Zimbabwe: land issues

Questions of tenure and compensation have taken centre stage in a new phase of Zimbabwe’s agricultural revolution

Zimbabwe’s agricultural and political landscape was turned upside down in 2000 when government-supported mobs chased mostly white commercial farmers from their farms. This burst the country’s main economic artery and earned President Robert Mugabe notoriety in the West.

The fever of world reaction has since died down. The attitude of the international community, for the most part, seems to be one of acceptance—at least publicly. Zimbabwe’s land revolution has now entered a new phase where legal questions of tenure and compensation have taken centre stage.

About 8m hectares of farmland owned by 3,000 white farmers in 1999 is now legally state-owned land according to the Valuation Consortium, a private, Harare-based body that has collected information from evicted white farmers and advertisements placed in the state media since 2000. Most of the “beneficiaries”, as the state lands department calls the occupiers, do not have security of tenure, legal protection afforded to tenants. This means they are either loyal to Mr Mugabe’s Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriotic Front (Zanu-PF) party or they keep their mouths shut.

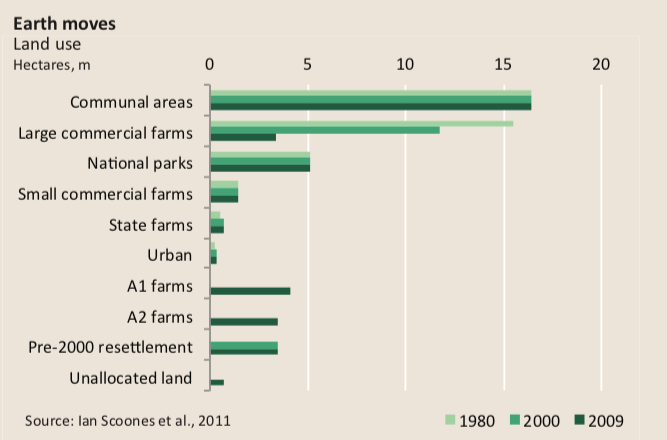

Among these new tenants are the A1’s, about 230,000 beneficiaries and their families who were allocated small pieces of white-owned farms, according to Mandivamba Rukuni, a World Bank land consultant. About 18,000 politicians, senior civil servants and their families were handed larger pieces of land. They are known as the A2’s.

The A2’s were supposed to become the new, large-scale or commercial farmers, according to the government’s fast-track land reform programme, which emerged in 2000.With no commercial farming experience or loans to finance crops and equipment, many A2’s have failed and much fertile land remains fallow.

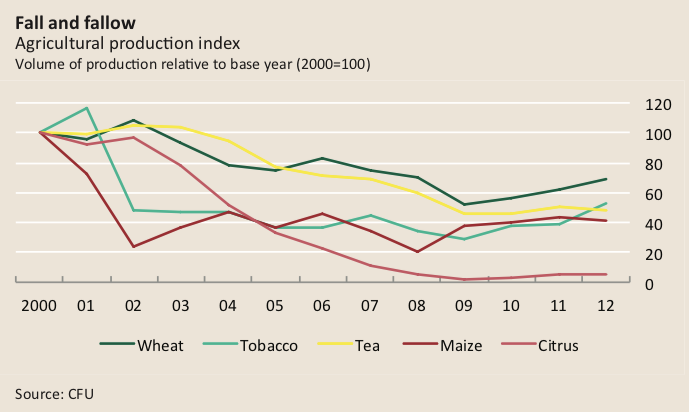

Zimbabwe’s corn crop withered in the chaos following the land invasions. In 2000 the maize yield was 2m tonnes, according to the Commercial Farmers Union (CFU). This was sufficient for human and animal consumption and occasional exports. But by 2008 this was down to 417,000 tonnes.

This year’s improved crop of about 1.4m tonnes, helped by above average rain in some areas, will likely be only enough for domestic human consumption, according to the famine early warning system funded by US Agency for International Development.

When the evictions began, Zimbabwe was the world’s second-largest tobacco exporter, producing about 200m kilograms of flue-cured Virginia tobacco annually, according to government export statistics. By 2004 this had fallen drastically to 54m tonnes, according to the CFU. By the end of last selling season in July, however, 90,000, or nearly a third, of the small-scale farmers, grew between one and two hectares of tobacco, according to Zimbabwe’s Tobacco Industry Marketing Board. Industry insiders estimate that the yield was back up to pre-invasion levels.

The Land Acquisition Act of 1990 and amendments and changes to the Zimbabwean constitution since 2000 all afford compensation to evicted white farmers for improvements on their land, such as houses, fencing and barns.

The “new” A1 and A2 farmers do not pay rent for the land they use. They cannot sell or rent it out legally until the government pays this compensation that it still owes to more than 90% of evicted white farmers.

The government has made little progress in establishing fully tradable 99-year leases for the larger pieces of land now owned by the commercial farmers—which will eventually be equivalent to title deeds, Mr Rakuni says.

Mr Mugabe said in August that 8,000 small-scale farmers would be given permits for their land by the end of the year. These permits, which are still being compiled and distributed, have not yet been tested in court to see if they provide security of tenure.

Foreign banks are reluctant to lend money to new farmers without title deeds. They have seen that the Commercial Bank of Zimbabwe lent to many larger farmers who, for the most part, failed to repay their loans, Mr Rukuni said. ”They are incompetent farmers and had no experience of how to manage a loan,” he adds.

Many smaller farmers in Zimbabwe’s tobacco-producing central provinces grow their crop with loans from foreign-owned dealers, such as Northern Tobacco, the local partner of British American Tobacco. These firms also provide technical coaching, hoping to see their loans repaid. Most get their money back, according to industry insiders.

