Higher education and urbanisation

Universities play a vital role in cities, creating infrastructure, boosting business and developing understanding

The role universities play in Africa’s cities is too often ignored, forgotten or viewed as irrelevant. Institutions of higher education are rarely considered part of an urban community. Instead they are viewed as elite spaces or “ivory towers” that are far removed from activities in their immediate metropolitan vicinity.

But as economic development continues apace across the African continent, universities and the higher education sector are in a good position to address the opportunities and challenges that urban expansion brings, particularly in the physical and social development of the continent’s cities.

Numerous studies in North America and Europe have documented the role universities play in urbanisation. A particularly noteworthy case is Columbia University’s intervention in Harlem, New York, where the institution sought to reinvigorate an eco- nomically and socially depressed area through large-scale infrastructure development in 2004.

But very few reports have examined this relationship in Africa. This is surprising because African universities can be crucial partners as cities expand and transform. They can contribute to urban renewal and growth through infrastructure development, the stable employment of large numbers of educated people and by generating income for local business. They are centres for innovation and creativity and can assist in finding solutions to a city’s economic and social problems.

To function properly, universities require myriad forms of infrastructure, from office space to laboratories to lecture halls to libraries to housing for students and staff. Often located in city centres, universities own significant and valuable real estate that can drive urban renewal or development. For example, the University of the Witwatersrand (often referred to as Wits) in Johannesburg is partnering with the city and private enterprise to redevelop buildings for student and staff accommodation in Braamfontein, a downtown district. By creating housing in this area, the university and its private and public sector partners are contributing to the revitalisation of a city neighbourhood that has been depressed for over 20 years. This will open up opportunities for further economic development as small and medium enter- prises set up shop to cater to the university staff and students living and working in this area.

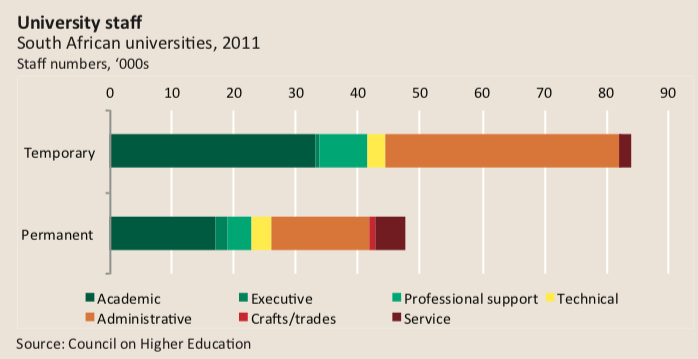

Universities are major employers in cities and this generates a secure local tax and consumer base. South African universities employed about 50,000 permanent and temporary faculty members in 2011, according to the Council on Higher Education (CHE), an independent South African statutory body that advises the higher education minister. The overall number of staff employed was much higher however, adding up to about 130,000 because it includes a wide range of administrative, technical and other support staff.

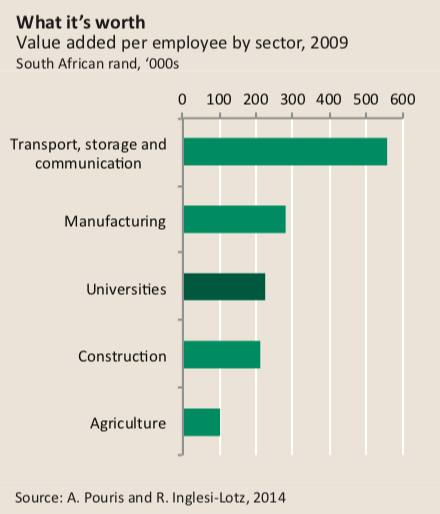

These workers, faculty members and students need and boost local businesses. Universities require significant support—from stationary suppliers to auditing services to raw materials to insurers, bankers and lawyers. University personnel pay for these goods and services and thus provide a consistent income and consumer base for businesses within a city.

UK universities contributed $5.7 billion to the British economy in 2011-12, ac- cording to the Higher Education Funding Council for England, the primary government funding agency for universities. If universities in Africa quantified what they bring to local economies, they would have an improved understanding of their local and nation- al impact and influence.

Richard Florida, a well-known American urban economist, wrote how cities can be seen as “cauldrons of diversity and difference and as fonts for creativity and innovation” in a March 2003 article in City & Community, the journal of the American Sociological Association. Mr Florida argues that diversity and creativity are fundamental drivers of innovation and economic growth. Urban universities are essential to attracting, fostering and training distinct and inventive individuals. Their vibrant teaching and research environment is crucial to achieving a creative and innovative city.

Universities are also vital to understanding Africa’s challenging urbanisation issues. Migration into metropolises raises population density, which can exacerbate inequality and poverty. This can turn cities into centres of social conflict, particularly between migrant groups competing for shelter, formal employment and access to basic services. Xenophobia can emerge when foreign workers seek a better life in the city.

Urban areas are also places of hope and excitement. Much of the “Africa rising” narrative can be credited to the continent’s vibrant cities, where infrastructure development, job creation and wealth generation are leading to investment in remarkable architecture, public art and innovative entrepreneurial endeavours.

Universities are natural settings to consider, debate and understand urbanisation’s challenges and opportunities. Nevertheless very few higher education institutions in Africa have urban planning research departments or academic programmes. Uganda’s Makerere University and South Africa’s University of Cape Town (UCT), University of the Free State and Wits University are notable exceptions.

Research at UCT’s African Centre for Cities is shedding light on how to address pressing urbanisation problems such as food security, pollution and climate change. Professors Vanessa Watson and Babatunde Agbola recently highlighted how urban planning students at Makerere University are developing city plans that include informal settlements. At Wits University, academics have partnered with the city of Johannesburg to address informal trading, which is largely driven by foreign migrant workers.

These universities are assisting policymakers in finding solutions to the social, political and economic problems facing African cities. As urban development spreads across the continent, more institutions of higher learning will need to step up and get involved in this issue.