Burkina Faso: locals vs. newcomers

Tensions between old and new land laws fuel conflict in Burkina Faso

Land disputes are causing strife throughout Burkina Faso. From the fertile south-west, across the central Mossi plateau and up to the eastern region bordering Niger, land feuds tear families apart and set clans against each other in this landlocked west African country.

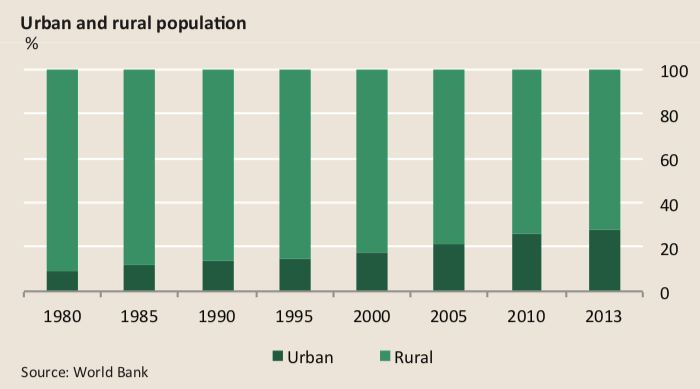

The conflicts arise because of rapid population growth (the average Burkinabe woman bears 5.7 children during her lifetime, according to 2012 World Bank figures), internal and cross-border migration, and soil degradation, all of which put pressure on the limited arable land.

Clarifying land ownership laws would go a long way to resolving these conflicts. At the heart of the tension is the uneasy co-existence of customary and modern law, especially in the countryside. Burkina Faso has a largely rural population: only 27% of the country’s 17.4m people living in cities, according to 2012 World Bank figures.

Rules dating back to the ancient era of the Mossi kingdom and other pre-colonial political systems remain powerful across Burkina Faso. According to most traditional practices, land belongs to the leaders of the country’s original inhabitants, the “land chiefs”, who may lend it to non-indigenous people.

State law, however, does not recognise these customary practices. According to modern Burkinabe legislation, land is either state property or privately owned. Although state law does not recognise customary law, traditional practices often prevail as weak government institutions have failed to enforce state law across the country, especially in rural areas, leaving ample space to traditional customs.

The Burkinabe Agrarian and Land Reorganisation law (RAF), adopted in 1984 under the Marxist president, Thomas Sankara, made the state the default owner of Burkina Faso’s land. The state could give operating rights to mayors, governors and other modern local authorities or to private individuals as it wished.

During the 1990s the government revised the RAF and reintroduced the concept of private property. These revisions were a reaction to the migrants coming from other parts of the country or the sub-region, including the mass return of former Burkinabe emigrants in Côte d’Ivoire fleeing the civil war and targeted violence. The newcomers began settling on lands without abiding by traditional customs. They argued that “land belonged to the state, therefore it belonged to everyone,” according to Djibril Traoré, an agronomist who authored a UN-sponsored study on land reform in 1999.

These conflicting visions of land ownership have created grey areas with many toxic repercussions.

Intergenerational tensions between youth under 35 and their elders are a common consequence of these shadowy areas, according to Germain Nama, a well-known journalist and commentator in Burkina Faso. “Some youth sell land without consulting the elders, which often fosters tensions,” Mr Nama said. “This type of conflict is very frequent, because our youth is thirsty for money.”

Modern commercial transactions, such as leasing and selling land, are becoming more and more popular among rural Burkinabe. This is especially true in the south-west region, where the proliferation of gold mining and agribusiness (in cotton, cereals and cattle) has inducedowners of small plots to sell their land. A few powerful economic operators, some with political connections, now monopolise huge swathes of land.

For example, in the village of Neboun in the fertile south-western Sissili province,most of the land is divided into dozens of large agricultural complexes spread over hundreds of hectares,leaving local inhabitants who sold their land without income and property to leave to their children.

The grey areas also lead to conflict between indigenous and non-indigenous people. A chief’s descendants can reclaim land from the descendants of migrants, according to customary law. The application of this traditional law sometimes turns violent. For example, in Yirini, a village in the east, a newly appointed chief demanded that an opponent’s supporters leave the land they had been occupying for several years. This led to the killing of six people in June 2013 after one family started working the land, angering the other side who attacked them before the police could intervene.

Mistrust of the state’s judicial system adds fuel to the fire. The courts were perceived as the third most corrupt governmental service in 2011 and 2012, according to the yearly reports produced by the National Anti-Corruption Network, a civil society system based in Ouagadougou, the capital. The judiciary’s apparent lack of independence, easily swayed by political and financial influences, explains the poor ranking, according to the report.

In addition, the state too often relies on customary leaders to mediate, even when some “have lost credibility due to their implication in politics,” according to Boureima Nabaloum, a director-general in the youth ministry.

When conflicts over land arise and state courts or customary dispute resolution mechanisms fail, people resort to violence, personal revenge or collective punishment. In Yirini, for example, the state courtsmade a ruling two years before the deadly violence, but it was never carried out. This failure led both sides to take matters into their own hands.

The government is trying to clear the confusion. A six-month-long consultation of customary chiefs, members of local cooperatives, women’s associations, business people and government officials culminated in a national workshop involving 500 people in May 2007. This prompted the legislature to adopt a law in 2009 that established procedures for providing ownership certificates to anyone who files a claim with the local authority. If the claim is opposed an enquiry is made to determine who rightfully owns the land.

Implementation again is a problem: five years after the law was adopted, only 17 towns and communes, or groups of villages, have applied the law out of the country’s 351 communes. While the government added 30 new communes to its targeted areas last June, it is still a long way from achieving national implementation.

Another weakness is that the new law ignores the status of migrants, even those who have been occupying a plot of land for years or generations. Considering the violent controversies that have arisen over this, legislators need to address this omission urgently.

The 2009 law was an important step in the right direction. Fixing its limitations in content and application will require more participatory decision-making and more transparency. The government also needs to strengthen the court system and other dispute resolution mechanisms so that they are trustworthy and communities will solicit them when a disagreement occurs.

Some recent initiatives are encouraging. About 700 magistrates and justice auxiliary agents took part in a training programme in June 2013, run by the justice ministry, aimed at promoting a common understanding of the country’s land management law. Initiatives like this should be repeated in the future and extended to local and customary authorities to consolidate the ground gained by the recent reforms.

Once this is accomplished, the state can start tackling other land-related issues: migration, population growth and soil degradation.