Africa is growing exponentially, particularly in its cities and urban areas. According to the African Union, approximately 60% of Africa’s population will live in urban areas by 2030. As such, urbanisation has become a key priority for African governments. They recognise that the growth and development of these cities will shape the future of not only individual African countries but the entire continent.

However, as cities continue to grow, so do informal settlements. Informality has been a key feature of African cities since the colonial era when cities were often designed to segregate people. Thus, informality has always been understood as being separate from the process of urbanisation. This has largely informed city planning, even in the post-colonial era. More recently, scholars have been trying to reconceptualise informality not as something separate from urbanisation but as a mode of urbanisation itself.

As such, building on the work of these scholars, this article explores the issue of informality in the context of Lusophone cities. Focusing on Luanda and Maputo, it unpacks the informal settlements of these cities and highlights how governments have responded to them.

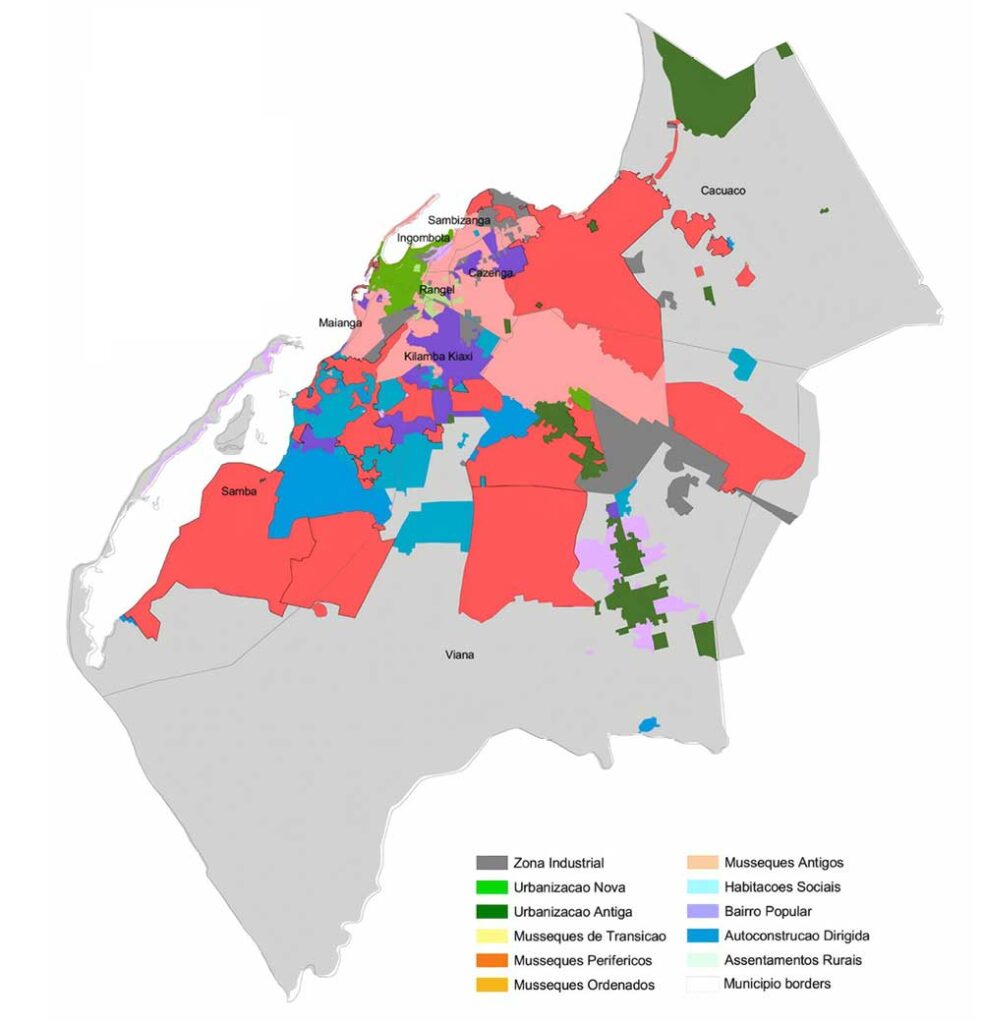

Luanda city, in Angola, is home to roughly 9.6 million people, making it the fourth-largest metropolis in Africa. Its large and rapidly growing population has resulted in a dense urban space, with housing a key issue. According to a study by researcher Allan Cain, almost two-thirds of the population live in informal settlements. Figure 1 (below) highlights the number of formal and informal settlements across Luanda Province.

