Kenya’s beer queen

Tabitha Karanja’s success is a classic “David and Goliath” tale

Tabitha Mukami Karanja chats with her senior managers in her spacious office in Naivasha, 70km west of Kenya’s capital, Nairobi. Behind her stands a chest of drawers stacked with green and brown bottles bearing the labels of her company’s liquor brands. Against another wall is a wooden cabinet with files and several trophies.

The soft-spoken Ms Karanja, 49, is the founder and CEO of Keroche Brewer- ies, Kenya’s first locally owned beer manufacturer. Despite her calm demeanor, Ms Karanja is unrelenting in her quest to expand Keroche’s share of Kenya’s lucrative liquor trade beyond its current 5%. Her target is to command a 30% share within a decade, she says.

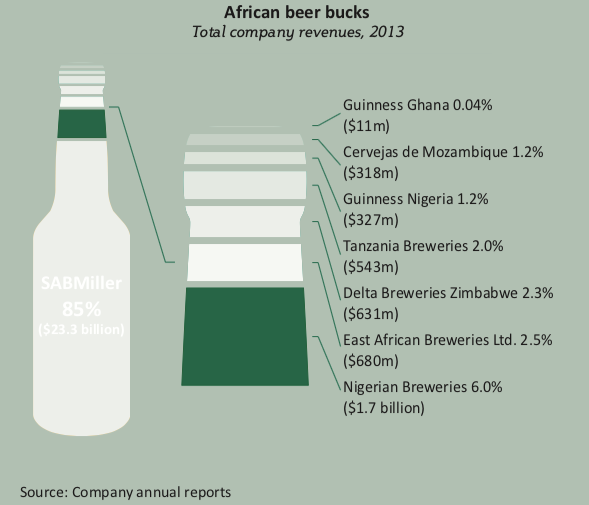

Ms Karanja’s story is a classic “David and Goliath” tale. The company, which she founded in 1989, was the first local firm to challenge East African Breweries Limited (EABL), the powerful company that has dominated the Kenyan alcohol trade for 92 years UK-based Diageo now controls EABL, which started out as Kenya Breweries, founded by the British Hurst brothers in 1922. With its flagship Tusker beer, Johnnie Walker whisky and Snapp apple flavoured alcoholic drink, EABL commands 90% of the liquor market, but Keroche is making inroads, especially outside Nairobi, where Ms Karanja markets her brands aggressively.

Ms Karanja’s story began in 1965, when she was born to middle-class parents in Kijabe, 41km west of Naivasha. She was the first of ten children, a role that prepared Ms Karanja for her future leadership responsibilities. “I played a key role in bringing up my siblings,” she boasts. “I walked from one class to another just to know how they performed.”

After finishing high school, she worked for three years as an assistant librarian in the tourism ministry. In 1987, at the age of 22, she earned a diploma in business management at the University of Nairobi. Two years later she married Joseph Karanja, who ran a hardware shop in Naivasha. Together they opened a small alcohol factory in 1992 that specialised in fortified wine—wine with an added distilled spirit, usually brandy.

When the winery started making profits, Ms Karanja stepped forward to be the face of the business, trusting her ability and resilience in the high-margin industry. She named the business Keroche in honour of her father-in-law, Karanja Mwangi, whose friends call him “Keroche”.

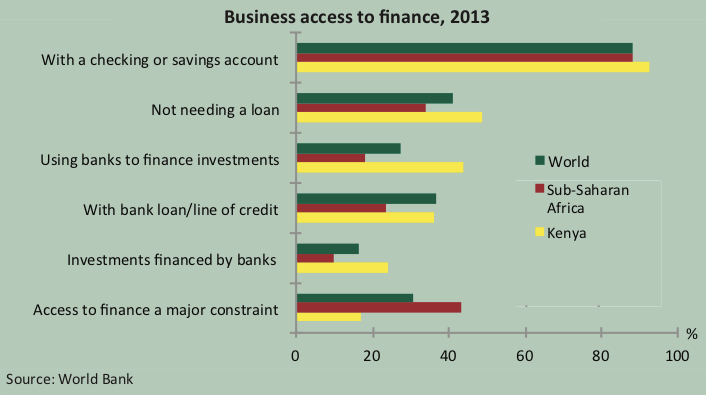

The new business faced a challenge in 1993, when banks refused to advance it capital to expand, she says. This is relatively typical in Kenya. Formal financial institutions have extended credit to fewer than 20% of small to medium-sized enterprises in the country, according to FSD Kenya, an independent trust established to support the development of financial markets.

Like many other small-business owners in her position, Ms Karanja turned to her family for help. She does not disclose the exact sum, but she speaks of having mobilised “little family resources”.

