Children’s rights in Africa

“Africa rising” will remain a children’s fairy tale unless governments protect the continent’s young people

Africa is the world’s youngest continent. About 40% of Africans—some 416m people—are 14 years old or younger, according to a 2012 African Development Bank report. Another 200m between the ages of 15 and 24 live on the continent, according to the OECD, a Paris-based think-tank.

These youngsters represent a potential “demographic dividend”, one of the main pillars of the optimistic “Africa rising” narrative. The demographic dividend occurs when a country reduces its fertility and child and infant mortality rates, creating a working-age population larger than the population dependent on it.

But for this narrative and its attendant blessings—a growing middle class, higher standards of living, technological innovation, etc—to be anything but a fairy tale, Africa’s young people must be protected. This evaluation shows that despite some action at policy level, in most African countries the legal framework protecting African children is as fragile as those it aims to defend.

A child is a human being below the age of 18, according to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), adopted in 1989. Children are society’s most vulnerable members. Their rights are broader than ordinary human rights and include the right to “protection and care”, which requires governments to adopt the appropriate legislative and administrative measures to secure their safety and well-being.

The Organisation of African Unity, the predecessor to today’s African Union (AU), adopted the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (ACRWC) one year after the CRC. This treaty addresses the specific realities of Africa’s children: “their socio-economic, cultural, traditional and development circumstances, natural disasters, armed conflicts, exploitation and hunger”. Together these two documents form the main legal instrument for promoting and protecting children’s rights in Africa.

The ACRWC’s preamble implicitly questions, but crucially does not forbid, certain African cultural practices that are incompatible with children’s rights. It states that “any custom, tradition, cultural or religious practice that is inconsistent” with the charter should be “discouraged”, but falls short of banning such practices.

As of last January, all 54 AU member states had signed the charter. But seven had still not ratified it: Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Western Sahara, Somalia, São Tomé and Príncipe, South Sudan and Tunisia, according to the ACRWC’s website. These countries have not ratified the treaty because their traditional laws and practices are inconsistent with the ACRWC, according to a 2009 guide published by Save the Children, an international charity.

The charter is weak and does not protect children because the AU allows governments to cherry pick the parts of the treaty that these countries wish to enforce and to ignore those which might offend some interest groups.

For instance, the charter specifies that the minimum legal age of marriage is 18. Egypt does not respect this provision in practice. While Egypt’s constitution generally prohibits underage marriage, the principles of Islamic sharia law are the source of family law for Egyptian Muslims, according to Lucy line Nkatha Murungi, head of the children and the law programme at the African Child Policy Forum, an international pressure group based in Addis Ababa.

This means that despite the AU charter and domestic law, “instances of child marriage, in as far as it can be justified under sharia law, would be allowed.”

Seventeen percent of women in Egypt aged 20 to 24 were married before the age of 18, according to a UNICEF survey updated in 2013.

Sudan also does not uphold the charter’s specified minimum legal age of marriage, nor the requirement to provide education to pregnant girls.

“A lack of effective implementation” is one of the major obstacles to promoting children’s rights in Africa, according to Divya Naidoo, a programme manager at the South African division of Save the Children. A 2014 law review completed by the Children’s Institute, a Cape Town-based research and advocacy body, showed that while laws protecting children were in place, they were often not enforced.

For example, South Africa and the ACRWC prohibit corporal punishment in schools. Despite this ban 15.8% of South African school pupils—about 2.2m children— were punished physically in 2012, according to Statistics South Africa’s General House- hold Survey.

The number of children involved in armed conflict remains a problem on the continent, despite an optional addendum to the CRC signed by 44 African states in 2002. This protocol stipulates that signatories “shall take all feasible measures to ensure that persons below the age of 18 do not take a direct part in hostilities”. While the precise number of child soldiers is contested, a 2012 Human Rights Watch report estimates that there are between 200,000 and 300,000 child soldiers worldwide, and of these, 100,000 live in Africa.

What is the use of these charters and laws? Have they improved children’s rights and ultimately their well-being? Only slightly, if one looks at the progress of the UN’s Millenium Development Goals (MDGs) between 1990 and 2012.

The statistics do not reveal any direct effect of the charter on the MDGs, but at the very least, the AU charter’s adoption signified a push towards institutionalising children’s rights on the continent.

More children are going to school. Sub-Saharan Africa’s primary school enrolment rate increased from 52.67% in 1990 to 77.2% in 2011, according to UN information.

