The introduction of the 2010 Constitution in Kenya was monumental, particularly for the decentralisation of civic participation. This framework was a significant step in further cultivating civic engagement in Kenya. This article examines the factors that strengthen and impede civic engagement in Kenya and finds that although the deepened institutionalisation of governance and democracy strengthens civic participation, it does not sustain it. It is therefore worth identifying factors that contribute to the gap between the institutionalisation of governance, democracy, and civic engagement, as this can provide insight into how to narrow this gap.

Historically, civic engagement has played a central role in African politics. Before the third wave of democracy in the early 1990s, civic engagement included inkundla/lekgotla meetings, hometown associations, and ethnic welfare associations. According to CIVICUS’s 2022 Civic Society Index report, civic space is under threat globally, and it is civil society that plays a critical role in holding those responsible to account. CIVICUS also noted that in eight African countries in 2008–2011, civic engagement in Africa was relatively high compared to other regions. However, as of 2023, CIVICUS assessed 27 African countries as repressed, 14 were “obstructed”, three “narrow” and two “open”, indicative of a repressed civic space in the region.

To attain and maintain democratic health requires a joint effort by the state and its citizens. Citizen engagement can take place in campaigning or advocating for shared goals, engaging with governments, holding them accountable, and making demands of them. It can also take place through paid employment in non-governmental advocacy. More importantly, civic engagement takes place in a voluntary capacity. This article is interested in understanding the nature of the latter engagement in the Kenyan context.

Civic engagement is determined by many factors, including but not limited to the type of political system, the effectiveness of local government, and the country’s history, which shapes its social, political, and ideological framework. For example, Sudan’s political ideology is largely undermined by ethnic politics, which took shape during its colonial experience. Decades later, ethnic divisions and ethnic-based politics remain an underlying feature in Sudan. In South Africa, political ideology is shaped by its apartheid experiences of inequality. In Tunisia, the 2011 Arab Spring has and continues to shape the nature of governance and political system; in Rwanda, the 1994 genocide has significantly shaped the country’s post-genocide political ideology. Similarly, Kenya’s political ideology has been shaped by inequalities and by post-colonial experiences that contributed to the 2007–2008 post-election violence.

Like many other African countries, Kenya’s current democratic landscape has been shaped by its unique colonial experience. The colonial administration concentrated on developing certain regions and excluded others; this further entrenched ethnic inequalities. Post-independence, ethnic fractionalisation was not addressed but has been weaponised for political gain. Additionally, because inequality has ethnic undertones this also fuels ethnically polarised national politics and, therefore, public participation in politics and the democratic process.

However, the Kenyan government has made great strides in strengthening and consolidating civic engagement. This includes transitioning from a single party to a multiparty system, and the adoption of a new constitution in 2010 that makes provision for public participation. This new constitution was monumental as it introduced a new system of decentralised governance. This new system restructured the government system by establishing one national government and 47 county governments. The new constitution also addressed the issue of inequality and exclusion, where marginalised counties could now have access to grants to address these inequalities. Public participation is further institutionalised through the County Governments Act (2012), the Public Finance Management Act (2012), and the Intergovernmental Relations Act (2012).

How has the institutionalisation of decentralised governance influenced civic engagement in Kenya? Who is upholding civic engagement in Kenya and what lessons can other African countries learn from the Kenyan experience?

Pan-African research network Afrobarometer measures civic participation by accounting for different typologies, which include attending community meetings; contacting political and civil society leaders or government; joining forces with others to raise an issue; and involvement in a community group or voluntary association. Compared to other African countries, participation across these measures is relatively high but on the decline in Kenya.

According to the Afrobarometer, on average, attending community meetings is the most common form of civic engagement (58% ) in Africa. However, there is great variation between countries: 89% of Madagascans attend community meetings, 82% in Tanzania, compared to only 12% in Tunisia. About 24% of Africans say that they are either leaders or active members of voluntary associations or community groups. The proportion is the highest in the Gambia (54%), Liberia (50%) followed by Kenya (46%) and is the lowest in Morocco, Mauritius, and Madagascar (9%), and Tunisia (6%). Worth noting is that, except for Mauritius, according to Freedom House, all the lower-ranking countries are classified as partly free.