Her next challenge was exorbitant taxation. Between 1992 and 2006, Ms Karanja says, taxes on bottled alcohol products in Kenya rose by nearly 300%. This harsh taxation reduced formal alcohol consumption in Kenya from 400m litres in 1991 to 200m litres by 2006, according to an internal survey by Keroche—a situation that dried up some of the fledgling brewer’s profit margins.

Then the brewer’s Keroche and Viena fortified wines started gaining popularity in 1997 and exposed the businesswoman to further headaches: in 2003 the Kenya Revenue Authority (KRA) accused her of withholding 1 billion shillings ($11m) in taxes. Ms Karanja denied this. The stand-off dragged on until 2006, when the KRA ordered Keroche to pay up within two weeks or face closure. Ms Karanja stood firm, sued the KRA and won.

Taxes were not only too high, they were unfair, she says. In Kenya’s 2006-2007 budget, the finance minister did not levy a value-added tax on EABL’s Senator beer, but doubled the tax on fortified wines, which were Keroche’s mainstay. This made the ground uneven, Ms Karanja says.

But it was harassment by state officials, who demanded bribes of as much as 1 billion Kenyan shillings ($11m) for licences, that almost destroyed her young business, she says. She refused to pay these kickbacks.

“For more than ten years, I fought tough battles against intimidation from state officials as well as multinationals,” she says. “At times, they would shut our processing plant, but we never gave up. This is my country and I had to fight on.”

A major turning point in Keroche’s story came in February 2008, when Ms Karanja secured a 1 billion shilling ($11m) loan from Barclays Bank. She had proved her mettle as an innovator and a capable business leader and financial institutions were responsive to her credit needs. Ms Karanja used the capital injection to boost her fac- tory’s infrastructure and capacity from three small rooms with five employees to much larger premises of about 4,000 square metres and more than 100 skilled workers. In October 2008, Ms Karanja boldly entered the beer market and launched Summit lager.

Kenya is the largest beer market in east Africa, according to a 2012 report by Renaissance Capital, a Russian investment bank that tracks emerging markets. With GDP growth of 4.6% in 2012 (according to the World Bank) and a fast growing population, its market remains the region’s most robust, according to the report.

Breaking into the beer industry in Kenya has historically been difficult, even for SABMiller. The London-listed beer behemoth opened a brewing plant at Thika, about 35km north-east of Nairobi, in 2008. But after EABL mounted an aggressive advertising campaign and rolled out several cheap products to gain market advantage, SAB Miller sold its facilities to EABL in 2010.

Keroche’s Summit lager, however, succeeded. The company now sells between 4.2m and 5m bottles of the lager and malt beer per week. Its share of the Kenyan alcohol market moved from 2% in 2008 to the current 5%, according to Keroche’s own market research.

What has made the Summit beers and Keroche’s other products thrive? Analyst Paul Okinyi of Nairobi-based Baseline Consulting credits the company’s innovation, its frequent rebranding and repackaging, and its 100%

Kenyan ownership. Keroche’s motto, “Truly Kenyan”, has helped endear the company to the country’s beer consumers, he says.

Ms Karanja is convinced that her segment of Kenya’s beer market will expand to reflect the rise of the country’s economy. “As people move up the income ladder, per capita spending on beer rises significantly,” according to a 2013 report by KPMG, an advisory firm.

Her story is even more remarkable because of the patriarchal barriers that Ms Karanja sidestepped. Women hold only 12% of seats on the boards of Kenya’s top companies, according to a 2013 Kenya Institute of Management report, and only 14 of the 290 seats in Kenya’s National Assembly. Of Kenya’s 47 elected senators in the upper house, none is a woman.

Besides leading Keroche, Ms Karanja is also a senior board member of the Kenya Association of Manufacturers. In 2013 Ventures magazine rated her as one of the most powerful women to watch in the continent’s corporate sector.

Last year Keroche announced a 2.5 billion shilling ($28m) expansion plan that will see its production capacity mushroom to 600,000 bottles a day from the current 60,000 by November 2014. Keroche plans to go regional next year, expanding sales into Burundi, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda.

Ms Karanja, a mother of four, credits her success to determination. “I am what I am because of hard work,” she says. “To succeed where many failed calls for sacrifice.” She still finds time to spend with her children and her husband, now the company chairman. “We share dinners and celebrate birthdays together.”

Ms Karanja wants to make it easier for other entrepreneurs to follow in her foot- steps. She implores the Kenyan authorities to make the playing field fair. “Biased and over-taxation will destroy the industry,” she says. “We would like to see the government create a conducive business environment that emphasises fairness in word, deed and spirit. Competition is the key to innovative alternatives.”