Mali’s risky rebel integration project

All past attempts to merge Tuareg rebel groups into the regular army have failed

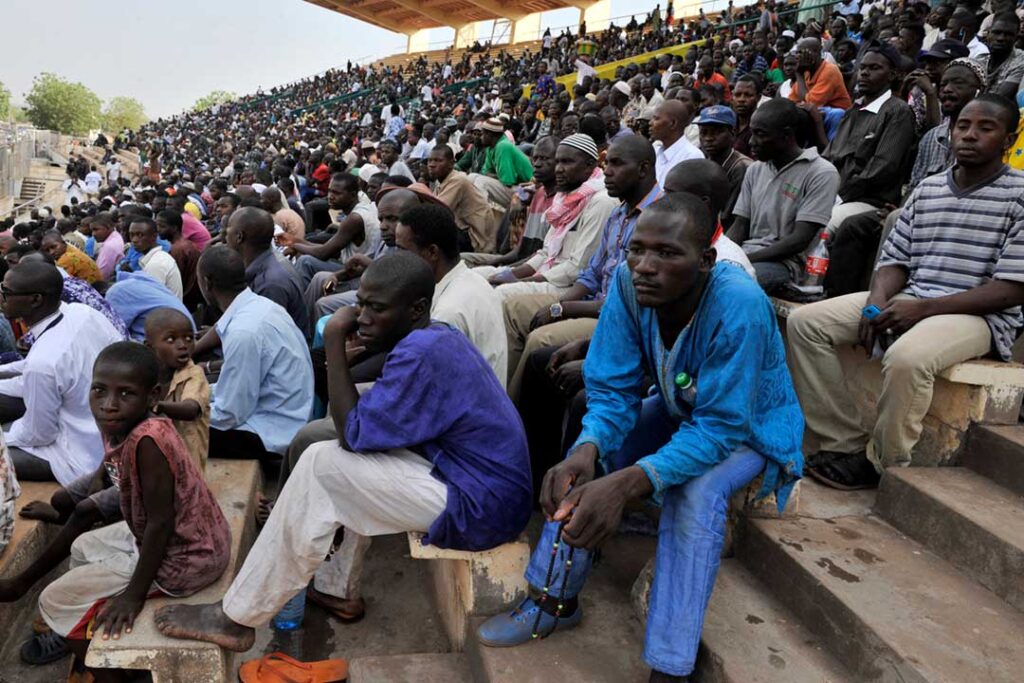

The next round of peace talks in Algeria between Mali’s government and six armed rebel groups—mostly composed of Tuaregs, the fabled blue-robed men of the desert—was scheduled for January 2015, as this magazine went to press. The third round finished inconclusively on November 27th 2014. The talks come in the wake of a Tuareg rebellion in January 2012, the fourth since Mali’s independence in 1960. The National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA), one of the groups represented in Algiers, conquered much of Mali’s northern desert, with the hope of creating an independent state to be called Azawad. The failure of the Malian army to subdue the rebels prompted a French-led military intervention in January 2013. The 2012 rebellion was based on many of the same claims as three previous Tuareg rebellions, which ended in 1964, 1995 and 2009 respectively: more authority over local government and more funding in the north for schools, roads and other infrastructure.

Although the government has often agreed to meet many of these demands since the 1960s, successive regimes in Bamako have failed to keep these promises. The demand for an independent state in 2012 was new. Tuareg attacks in early 2012 exposed two main weaknesses of the Armed Forces of Mali (FAMA): poor training and out-of-date ammunition and weapons. In contrast, the rebels proved their military strength. They had returned to Mali in 2011 after the fall of Libya’s Muammar Qaddafi, armed with sophisticated weapons and the experience to use them. By mid-2012, the FAMA had lost an estimated 1,100 soldiers against 100 for the MNLA, according to the UN. The country was thrown into further chaos when national army soldiers stormed the presidential palace in Bamako, Mali’s capital, on March 22nd 2012. This small group of soldiers ousted the president, Amadou Toumani Touré, incensed at his mismanagement of the Tuareg rebellion. The six rebel groups have tried unsuccessfully to unify their positions during the peace negotiations, which started in July 2014.

The Tuareg MNLA, the High Council for the Unity of Azawad, the Arab Movement of Azawad alongside the Co-ordination for the People of Azawad and two other dissident movements, remain divided on the issues of secession and greater autonomy. The Malian government has ruled out any talks on independence, but is open to discussions over devolving more authority over local affairs. One of the main concerns that remains on the table is a project to integrate and in some cases re-integrate about 3,000 rebel fighters into the Malian army. They are mostly northerners who fought in the 2012 rebellion, but also include about 500 Tuaregs who deserted the army between 2011 and 2012. Moussa Mara, Mali’s prime minister, first introduced this integration project in May 2013, describing it as critical to achieving national reconciliation. But some Malian authorities and military officials are worried that traitors and criminals could be joining an army they once tried to destroy.