About a dozen Zanu-PF new larger farmers are sub-letting to former owners, according to white tobacco farmers who wish to remain anonymous. The government is aware of these leases, but has not approved them, Douglas Mombeshora, lands minister, told pro-Zanu-PF newspaper The Heraldin August. The government is preparing legislation to manage the situation, he added.

White farmers complain of paying bribes, usually to a local Zanu-PF official, to continue to operate. Sometimes the bribes are paid in cash, sometimes in fuel. Other payoffs include seed, fertiliser and the use of their tractors.

The business of farming has changed dramatically since 2000, Mr Rukuni said. Zimbabwe’s farmers now face competition from across its borders. Many retailers import some vegetables and most fruit from South Africa because it is cheaper than that grown in Zimbabwe, not least because of economies of scale.

Since Zimbabwe abandoned its own currency in 2009 and adopted the US dollar, tobacco production costs have risen in in the country to about $12,000 per hectare, according to interviews in August with officials from the Zimbabwe Tobacco Association and several tobacco farmers.

As a result, even some of the most competent remaining white tobacco farmers are getting into debt. Since few still-called new farmers can afford to cure tobacco with coal, they are cutting down the forests in the country’s central, tobacco-growing regions.

So what about the national land audit agreed to by Zanu-PF and the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) ahead of the formation of the 2009 unity government—which many believed was essential to a better agricultural future?

A national land audit would turn out to be a “political audit”, as those demanding it want it to check which Zanu-PF boss took more than one piece of land, Mr Rukuni said. Zanu-PF is strong enough to ignore the calls.

Meanwhile the government should concentrate on fixing infrastructure, such as roads and electricity, necessary for agriculture, Mr Rukuni said, as well as assessing onerous tax structures and “informal taxes”, a term commonly-used for various methods of police extortion such as illegal roadblocks and other pay-offs.

The May 2013 constitution restated the government’s obligation to compensate evicted white farmers for improvements or capital assets. The Valuation Consortium has appraised most of the improvements and the land taken by the state 14 years ago.

The valuations seem reasonable, modest even, based on market prices for rural agricultural land at the time of the invasions. The older the dispossessed white farmers get, the more flexible they will be when negotiations for compensation begin.

However, the Zimbabwe government has no money to pay off its foreign debt, let alone white farmers. If it did manage to find the cash—and potential donors indicate informally that they cannot imagine more than $2 billion emerging—there would still be no chance of compensation until the UK and Mr Mugabe make peace, according to Mr Rukuni and other analysts.

Mr Mugabe wants Britain to retract a 1997 statement by the Labour government to the effect that Britain has no responsibility for Zimbabwe’s land problems. “One of the two primary reasons for the [independence war] was to return land taken by the settlers to the indigenous people, as happened in Kenya,” said Reginald Austin during an interview in August. Mr Austin was a member of the legal team for Joshua Nkomo’s Zimbabwe African Peoples’ Union (Zapu) at the 1979 negotiations at Lancaster House in London.

These negotiations broke down over the land issue. The Patriotic Front (Zapu and Zanu) was later persuaded to accept the deal, “then go home, win the election, and then, when in power, deal with the land situation”, Mr Austin added. “If the land problem had been sorted out in London at that time, it would have set land reform on a path similar to Kenya,” he said. The land issue was never formalised in the Lancaster House settlement.

Relations between Zanu-PF and Britain soured further when Tony Blair, Britain’s former prime minister, openly supported the opposition MDC in elections in the early and mid-2000s. Zanu-PF leaders publicly interpreted this as a strike against the liberation struggle and said it rekindled memories over the 1979 Lancaster House disagreements.

This means compensation will probably have to wait until Mr Mugabe, 90, and apparently fit, departs the political stage.

Many analysts say it would be too much of a political risk to pay off white farmers since they were not the only ones who lost out during Zimbabwe’s hyper-inflationary period. Teachers, nurses and other civil servants went without pay for years, and many in the private sector lost their pension funds.

The World Bank could play a role in fixing the compensation mess, according to the CFU. The Zimbabwe government could issue bonds that the World Bank could underwrite and guarantee, the CFU said. This would create a land bank for development, whose funds could be augmented by renting state farmland.

The CFU does not expect evicted farmers—many of whom have left the country—to return. It advises issuing title deeds to the new settlers. “All the benefits of secure tenure need to pass from one party to the next in order to bring closure,” the farmers association said in a 2013 strategy paper.

Meanwhile sporadic farm invasions continue, even though Mr Mombeshora and others in Zanu-PF say they are no longer policy. One invader, deputy chief secretary in the president’s office, Ray Ndhlukula, defied a high court order in August and took land from a farmer in western Zimbabwe, according to Bulawayo’s Southern Eyenewspaper. Ian Ferguson, owner of Zimbabwe’s last game farm, near Beit Bridge in the south, says he has spent the last year trying to prevent thugs from wrecking the wildlife reserve. He has provided detailed accounts and photographs of these incidents to lawyers and journalists.

These and similar attacks are “opportunistic” invasions and Zanu-PF does not authorise these takeovers, Mr Rukuni said. However if white farmers are involved, the police will usually not implement court rulings handed down in their favour, he said.

Mr Mugabe’s government is bankrupt and struggles each month to pay public sector wages, according to civil service insiders. Zimbabwe state media reports suggested that Mr Mugabe was looking for financial assistance when he paid an official visit to China in August. Independent financial analysts in Harare speculate that Mr Mugabe was looking for $4 billion as a soft loan, but that any such bailout would have to be secured by minerals or land for agricultural investment. So far only a handful of Chinese migrants to Zimbabwe have turned their hands to farming. These have been mainly private initiatives.

Meanwhile, the government needs to speed up production of tradable leases to all farmers on state land to create a climate for investment. This would include embracing, rather than punishing, the few hundred remaining white farmers.