Decentralised systems of governments in sub-Saharan Africa have been hailed as transformative because of their key role in the delivery of public services and contribution to higher growth. But these roles are delivered against a backdrop of multiple challenges, including limited resources, weak institutional capacity and accounting and accountability mechanisms.

Administrative inefficiency, gaps in policy, weak laws, and collusion between unscrupulous local government officers and cash collection firms and leakages have conspired to deny decentralised units the much-needed revenue that would offer relief for myriad financial challenges.

Indeed, the fundamental problem confronting most local governments, especially in developing countries, is the widening gap between the availability of financial resources and spending needs. There are concerns that local governments over-depend on central government transfers, with less revenue derived from property taxation and service charges.

In a number of African countries, although decentralisation has empowered many regions that would otherwise lag behind, sub-national governments are struggling to establish their Own Source Revenue (OSR) generation.

For example, in Kenya and Nigeria where devolution, the strongest form of decentralisation that offers local governments full discretion and broad policy guidelines under which to implement programmes, is being practised, devolved units have struggled to finance their projects and activities, with dismal own-source revenue collection.

In Tanzania, there were concerns by some financial management property experts that the national government was usurping lucrative local government revenue sources, including property rates, a levy on billboards and service levies. Similar stories are found across Africa. In some cases, the transfers to local governments are largely earmarked by central government to provide specific goods and services. At the same time, transfers from central government are significantly low.

There are no easy or quick reforms to increase OSR at local government level. However, efforts to increase sub-national government revenue must start with the creation of an enabling environment – decentralisation policies and legislation to support the process.

In Nigeria, for example, there have been calls to strengthen laws that establish and empower local governments – the third tier of government – through a review of legislation, by none other than the former president of Nigeria, Goodluck Jonathan.

In April 2021, addressing the Nigeria Union of Local Government Employees, who had paid him a courtesy call to seek support against a Bill that was seeking to delist local governments from the constitution, Jonathan implored the National Assembly to enact laws that would make local government councils autonomous and give them powers to generate their own revenue.

“Local governments are the oldest globally accepted means through which governments impact positively on the lives of people at grassroots level, and any Bill targeted at delisting from the constitution is an abuse of democratic tenets and procedures,” he said. “Local governments must be strong, autonomous and allowed to generate their own revenue.”

Indeed, an own-source resource approach can bolster local government efforts to provide efficient and effective service delivery. For example, Nakuru, one of Kenya’s county-devolved units, in an attempt to reduce its reliance on national government, has established its own revenue agency with the ambitious aim of increasing from some $16 million to at least $26 million per annum. First, however, Nakuru county, which had been unable to meet its revenue targets, passed a law that paved the way for creating the agency to assess, collect and account for all revenues.

Local governments also need to be able to borrow to finance some of their projects, especially those requiring large capital investment. However, to be able to borrow, local governments must prove their creditworthiness and meet the requirements of the prevailing regulatory and economic environment.

In Namibia, where skills shortages have led local authorities to use consultants to prepare their financial statements, auditor general Junias Kadnjeke, who was reappointed to serve a fifth term last year, has pledged to strengthen local governments’ capacity for financial reporting. Kadnjeke made this pledge after the annual audit reports of most local authorities revealed that funds could not be accounted for, and international public sector accounting standards had not been adhered to.

Service delivery will continue to suffer if development efforts don’t support generating revenue at local levels, which is why more should be done to help local governments generate their own revenue.

One such effort is in Uganda where sustainable development NGO the Southern and Eastern Africa Trade Information and Negotiations Institute (SEATINI) and Oxfam Uganda, in collaboration with Advocacy for Research in Development, are implementing a Local Revenue Enhancement Plan (LREP) to improve equitable sub-national revenue mobilisation in the cities of Gulu and Soroti.

Speaking at a LREP event in Soroti, Jane Nalunga, the executive director of Seatini Uganda, said she believed that for local governments to successfully raise their own revenue they must pay critical attention to planning.

“We believe that local government has the capacity to generate their own revenue and reduce dependence on the central government” said Nalunga, “but I want to reiterate the importance of planning.”