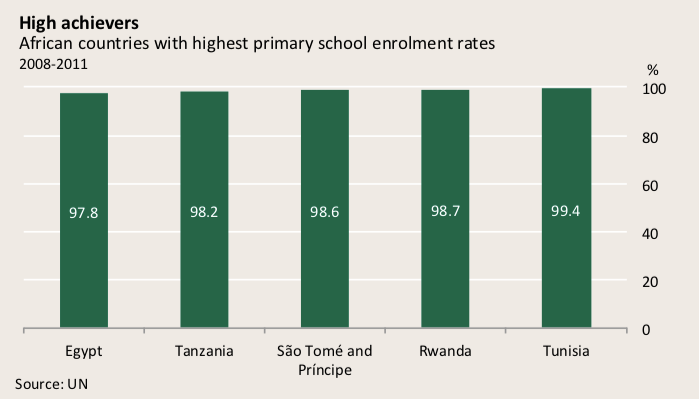

At the country level, Tunisia, Rwanda and São Tomé and Príncipe have made the greatest strides towards achieving universal primary education, with enrolment rates averaging 99.4%, 98.7% and 98.6% respectively between 2008 and 2011, according to Unicef.

Although more children are attending school, Africa still scores well below the world average. Primary school enrolment rates in sub-Saharan Africa in 2011 averaged 79% and 75% for boys and girls respectively, compared to 94% and 97% for their respective male and female peers in the East Asia Pacific region, and 95% in Central and Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States (countries that once belonged to the former Soviet Union), according to UN figures.

African infant mortality has also declined since 1990. In 2012, it averaged 79.4 deaths per 1,000 live births, down from 90.5 24 years ago, according to UN figures.

HIV/AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis continue to disproportionately affect children in Africa, particularly HIV/AIDS: 91% of the world’s HIV-positive population under 14 live in Africa, according to a joint 2013 study by the World Health Organisation, the United Nations Population Fund and the World Bank.

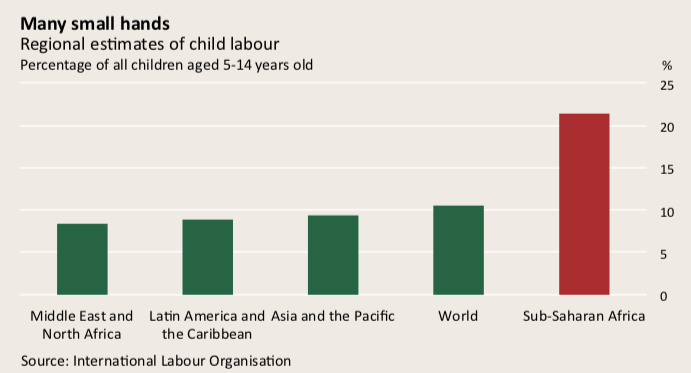

Sub-Saharan Africa has the highest rate of child labour in the world, with one in four children aged 5-17 working, according to a 2010 report by the International Labour Organisation. This is compared to one in eight in the Asia-Pacific region and one in ten in Latin America, according to the report. African children often work in mines and other hazardous sites, according Unicef’s 2011 State of the World’s Children report.

Some countries have strengthened children’s rights, showing what can be achieved when governments translate political will into action.

Rwanda, for example, has adopted several child-focused laws and policies, and established a national commission that exclusively oversees education and child protection, with special attention paid to violence, abuse and sexual exploitation. The east African nation also passed a bill of rights for children in 2012.

As a result, Rwanda has been among the continent’s top performers, along with Algeria and Tanzania, in reducing childhood hunger and mortality, maternal mortality and malaria, according to UN figures. Underweight children under five have decreased from 24.3% in 1992 to 11.4% in 2012; the mortality rates of under-five-year-olds has fallen from 150.9 per 1,000 live births in 1990 to 55 in 2012.

Botswana has also improved the welfare of its youngest by focusing on health- care. In 2001 all AU member states signed the Abuja Declaration in Nigeria’s capital and pledged to commit 15% of their national budgets to health. However in 2010 only four African countries—Botswana, Rwanda, Togo and Zambia—had honoured this commitment, according to a 2012 KPMG report. Botswana, for instance, succeeded in reducing its maternal mortality ratio from 910 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in 1990 to 160 in 2012, according to the World Bank.

Rwanda and Botswana show that the promotion of children’s rights requires political will and action, not just policies and plans. In both countries, children have not only benefited from child-focused policies, but from the countries’ broader development strategies.

Improving infrastructure, governance and haphazard laws though not specifically child-focused will nevertheless improve the lives and safety of children across the continent. Until this performance is repeated more widely across the continent, Africa’s children will remain vulnerable and “Africa rising” will remain a fairy tale.