Informal settlements in Luanda are known as musseques, named after the red sand on which early informal settlements were first built. There are around 65 musseques across Luanda’s urban area, which fall into four categories based on their history and development in the city. First are the “old musseques”, which were established during the colonial period, making them the first and, as the name suggests, the oldest informal settlements. Second and third are the “transitional musseques” and “ordered musseques”, which emerged much later in the late colonial and early independence periods. They are known for being situated between the different areas of Luanda’s more formal areas.

Lastly, there are the “peripheral musseques”, which are the newer settlements that emerged during the post-conflict economic boom.

These four categories of musseques are also helpful in understanding the dynamics and complexities of Luanda’s urban informality. Specifically, the old musseques tend to have more established housing and relatively better access to basic services. According to a 2019 study by Carlos Pestana Barros and Carlos Balsas, the old musseques have a lower population density than the newer ones, which have much greater population densities. This indicates that the older musseques have more established housing with some form of ownership, allowing them to gradually expand their housing over time.

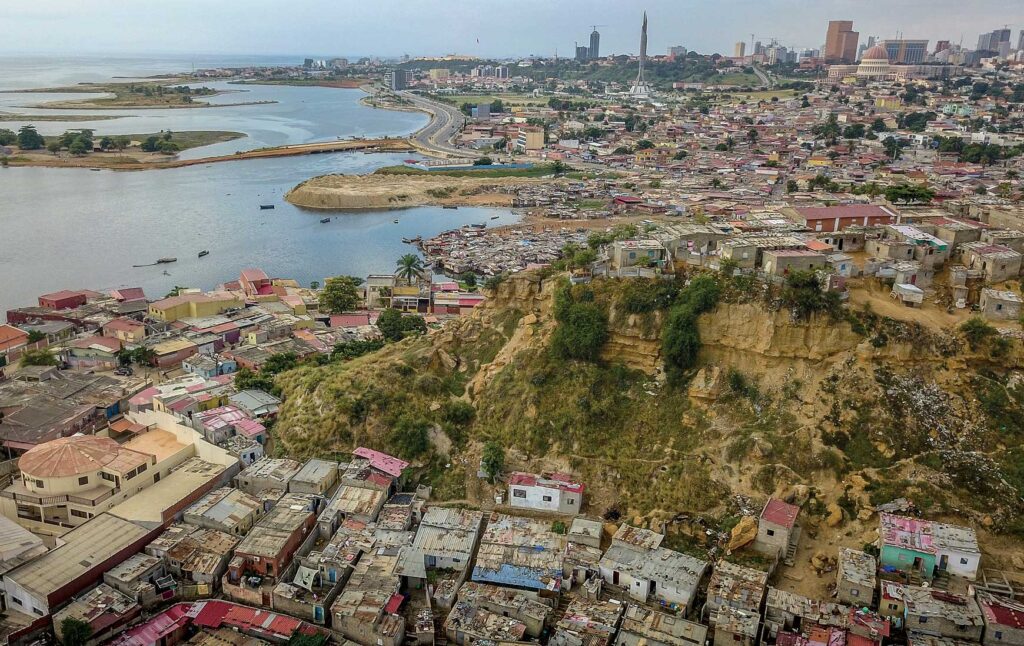

While more than 50% of housing in the musseques are made from cement, access to key infrastructure remains a challenge. This is particularly true for access to water, with the average percentage of houses with water across the 65 musseques at only 8.26%. The highest percentage of houses with water is only 30%, with these musseques some of the oldest in the city.

