed into law by the president.

According to Jefffery, it is naïve to believe that the ANC remains committed to the National Development Plan (NDP), a programme whose moderate precepts were warmly applauded by the World Bank, the IMF and foreign investors. She believes the party has quietly abandoned the NDP and is poised to move rapidly leftward, a move that could render Malema irrelevant.

Photo: Marco Longari / AFP

Since Jeffery’s analysis is not exactly conventional wisdom, sceptics might wish to suspend judgement until they have read her dissection of the 2013 Protection of Investment Bill, which strips foreign investors of the right to appeal to international arbitrators if the South African government seizes their assets. Or the 2013 Mining Amendment Bill, which allows the government to take control of oil or gas fields developed by private companies and pay whatever compensation it pleases. Or a new land reform proposal that requires farm owners to give up 50% of their land, effectively without compensation.

Also of interest is the draft 2013 Expropriation Bill, which empowers thousands of officials at all three tiers of government to expropriate property of virtually any kind. This should be read alongside the aforementioned Investment Bill, which seeks to allow the government to do so without compensation – provided that they are acting as “custodians” for the previously disadvantaged masses.

This would in theory enable the state to confiscate your business as “custodian” and then invite blacks to apply to run it without paying you anything. The process could be expedited if the property on which your business stands is subject to a land claim. So it is perhaps not coincidental that the ANC has recently re-opened the land claims process and expects to receive close to 400,000 new claims over the next five years.

Lay these ANC laws alongside the EFF’s manifesto and it becomes clear that any ideological differences between the parties are less significant than the rivalry between their respective leaders. This clash produces showers of sparks, but does the outcome really matter? If Malema wins, South Africa will become a socialist people’s republic, devoid of economic growth and foreign investment. If Zuma prevails, ditto. If the nation is to avoid this fate, we have to look for salvation elsewhere.

Since June 2014, when the EFF made their parliamentary debut, the Democratic Alliance has taken a public battering simply for being itself – a sober, hardworking party staffed by MPs and researchers whose heads are perpetually buried in dull position papers and whose leader, Maimane, is a politician in the suave Barack Obama vein; a thoroughbred alongside Malema’s dray horse. It irked me to see him belittled simply because his manners are better than Malema’s. Would we really prefer a blustering charlatan?

At the last election, the DA won the support of about 23% of the electorate. With majority support in the white, coloured and Indian communities and three-quarters of a million black voters, the DA is the only truly multiracial party in South Africa. With 89 members of Parliament, it is also the only party whose embrace of rule of law and at least relatively free enterprise seems to offer an alternative to policies presently dragging South Africa into deepening crisis.

This article first appeared in Africa in Fact, Issue #29, December 2014 – January 2015