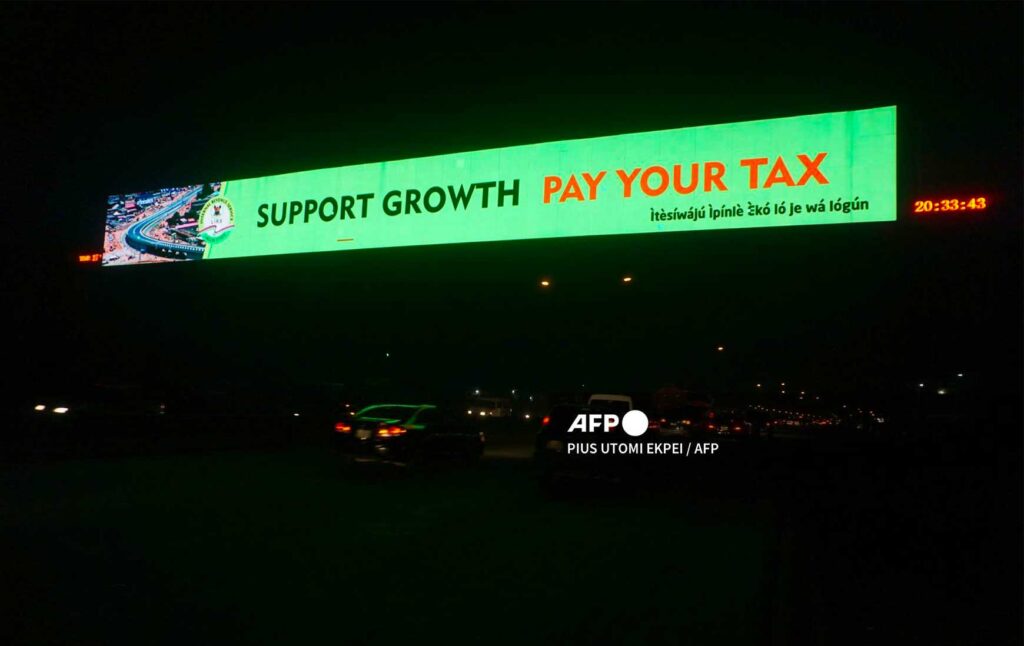

She said citizens had a role to play in being vigilant to ensure taxes collected locally were properly spent. To this end, Seatini has trained tax justice campaigners to advocate for local government accountability and lobbying fellow citizens to pay their taxes.

According to UN-Habitat, local governments have to ensure accountability to tackle a potentially serious problem in African cities, namely a growing perception among residents that the money they pay for rates and other local taxes goes into a bottomless pit with no discernible impact on the quality of physical infrastructure and services. In recent years, for example, in parts of Nairobi or Johannesburg, there have been suggestions that residents should suspend rates and service charge payments until the quality of roads, water, and sanitation begin to improve. Given the deteriorating state of infrastructure, residents will increasingly demand to see results from the rates that they pay.

In South Africa, dissatisfaction with local authorities has even seen citizens calling for some municipalities to be dissolved and put into administration. Reflecting why citizens are increasingly unhappy with local government service delivery, the SA Auditor General’s 2020-2021 report on local government audit outcomes revealed that the situation regarding financial management at most municipalities was dire, that service delivery levels and the financial health of local government had deteriorated, and was approaching system shutdown.

The African Development Bank (AfDB) has recommended in its ‘State of Urban Governance in Africa’ report, and its Strategy for Economic Governance in Africa (SEGA) 2021-2025, that civil society organisations are supported to act as effective watchdogs of public services, monitoring and evaluating public procurement to help curb corruption. In the meantime, citizens in Nairobi, Johannesburg and Lagos look for alternatives to local government services and consider their options.

Raphael Obonyo is a public policy analyst. He’s served as a consultant with the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA). An alumnus of Duke University, he has authored and co-authored numerous books, including Conversations about the Youth in Kenya (2015). He is a TEDx fellow and has won various awards.