Another key issue is adequate housing and an effective land tenure management system. According to Jorge Manuel Gonçalves and J. M. R. F. Gama, the rapid growth of Luanda massively increased the informal settlements, with people having to live in areas prone to various environmental risks, such as flooding. This, combined with the lack of housing regulation and secure tenure for people, adds to the challenges facing Luanda’s urbanisation.

The government has attempted to address these challenges with a number of different projects. In 2009, the government implemented the National Urbanization and Housing Programme (PNUH). This was the first and most ambitious attempt to address the housing challenges and growing informal settlements. However, many of these projects under this programme resulted in some form of relocation and gentrification of musseque areas. This, in turn, has exacerbated issues around adequate housing, access to basic services and land tenure.

For example, one of the largest housing projects under the PNUH was the “Novas Centralidades” project, which aimed to build alternative housing for people on the periphery of Luanda in areas such as Kilamba-Kiaxi. However, these projects were riddled with issues, including making the houses too expensive for the poor, being overly focused on quantity as opposed to quality, and exacerbating spatial inequality.

Overall, while Luanda continues to grow at a rapid rate, the centralised government has struggled to adequately and promptly address the most pressing issues people face in the musseques. In most cases, the policies seemed largely out of touch with realities on the ground.

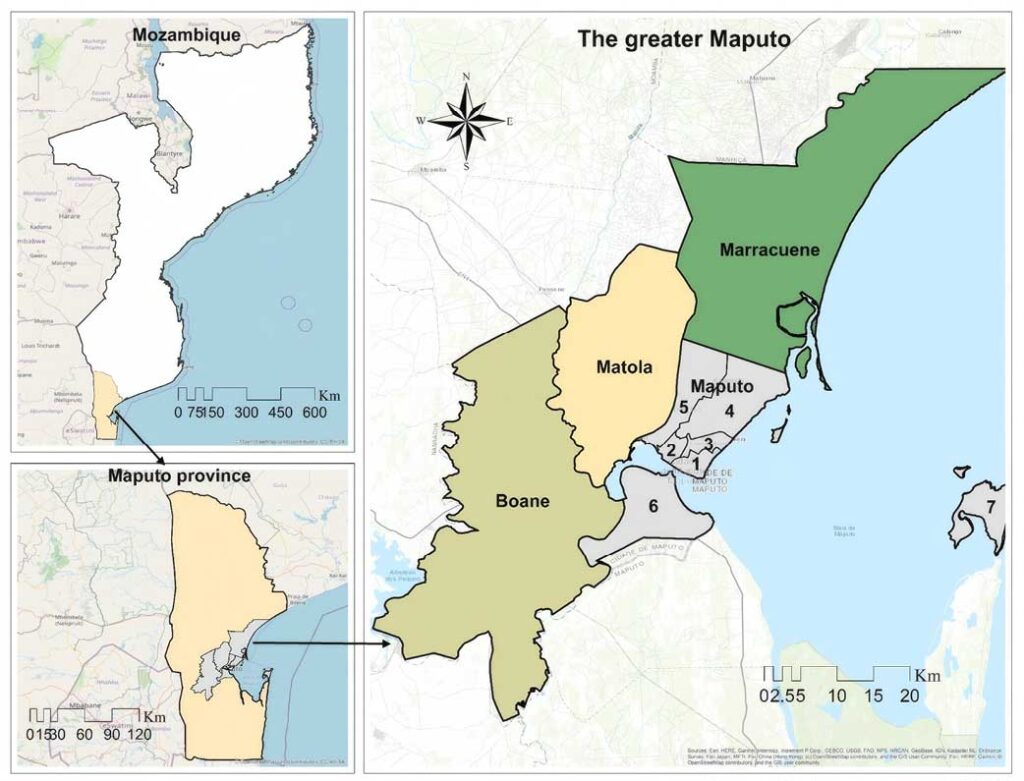

Maputo, the capital of Mozambique, is also a complex city, where the municipality only consists of one part of the wider metropolitan area. As Figure 2 shows (below), Maputo city includes a wider metropolitan area, encompassing not only the municipality of Maputo but also Matola and the districts of Boane and Marracuene.

