Gambia’s Group of Six

These half-dozen opposition parties refuse to participate in another sham election

Gambia’s President Yahya Jammeh wants the world to think he is a democrat. Two years after seizing power as a 29-year-old officer in a 1994 coup, he held elections. He won. Since then he has won three more: in 2001, 2006 and 2011, all widely criticised.

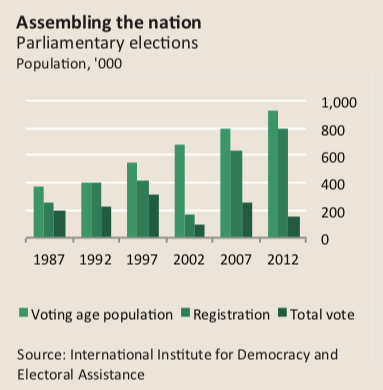

But this democratic façade is crumbling. Six of the main opposition parties in Gambia have vowed to boycott the next presidential election, scheduled forNovember 2016, after the head of the Independent Electoral Commission (IEC) rejected their calls for electoral reform in 2012. So far they have not participated in the March 2012 parliamentary election and the April 2013 local election. Only one opposition party has contested the ruling Alliance for Patriotic Re-orientation and Construction (APRC) party in these two elections.

“There is no gain contesting an election that will not be free and fair,” said Ousainou Darboe, leader of the United Democratic Party (UDP), which received 17% of the vote in the 2011 poll, more than any other opposition party.

Popularly known as the “Group of Six”, these opposition parties had asked the IEC to end Gambia’s “first past the post” electoral system, which gives victory to a candidate with a simple majority. Instead, they want a “second-round”system, where a candidate who wins less than 50% faces a run-off election. First past the postfavours a powerful incumbent since it spares him the threat of facing a coalition uniting behind one candidate in the second round.

The six parties have also called for an end to the arrest and intimidation of their supporters. Twelve members of the opposition UDP’s youth wing were arrested in February 2014 for “unlawful assembly” and acquitted in court a month later. The coalition also wants the ruling party, Alliance for Patriotic Restoration and Construction (APRC), to practice neutrality in the hiring of civil service employees, especially in the police and armed forces.

They also demand transparency in the operations of parastatals such as the ports authority and the electricity company, which the six opposition parties accuse of bankrolling the APRC.

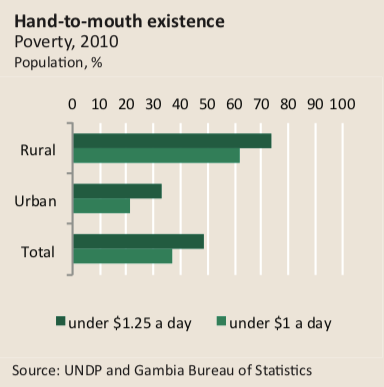

Gambia is one of the poorest countries in the world. More than 60% of Gambia’s 1.8m people live below the poverty line of $1.25 a day, according to the World Bank. Yet party leaders—both opposition and the ruling-aligned—drive flashy cars, own properties in expensive neighbourhoods in Banjul, the capital, and send their children to universities abroad.

Despite the ongoing electoral boycott, Gambia’s opposition parties try to make their voices heard in a media that often practices self-censorship because of the country’s “intolerant and unpredictable” government, according to Reporters without Borders. Journalists convicted of libel or sedition face jail terms.

The government shut theStandard newspaper and Taranga FM radio station from September 2012 to January 2014 following the publication and broadcasting of articles that criticised the government’s execution of nine prisoners in August 2012.

A 2013 law introduced a 15-year jail term and a fine of about $100,000 for anyone who uses the internet to “make derogatory statements [or] incite dissatisfaction” against the government or public officials. “This has led to self-censorship among journalists,” said the Gambia Human Rights Network, an international grouping of human rights organisations, in a 2014 report.

In addition to electoral and media constraints, funding is a perennial problem for opposition parties. Party leaders mostly fund political activities from their own pockets. In July 2013, the leader of the National Democratic Action Movement (NDAM) asked Gambia’s diaspora to send money to support party activities at home.

The Group of Six’s joint boycott is a sign that the opposition may be uniting, but they have tried this before, unsuccessfully. While one opposition party has failed to join the boycott, two other parties have not joined the coalition but have not participated in any elections either.A coalition of opposition parties in 2005 split shortly before the 2006 presidential elections when party leaders failed to agree on who should lead the alliance. This might happen again.

The current coalition is seeking to level the playing field and to mount a truly united front. If this cannot be achieved, a united boycott would be the best option. It might draw regional and world attention to the façade that is Gambia’s democracy. It could inspire the African Union and other international organisation to pressure Mr Jammeh into opening the democratic process.