Republic of Congo’s puppet master

A master rule-breaker is preparing to change the rules again

While elections in the Republic of Congo are a year away, Brazzaville, its riverside capital, is awash with rumours that the president will amend the constitution, again, to remain in power. Denis Sassou-Nguesso, 72, has ruled over the oil-rich state for nearly 35 years, against a backdrop of coups, civil wars and repeated constitutional revisions. He first came to power after a military takeover in 1979 and ruled until 1992, when he lost a presidential election to Pascal Lissouba in the nation’s first multi-party elections. He took the reins again in 1997 at the end of a period of bloody civil war. He won two disputed elections in 2002 and 2009. Often referred to as Congo-Brazzaville (to distinguish it from neighbouring Democratic Republic of Congo), this nation’s first constitution was replaced by a second one in 2002, which, ironically, Mr Sassou- Nguesso himself helped to draft.

Article 57 limits consecutive presidential terms to two; and Article 58 forbids candidates over the age of 70 from running. The president should be excluded on both counts. While Mr Sassou-Nguesso has made no public statement regarding his potential candidacy, opposition leaders and other observers are convinced that the president will try to change the constitution to run again. Few forget his late 1970s campaign slogan Kaka Nguesso (“Nguesso one more time” in the Lingala language). The president is consulting constitutional experts to modify “the constitution to his advantage”, said Mathias Dzon, president of the opposition Patriotic Union for National Revival. This information is “not a secret”, he added. The ruling Congolese Labour Party (PCT) has only encouraged these perceptions. In December 2014 the PCT’s steering committee approved plans to modify Articles 57 and 58, according to several newspaper reports. But Article 185 remains a major obstacle: it prohibits revising the restrictions on presidential terms.

The only way to remove the term limits is to scrap the constitution entirely. The country’s first postcolonial constitution was adopted in 1963. After 29 years of one-party rule, the constitution adopted in 1992 paved the way for multi-party elections. But Mr Sassou-Nguesso abolished it when he overthrew Mr Lissouba and replaced it with a transitional charter in October 1997. A civil war, fought between partisans of the two men, continued on and off until December 1999, when Mr Sassou-Nguesso, with the help of the Angolan army, finally won a decisive victory. He led a transitional regime until elections in 2002, when a new constitution was adopted. But even with these limits, the 2002 constitution still gives the president imperial powers. The president is both chief of state and head of government. He appoints ministers, councillors and directors-general. In addition, he is commander-in-chief of the army and president of the superior council of magistrates.

“In Congo, the president does everything,” said Vivien Manangou, a law professor at the University of La Rochelle in France. The 2002 constitution was drafted to restore the state’s authority, weakened by years of civil war. By extending powers to the executive, it sought to break away from the 1992 constitution’s French semi-presidential system, in which parliament played a counterbalancing role. But what Mr Manangou qualifies as a “paternalistic” constitution nevertheless had one important caveat: Article 185. Those in favour of removing Article 185 argue that the constitution has done its job. “The historical role played by the [2002 constitution] has ended,” said Thierry Moungalla, minister of telecommunications. “The constitution is not the bible. [It] was drafted by men in a specific political, social and economic context. What has been drafted by men at that period in time, influenced by major political circumstances, can be modified by these same men.”

If Mr Sassou-Nguesso succeeds in scrapping the old constitution and drafting a new one, it will not be the first time he has changed the rules to suit his needs. He may need to remain in power to avoid prosecution and protect his patronage networks. For instance, he could face charges for his involvement in the murder of Marien Ngouabi, Congo’s president who was assassinated in 1977. Mr Sassou-Nguesso was defence minister and head of intelligence at the time and became president two years later. In 2013 several independent newspapers dared to link Mr Sassou-Nguesso to Mr Ngouabi’s murder. The national agency responsible for regulating the media suspended the news outlets for inciting “violence, defamation and dishonouring certain high authorities of the state”. The president could also face charges of crimes against humanity.

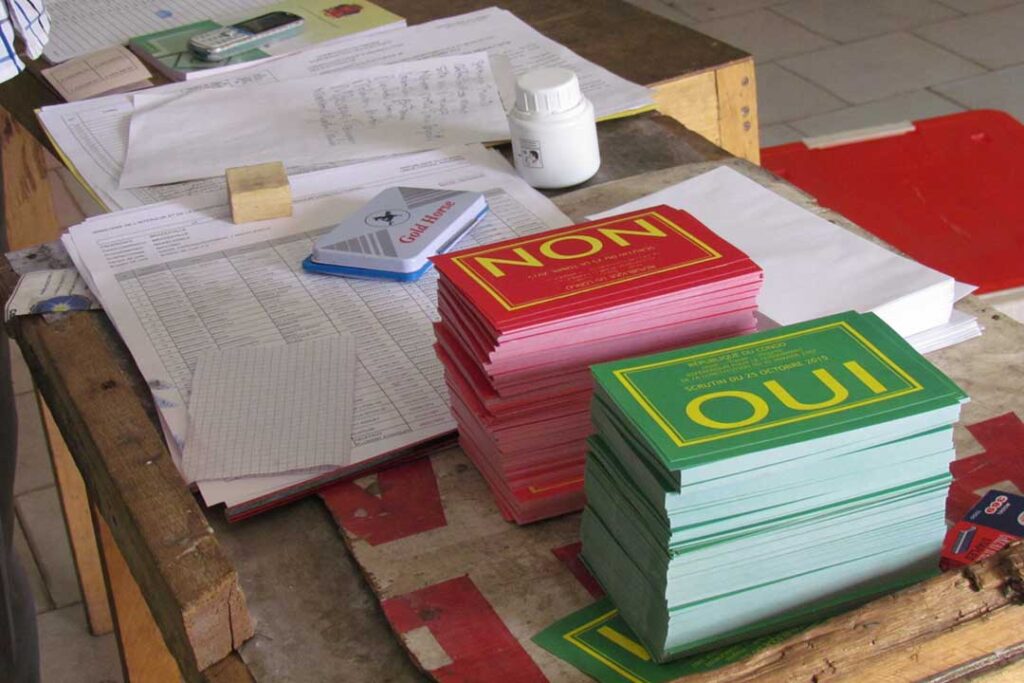

Commentators have linked him to various political crimes, not least the infamous Brazzaville Beach incident in May 1999 in which over 300 Congolese refugees, returning from exile at the Kinshasa port, were allegedly tortured and murdered. The president’s family, close friends and his Mbochi ethnic group dominate the media, state business and key government agencies. General Jean-François Ndenge, a close friend, heads the national police force. The president’s nephew, Jean-Dominique Okemba, is in charge of the national security council. If there is a constitutional referendum, it will most likely take place before presidential elections scheduled for July 2016. Aside from the legal hurdle, Mr Sassou-Nguesso faces an increasingly mobilised and vocal opposition. In the last election in 2009, opposition candidates called for a boycott. They released a statement on election day asserting that turnout was only 10%, a claim disputed by the government.

The PCT’s support for an extension of the president’s rule is creating the ingredients of a “very grave” crisis, Mr Dzon said. The president’s “unpopularity is established,” he added. Yet still “he wants to move mountains…to offer himself an additional term he is not allowed to have. The Congolese people are not going to let that happen.”