The municipality of Maputo is further broken up into seven urban districts, including KaMpfumu, Nlhamankulu, KaMaxaquene, KaMavota, KaMubukwana, KaTembe, and KaNyaka. The entire metropolitan area has an estimated population of roughly 2.8 million people, with an average 2017 growth rate of 2.4% per annum. The number of people living in informal settlements is not fully known, with most studies putting the percentage of people living in them between 75% and 80% of the city population.

Due to the city’s colonial legacy, informality is spatial, with some areas having a higher percentage of informal housing while others have less. For example, in 2013, in Maputo, the urban district of KaMpfumu had a low percentage of informal housing at 12.6%, while KaMaxaquene had more than 80%. However, one of the difficulties in discussing urban informality in Maputo is that there is very little data on its informal settlements and the available data is outdated, which could mean these figures are much higher.

Many of the houses in these informal settlements are made of simple concrete blocks rather than materials like corrugated iron or wood. Furthermore, due to colonial and post-colonial legacies, a number of the informal settlements exist on the periphery of Maputo, and there is poor access to basic services such as water, sanitation, and solid-waste management. These issues are exacerbated by the fact that many parts of wider Maputo are vulnerable to environmental risks such as flooding.

In terms of land tenure, while all the land in Mozambique is nationalised, their land policy, Direito do Uso e Aproveitamento da Terra (DUAT), is based on a system of right to occupy and use the land. This means that while the land cannot be formally sold, its right to occupy can be transferred in exchange for money. Eleonora Dobles Perriard highlights that while this policy is recognised as one of the most progressive land policies in the world, it has been unsuccessful in practice, especially in Maputo. They note that in 2017, most households in the various informal settlements did not have a DUAT for the land they occupied. This is due to the fact that these titles are often based on political and economic dynamics, making them inaccessible to the large majority of people.

Also, the DUAT policy has struggled to incorporate the informal land market into the formal one due to poor land management practices, making it more difficult to promote the policy effectively.

To address these issues, the Maputo government took a mixed approach, using both resettlement strategies and later upgrading the current infrastructure. For example, in the 2010s, the local government, alongside the World Bank, implemented the ProMaputo project. It consisted of two phases (ProMaputo 1 and ProMaputo 2), and consisted of a number of different interventions, including promoting the DUAT system and resettling households.

However, these projects had several challenges that undermined their effectiveness. Specifically, in many cases, due to the DUAT backlog and poor management system, many resettled people did not get new areas of land to settle on and only got financially compensated. The backlog of DUATs did not address any of the challenges faced by people in informal settlements. Rather, it forced them to move elsewhere without any secure tenure, further exacerbating issues of spatial inequality.

In both case studies, the governments of Luanda and Maputo have failed to fully address the challenges of urban informality; instead, they have only temporarily addressed some of the issues. This points to the reality that, in many instances, informality itself is treated as an issue, not the issues surrounding informality, such as poor access to basic services and adequate housing.

This requires a rethinking of how informality is not only studied but addressed. In the case of Luanda, community involvement would have shown that resettlement is not an effective solution if issues around tenure are not addressed. Similarly, studies show that Maputo has poor basic service delivery, especially regarding water and waste-management systems. As such, instead of simply resettling people, one must be more critical about the actual needs of that community.

Governments need to consider down-up approaches to urbanisation policies and city planning. This should include not simply following international trends but adopting policies to address the key issues.

One way to improve policies is to prioritise data collection and management, especially in informal settlements. Data provide key and nuanced insights into people’s lived realities, but not enough effort is put into better understanding informal settlements. This undermines the ability of policymakers to make informed and data-driven decisions on how best to approach these challenges.

Ultimately, informal settlements are a key characteristic of African cities. Recognising their role within the urbanisation process can help make more meaningful and effective policies to better incorporate informal urban areas into more formal spaces.

Stuart Morrison is a Data Analyst with the Governance Insights and Analytics team at GGA. His research and expertise mainly focuses on the nexus between local governance, urbanisation and elections. He is currently completing his MA in E-science (Data Science) at the University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, with a background in Political Science, International Relations and Development studies. His multi-disciplinary approach incorporating data science and quantitative methods allows him to provide a nuanced and data-driven approach towards his research and policy work.