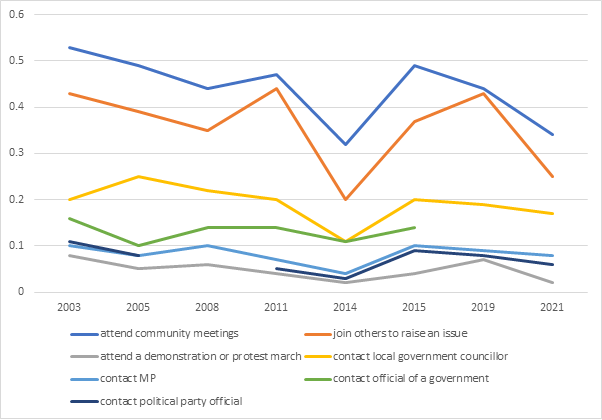

It is interesting to note that changes in Kenya’s constitutional reform have been met with divergent changes in civic participation. Figure 1 depicts a time trend of civic participation in Kenya.

Figure 1 | Civic engagement in Kenya

Kenya has adopted various mechanisms and platforms to promote citizen participation. In addition to the mentioned Acts, the Kenyan government has made use of public forums such as newspapers, local community vernacular radio stations, announcements on national websites, and social media platforms to encourage citizens to attend public forums. So, why is this not translating to sustained civic participation?

As Figure 1 indicates, in Kenya civic engagement – across all indicators – was the highest in 2003. Engagement was particularly high for the attendance of community meetings (53% ) and joining others to raise an issue (43%) while it was lowest for the attendance of a demonstration or protest march (8%). Between 2003 and 2008 there was a decrease in civic engagement across all indicators – except for contact with a local government councillor. This decline coincides with the post-election violence of 2007-2008, which was fuelled by ethnic polarisation.

As noted earlier, the 2010 Constitution significantly altered the structure of government with the executive’s powers reduced. Additionally, provisions were made for the reallocation of human and financial resources, as well as political power to help address the imbalances of the past. More importantly, the Constitution provided an avenue for the marginalised to address their grievances. Unsurprisingly, in 2011 there was a significant increase in civic participation.

The challenge for Kenya is in maintaining citizen participation. Civic participation reached an all-time low in 2014, with a sharp decrease across all indicators. This general decline is the result of various factors, the most potent being a weakened civil society that is argued to have become more reactive and some of its strong members absorbed by the government. In addition, the former Kenyatta government made great efforts to suppress and restrict civil society activities, including violence and police action against demonstrators as well as imposing limitations on freedom of speech and assembly through legislative initiatives.

But Makueni County is a success story worth noting. Makueni County’s public participation model enables citizens to engage in local governance decision-making and processes. For example, citizens are allowed to identify their development priorities and are involved in the planning, prioritisation and setting of budgets and expenditures for identified projects. The county also consults with the public to make decisions and to obtain their feedback on alternatives. The public is also kept informed and involved to ensure that their concerns are considered throughout the decision-making process. This model simultaneously captures indigenous practices and formal democratic governance practices. In essence, it narrows the gap between institutional performance and individual experiences and expertise.

The Makueni example illustrates why it is necessary to understand, cultivate and invest in civic engagement. In the case of Kenya as a whole, it has made great strides in institutionalising and decentralising power and governance. Although there are impediments and gaps between the institutionalisation of civic engagement and actual civic participation, Makueni offers a model to close this gap.

Kenya has established its own, homegrown model that can be used as a reference point for other African countries. The health, longevity and stability of democracy is highly dependent on civic participation as citizens are the ones who uphold and defend democracy.

MmabathoMongaeis a Data Analyst within the Governance Insights & AnalystProgramme. She is a PhD candidate in International Relations at the University of the Witwatersrand, and her thesis research focuses on how governance quality influences popular support for and satisfaction with democracy in Africa. While completing her PhD, Mmabatho worked as Sessional lecturer in the International Relations Department at the University of the Witwatersrand and as a research fellow at the Centre for Africa-China Studies (CACS) at the University of Johannesburg. Her research interests include democracy, governance, Africa’s political economy, and quantitative social analysis. Mmabatho has published research for Routledge, EISA, and The Thinker.