Armed groups who occupied Mali’s north summarily executed approximately 150 Malian soldiers in 2012, according to a May 2014 report by Human Rights Watch, a New York-based advocacy group. This is not the first time the Malian government has attempted to incorporate Tuareg fighters into its army. It has tried and failed many times. The strategy has been exposed as a superficial fix that does not resolve the underlying differences that have so often turned comrades into enemies. The government first attempted to include the rebels in the regular Malian army in the 1990s—during and after the 1990-1995 rebellion. In 1993 Mali integrated 610 former Tuareg combatants into the army. Three years later it incorporated 1,200 Tuaregs into the army, national guard and gendarmerie, 300 into the police, customs, water and forestry services, with a further 120 into the civilian administration, according to FAMA’s Lieutenant-Colonel Kalifa Keita.

This re-integration process, however, was particularly painful for the Malian army, explained General Moussa Sinko Coulibaly, Mali’s interior minister from April 2012 to March 2014. “We promoted many rebels and some Tuareg officers were appointed to key government positions, which created great resentment among long-serving and highly educated soldiers,” he said. “Our soldiers accepted to work with men who had fought against them a few months earlier,” General Coulibaly said. “We made exceptional preferences to these former rebels by giving them promotions even though some of them were completely illiterate. But that was the price to pay for peace.” One former rebel, who asked to remain anonymous, agreed. “Tuaregs were the bosses of the Malian army,” he said. “We were so powerful within the army that even the thieves belonged to us! We regret what we have lost because we know we will never have it again.” Since the 1990s Tuaregs have deserted the national army, taking weapons and vehicles with them.

Most often, they join rebel movements composed of their own ethnic groups in neighbouring Algeria, Libya and Niger. The exact number of desertions over the past 20 years is not known. The latest failed attempt at rebel military integration stemmed from the July 2006 Algiers Accords, signed between Mali’s government and a Tuareg rebel group. This peace accord aimed at bringing security and economic growth to the north. As part of this agreement, the government installed special security units in the north staffed by local Tuaregs, explained General Coulibaly. This arrangement did not work, General Coulibaly admitted. Seven months later, other rebel factions, who felt excluded by the Algiers agreement, took up arms against the government. This demonstrated the deep divisions that exist among anti-government forces in Mali, further complicating any integration project. If integration is pursued, former insurgents should be spread out among different units to prevent plots against national institutions, General Coulibaly said.

If special units composed of minority ethnic groups are created, high-ranking officials from these groups could build a personal support base of armed state- and non-state actors, recreating conditions for further rebellions. Mistrust sowed in the past will make any new integration project “extremely challenging”, General Coulibaly said. “If some of these men now come to the peace talks in Algiers to discuss possibilities of reintegration, it is difficult to take them seriously.” Unfortunately Africa has very few cases of successful rebel-military integration (RMI) to inspire Mali or inform its decisions. Armed non-state actors, such as rebel movements, are fluid and often divided along ideological, language, cultural or ethnic lines. Engaging them successfully requires a flexible and context-specific approach. Over the past 20 years, Burundi, Sierra Leone and South Africa have tried incorporating former competing military forces into a single national army.

This process has rarely proved successful, particularly when countries have merged fighting forces into an already existing and often weakened national army. The failure of RMI in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) has some salutary lessons for Mali. As part of a 2009 peace accord, rebels from the National Congress for the Defence of the People (CNDP), a militia/political party, were integrated into the DRC’s national army (FARDC). But in the spring of 2012, a few defected and formed the M23, after the March 23rd 2009 signing of the peace agreement. The integration approach in the DRC failed because it mixed different ethnic groups, according to Mark Knight, a director at Montreux Solutions, a private security advisory company. “While both unit and single combatant integration took place, soldiers moved towards leaders and brigades of their own ethnicity, thus polarising the new national military (FARDC),” Mr Knight wrote in a 2011 report. “One consequence was that soldiers were reluctant to accept postings in regions where their ethnic group was not seen to be in charge.

Old rivalries from the civil war remain and have led to an escalation in tensions between different brigades.” Niger, Mali’s eastern neighbour, has successfully dealt with former rebel fighters and offers lessons for Mali. For years it integrated defecting forces back into its army. But this solution was discarded because access to weapons gave former insurgents the opportunity to rebel again. In 2006 Niger decided to include a disarmament clause in its peace deals with rebels. Since then, Niger has not incorporated rebels into its armed forces but rather into the civil service. Disarmed, Niger’s rebels have had to shift their method of struggle to constructive dialogue with the central government. Mali’s prime minister is clear that assimilating Tuareg fighters into the army must remain on the table. “Without integration, no agreement; without an agreement, no peace,” Mr Mara told Africa in Fact in October 2014. But if Mali does not learn from its own or other countries’ experiences, integration offers little hope of lasting peace. Disarmament of non-state actors will be a necessary first step towards enduring national reconciliation—whether an integration plan is agreed upon or not. Mali’s longterm peace depends on the government maintaining its monopoly of force.